BUSHMAN PAINTING – THE BASICS OF IMPRESSIONISM

In 1910, the artist and critic, Roger Fry, wrote a surprising essay. He claimed that paintings made by the Bushmen of of the Kalahari, though often crude, showed that they were able to paint outlines in the impressionist mode rather than in the schematic mode which more or less dominated all other cultures. Fry wrote that: “extremely complicated poses are rendered with the same ease as the more frequent profile view, and that momentary actions are treated with photographic verisimilitude.” It is a puzzle how they were able to do this.

We have been discussing the way in which European artists had engaged in a centuries-long struggle which led them away from recording concepts to tracing shapes. Fry thought that the bushmen had been able to short-circuit this arduous process of discovery, and had been able to go directly to tracing shapes. He proposed that the Bushmen’s minds might be free from the concepts which had proved such an obstacle to European artists. The Bushmen were able to observe with eyes and brains which were totally innocent, or rather, considerably less encumbered than those of Europeans. Their drawings are outlines of animals and people, shapes which have been extracted from the multiplicity of shapes which may be observed in reality. So their conceptualisation was clearly sufficiently developed to be able to separate a subject from a background.

As photographs of Bushman art show, some of the drawings are hard to discern on the stone surfaces on which they are painted, so it is helpful to see the copies with which Fry illustrates his comments. These show the essential characteristics of the drawings more clearly than the photographs do. Fry’s statement is the classic description of the eye which is largely innocent, and is best appreciated in some of his own words.

BUSHMAN PAINTINGS – AND COPIES BY MISS TONGUE

Oxford : Clarendon Press. 1909.

Oxford : Clarendon Press. 1909.

Oxford : Clarendon Press. 1909.

The drawings are of different periods, though none of them probably are of any considerable antiquity, since the habit of painting over an artist’s work when once he was forgotten obtained among the bushmen no less than with more civilised people.

BUSHMAN ANALYSIS OF MOVEMENT

In Europe, moving horses were depicted as if they were rocking-horses, until, in 1873, Eadwaerd Muybridge (1830 –1904) started to produce instantaneous photographs of moving animals. His photographs demonstrated that the rocking-horse pose was not true-to-life. As Fry pointed out, the Bushmen had already made accurate observations of animals in movement, using only their eyes.

Most curious of all are the cases of which Fig. 4 is an example, of animals trotting, in which the gesture is seen by us to be true only because our slow and imperfect vision has been helped out by the instantaneous photograph. Fifty years ago (i.e, in 1860) we should have rejected such a rendering as absurd ; we now know it to be a correct statement of one movement in the action of trotting.

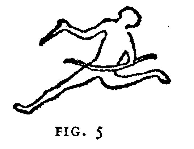

Or again, the man running in Fig. 5. Here is the silhouette of a most complicated gesture with foreshortening of one thigh and crossing of the arm holding the bow over the torso, rendered with apparent certainty and striking verisimilitude.

ANCIENT GREEK SCHEMATIC – BUSHMAN IMPRESSIONISTIC

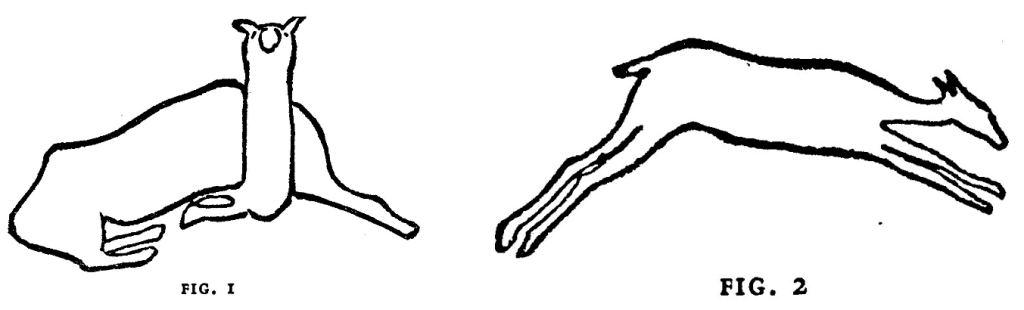

A rhebok seen from behind in a most difficult and complicated attitude. The drawing depends far more on the visual impression than on classification of the parts.

Another surprising instance of this is shown in Fig. 3, taken from Plate XIX of Miss Tongue’s book, and giving a rhebok seen from behind in a most difficult and complicated attitude.

An example, of an animal trotting, in which the gesture is seen by us to be true only because our slow and imperfect vision has been helped out by the instantaneous photograph. The bushmen made observations which were far more accurate than those made by Europeans.

Found near the Dipylon, the main gate in the city wall of Classical Athens.

The Greek illustration was taken from the Dipylon Amphora (a type of container with a pointed bottom), a large Ancient Greek painted vase, made around 750 BC, and now in the National Archaeological Museum, Athens. Painted amphorae of this size were made as grave markers.

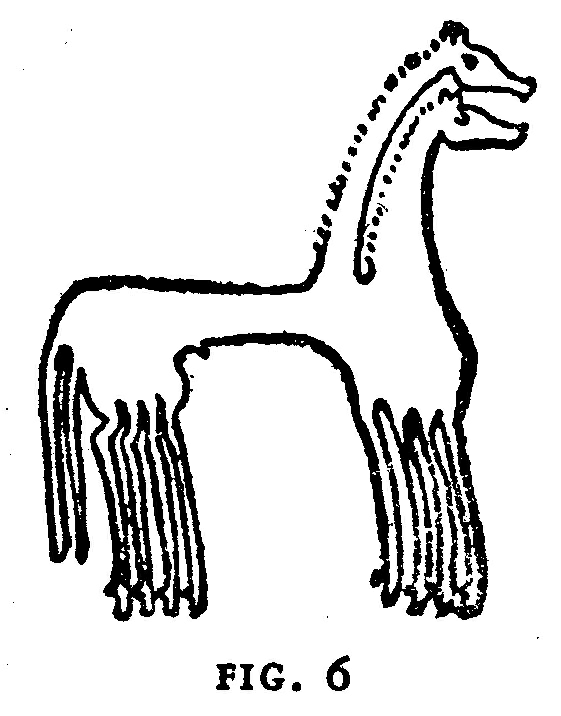

By way of contrast to these extraordinary performances of the Bushman draughtsman, I give in outline, Fig. 6, the two horses of a chariot on an early (Dipylon) Greek vase. The man who drew it was incomparably more of an artist ; but how entirely his intellectual and conceptual way of handling phenomena has obscured his vision ! His two horses are a sum of concept-symbols, arranged with great orderliness and with a decorative feeling, but without any sort of likeness to appearance. Mr. Balfour, in his preface to Miss Tongue’s book, notices briefly some of these striking characteristics of the Bushman drawings. He says : —

ALTIMERA c.10,000 BC

Since, then, Bushman drawing has little analogy to the primitive art of our own races, to what can we relate it ? The Bushmen of Australia have apparently something of the same power of transcribing pure visual images, but the most striking case is that of Palaeolithic man. In the caves of the Dordogne and of Altamira in Spain, Palaeolithic man has left paintings which date from about 10,000 B.C., in which, as far as mere naturalism of representation of animals goes, he has surpassed anything that not only our own primitive peoples, but even the most accomplished animal draughtsmen have ever achieved.

Fig. 7 shows in outline a bison from Altamira. The certainty and completeness of the pose, the perfect rhythm and the astonishing verisimilitude of the movement are evident even in this. The Altamira drawings show a much higher level of accomplishment than those of the Bushmen, but the general likeness is so great as to have suggested the idea that the Bushmen are descendants of Palaeolithic man who have remained at the same rudimentary stage as regards the other arts of life, and have retained something of their unique power of visual transcription.

More recent studies of the paleolithic paintings have suggested that some of them may represent carcasses rather than live animals. The position of the so-called ‘roaring bull’ which Fry illustrated, may be the result of placing the body on the ground. The position of the hooves is certainly more characteristic of an animal which has been laid out, than one which is standing. Supposing the animal were observed in this way, the artist would still have had to transfer the tracing, or the memory of a tracing on to the cave wall.

IMPRESSIONISM : BUSHMAN – JAPANESE – EUROPEAN

Like Japanese drawings, they show an alertness to accept the silhouette as a single whole instead of reconstructing it from separately apprehended parts. It is partly due to Japanese influence that our own Impressionists have made an attempt to get back to that ultra-primitive directness of vision. Indeed they deliberately sought to de-conceptualize art. The artist of to-day has therefore to some extent a choice before him of whether he will think form like the early artists of European races or merely see it like the Bushmen. Whichever his choice, the study of these drawings can hardly fail to be of profound interest. The Bushmen paintings on the walls of caves and sheltered rocks are fast disappearing…

(Roger Fry was writing in 1910, over a century ago, and even less now remains).