MOST CULTURES ARE QUITE HAPPY WITH SCHEMATIC REPRESENTATIONS

Giorgio Vasari (1511 – 1574) was an Italian painter, architect, writer, and historian, best known for his Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects, considered the ideological foundation of art-historical writing.

Natural or realistic depiction does not crop up frequently over the centuries. Why did it develop at all? The art historian E H Gombrich suggested one possible reason in a brief essay: ‘Visual discovery through art’, Arts Magazine, November 1965 – reprinted in Psychology and the Visual Arts, ed. James Hogg 1969. Here are some excerpts:

And yet there remains a question which Vasari failed to ask because he took the answer for granted. If only the tricks of naturalistic painting result in convincing images that make for effortless recognition, how can we explain the fact that most cultures are quite happy with schematic representations ?

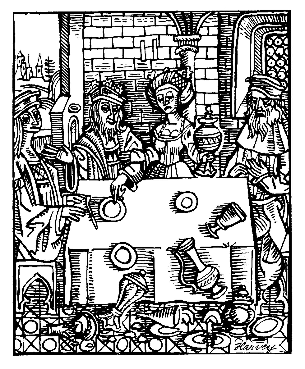

A humorous contemporary drawing, done in a medieval schematic style, which an unknown reader of my book kindly sent me from Australia, not only poses this question afresh, but may also contain the germ of an answer (Plate 16). The caption tells us (as the King watches with exasperation while his meal slides from the table to the ground): ‘It’s the way they drew these wretched tables.’

To us, at least, the medieval convention suggests in fact that the table is tilted and that nothing could stand on it. If we could find out when this feeling first arose and when this kind of criticism would have been understood, we would be a long way nearer an explanation of why artists felt that the schema was in need of correction. Once this process was set in motion, the rest may have been a matter of trial and error, of taking thought and trying again. Ce n’est que le premier pas qui coûte. (It is only the first step that costs : only the beginning is difficult ).

In my book I have tried to sketch an answer to this question as far as the beginnings of the Greek revolution are concerned. I shall try here to apply it briefly to the Renaissance, leaving it to another occasion to fill in the outlines. My answer was that the purpose of art that led to the discovery of illusionistic devices was not so much a general desire to imitate nature as a specific demand for the plausible narration of sacred events.

Perhaps we should still distinguish here between various forms of pictorial narration. One may be called the pictographic method. Here the sacred event is told in clear and simple hieroglyphs which make us understand rather than visualize it. Within the context of such a style, it may be argued, the ‘conceptual method’ of drawing a table surface produces no discomfort. The hieratic figures of the Three Angels represented on the Romanesque tapestry as partaking of Abraham’s meal (Plate 20) may look pictographic to our eyes, but the scene as such is impressive in its solemn consistency. It is only where the artist aims more visibly at telling us not only what happened but how it happened that the conceptual method becomes vulnerable to criticism.

The rise of naturalism, in other words, presupposes a shift in the beholder’s expectations and demands. The public asks the artist to present the sacred event on an imaginary stage as it might have looked to an eyewitness. There is some evidence, I think, that this demand was in fact insistent around the time of Giotto’s revolution. It is, of course, generally agreed that Giotto in his Biblical narratives aimed at such a dramatic evocation. We know that at first the effect of his art was stunned surprise at the degree of lifelikeness the master’s brush could achieve. But if I am right, it was this very success that made certain remaining inconsistencies in the spatial framework of his narratives more obtrusive. In front of his rendering of the Feast of Herod (Plate 21), an irreverent wit might easily have asked whether the dishes were safe on that table. I do not know whether such a joke was cracked, nor even whether such criticism of Giotto’s method was in fact voiced. But, clearly, the invention of perspective three generations later eliminated this potential discomfort. Its rapid spread throughout Europe suggests at least that it met an existing demand. The closer the code came to the evocation of a familiar reality the more easily could the faithful contemplate the re-enactment of the story and identify the participants.

Here the scene is set fairly realistically, but the perspective is not quite correct. The items on the table look a little as if they might fall off. This problem was overcome when the rules of accurate perspective were fully discovered 75 years later.

It is true that if this was the purpose it soon became overlaid by technical interest. The rendering of depth, of light, of texture and facial expression was singled out for praise by the connoisseur, and the problems of the craft became aims in themselves. But these aims, to repeat, were only achieved by a long process of trial and error that was guided by the critical scrutiny of paintings that failed to pass the ‘recognition test’. The motive force we may imagine as underlying the growth of naturalism is not the wish to imitate natural appearances as such, but to avoid and counter the critic’s impatient questions:’ What does this onlooker feel ?’; ‘What sort of fabric is his cloak?’; ‘Why does he throw no shadow?’

Once we describe the rise of naturalism in terms of such scrutiny, it also becomes clear that there are rival functions of the image which do not elicit this kind of question at all. Even within the context of a sacred art, it may be didactic clarity that is demanded of artists designing images that should above all be as legible from afar as are Byzantine mosaics.

Today there are such functions of the image as advertising (favoring some ‘striking’ effect) or diagrams and pictographic roadsigns (Figure 1) which are better served by a reduction of naturalistic information. Accordingly, the poster and the pictographic illustration have gradually ‘ evolved’ away from nineteenth-century illusionism.

This schematic representation is easier to understand than one which was naturalistic.

This is not as easy to understand as the schematic picture above.

I think that in strictly definable contexts such as these, the term ‘evolution’ is more than a loose metaphor. Indeed, the schematic process I have sketched out here could be presented in almost Darwinian terms. The fitting of form to function follows a process of trial and error, of mutation and the survival of the fittest. Once the standard of either clear or convincing images has been set, those not conforming will be eliminated by social pressure.

Gombrich was discussing the path which led from drawing symbols to duplicating the image-in-the-viewfinder. He suggested that the first step along this path may have been taken when viewers began to be dissatisfied with pictures which simply told a story, and demanded that pictures should be closer to what an eye-witness would have seen on the spot. This led to an interest in the skill of the artist in generating such eye-witness scenes, rather than simply in telling a story. This was most likely how the idea of Fine Art developed, as the skill in depiction became at least as interesting to the viewer as the story itself. The treatment became more interesting than the subject.