Kenneth Clark’s description of Renoir’s return to the classical style illustrates the central importance of the viewer’s response in defining the classical style.

By relying more on this change from warm to cool than other painters, the Venetians were able to make their areas of tone flatter and simpler.

Venetian colour is not stronger or brighter than that of other painters, but it is more controlled in warm and cool contrast. This provides not only a richer sense of colour, but a more true-to-life appearance.

Nude (Anna)

1876

Oil on canvas, 92 x 73 cm

Pushkin Museum, Moscow

The warm colour of the skin becomes cooler (greyer or even bluer) in parts where the body turns away from the light slightly, only to become warmer (browner) in the darkest parts.

Clark refered to this painting as Anna in Moscow because that is where the painting now hangs.

Before the Bath (Avant le bain)

c. 1875. Oil on canvas

Barnes Collection

I was not able to find a painting in the Barnes Collection which was from this period of Renoir’s life and also called ‘torso’. This may be the one which Clark referred to. It exhibits the same sensitivity to warm and cool as the Anna in Moscow (above).

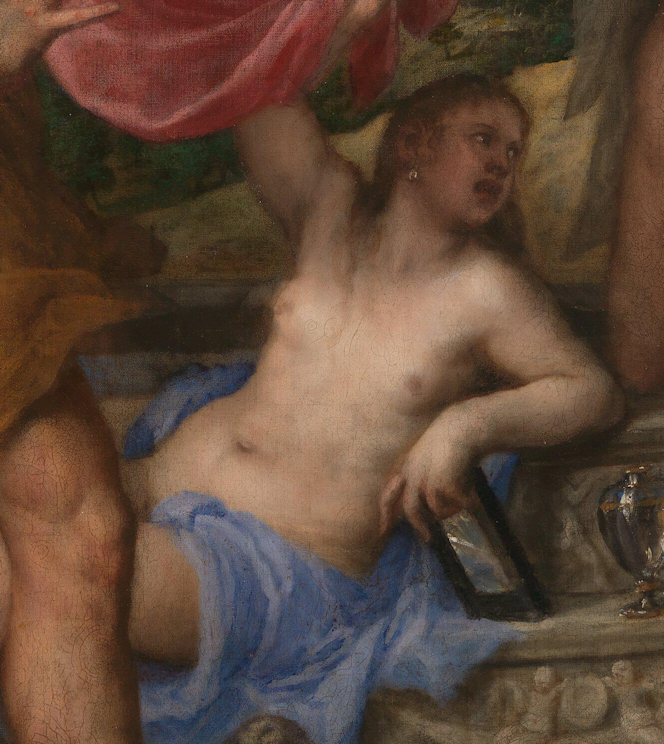

Detail from Diana and Acteon 1556-9

The change of colour on the skin from warm to cool (skin colour to greyer skin colour) is characteristic of Venetian painting, and also of Renoir’s paintings above.

Clark wrote of Renoir:

…his instinctive understanding of the European tradition showed him how the great Venetians had rendered form through colour and he painted two nudes, the Anna in Moscow and the Torso in the Barnes Collection, which might almost be details from Titian’s Diana and Actaeon.

*Here Clark alludes to the geometrical solids which form the basis of classical drawing – usually referred to as cylinder, sphere and cone.

In these the outline is minimised by overlapping forms and by the broken tones of the background, but the modelling is solid, and there seems to be no reason why Renoir should not have continued to paint a series of masterpieces in this manner. However, it did not satisfy his conviction that the nude must be simple and sculptural, like a column or an egg*, and by 1881, when he had exhausted the possibilities of Impressionism, he began to look for an example on which such a conception of the nude would be based. He found it in Raphael’s frescoes in the Farnesina and in the antique decorations from Pompeii and Herculaneum.

The Nude – A Study of Ideal Art, Kenneth Clark (1956)

The Triumph of Galatea c. 1512

Fresco

Villa Farnesina, Rome

This painting exemplifies the clarity and ease of outline which so impressed Renoir.

Here again is the clear outline. Even though the figures look solid there is little emphasis on separate muscles, which might tend to split up the figures, thus there is the feeling that each figure is one piece, moving wih ease and dignity – a quality which impressed Renoir.

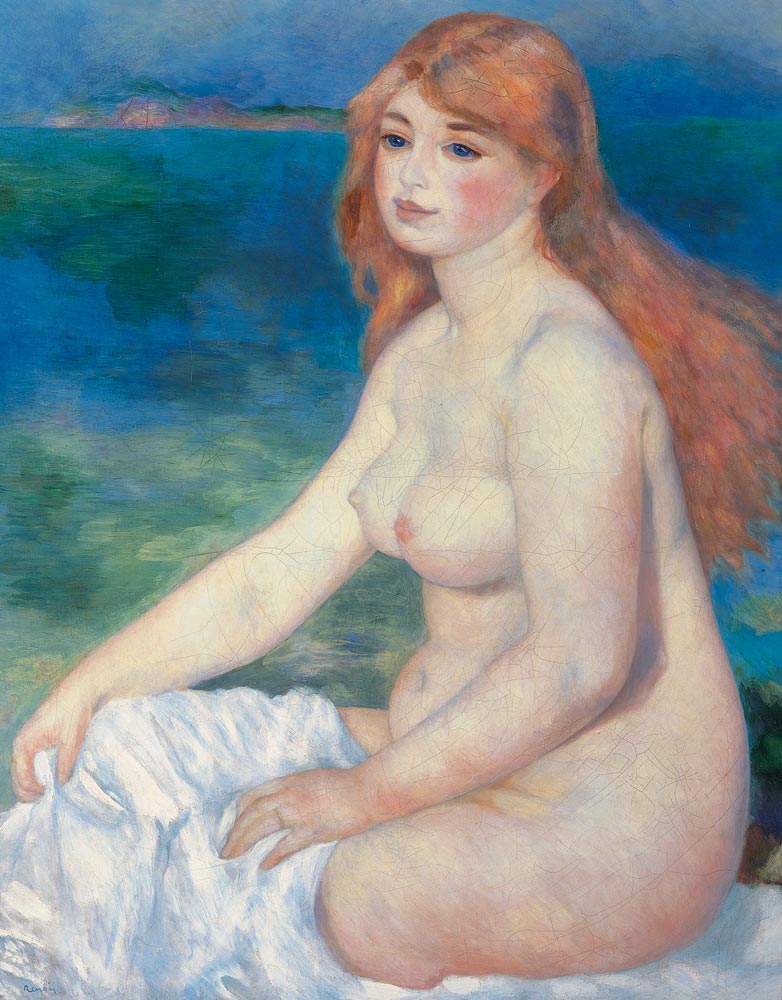

La Baigneuse blonde, oil on canvas, 90 x 63 cm,

Pinacoteca Agnelli,

Turin

The painting in which Renoir clarified the outline, while keeping the delicate sense of warm and cool colour that he had developed when working in the Impressionist manner.

The immediate result was a picture of his wife known as the Baigneuse blonde, painted at Sorrento towards the end of the year, in which her body, pale and simple as a pearl, stands out against her apricot hair and the dark Mediterranean sea as firmly as in a painting of antiquity.

The Nude – A Study of Ideal Art, Kenneth Clark (1956)

Venus Anadyomene (Venus rising from the sea) c. 1520

Oil on canvas 75.8 cm × 57.6 cm (29.8 in × 22.7 in)

Scottish National Gallery, Edinburgh

Ancient Greek: Ἀφροδίτη Ἀναδυομένη; ἀναδυομένη, anadyoménē, meaning “rising up”;

Clark wrote that this picture, like Renoir’s, ‘gives us the illusion that we are looking through some magic glass at one of the lost masterpieces extolled by Pliny…’

The Ludovisi Cnidian Aphrodite,

Roman marble copy (torso and thighs) with restored head, arms, legs and drapery support

4th century BC

The Aphrodite of Knidos was made for the Temple of Aphrodite (Venus) at Knidos or Cnidus, a city of Greek colonists in ancient Caria …now part of modern-day Turkey.

The original statue has been lost, so it is known only through the many copies, all slightly different.

Some artists have considered the proportions of this statue to be ideal; but, as Clark pointed out, Renoir’s painting gives the viewer a classical feeling, even though Mme. Renoir’s proportions are very different.

Like Raphael’s Galatea and Titian’s Venus Anadyomene, the Baigneuse blonde gives us the illusion that we are looking through some magic glass at one of the lost masterpieces extolled by Pliny, and we realise once more that classicism is not achieved by following rules—for young Madame Renoir’s measurements are far removed from those of the Cnidian—but by acceptance of the physical life as capable of its own tranquil nobility.

The Nude – A Study of Ideal Art, Kenneth Clark (1956)

NB: “… realise once more that classicism is not achieved by following rules...”

So the classical style is not a matter of applying a rigid formula, but of combining schemata which give a feeling of perfection. This sense of perfection is not unique to Greece and Europe. Artists from other parts of the world have also met the requirements which were set out by classical authors and by B. R. Haydon, even if their pictures represent people who are clearly not ancient Greeks.

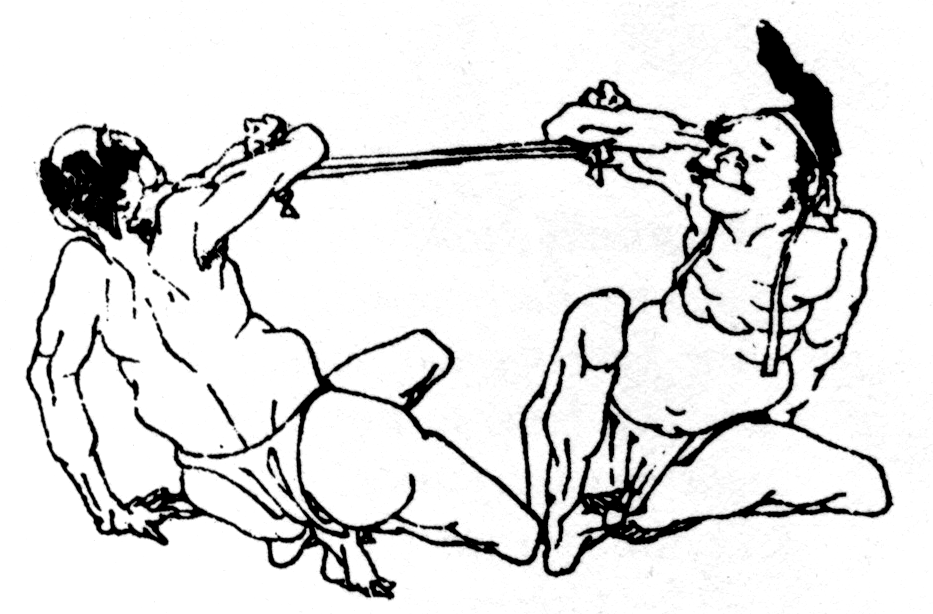

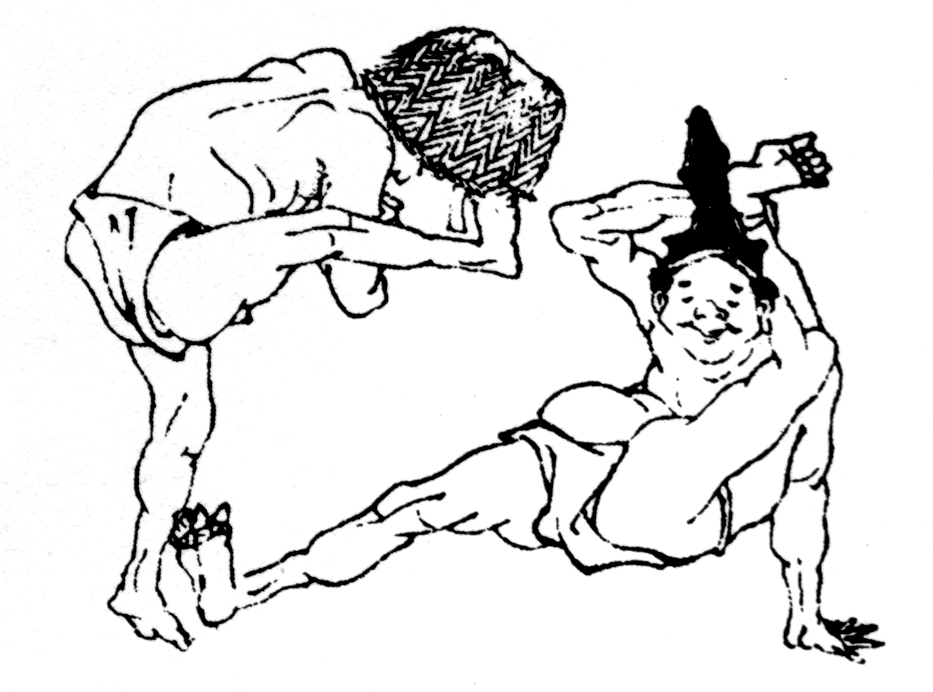

Paintings on the walls of the Ajanta caves (second century BC and later) in India and the drawings of Hokusai (1760-1849) in Japan also demonstrate characteristics of the classical style. It seems that the so-called ‘classical’ volumes of cylinder, sphere and cone (and also the cube and cuboid) are inherent in the human mind – so that they appear everywhere that representation is taken to any degree of sophistication. They underlie the unembellished outlines of Hokusai as much as the more fully drawn out volumes of Raphael.

These painting share much with the paintings of Pompeii in the simplicity of outline and grace of movement.

Painted about 2,000 years ago. It is still possible to discern the elegant shapes and the clear, but natural disposition of the figures.

Peddlers in Snow, from Vol. 3 of the book Hokusai gafu (An Album of Pictures by Hokusai)

-Boston Museum of Fine Arts

https://collections.mfa.org/search/objects/*/hokusai

Figures wrestling – 01

Reproduced in Principles of Figure Drawing (1948), Alexander Dobkin (1908-1975)

Figures wrestling – 02

Reproduced in Principles of Figure Drawing (1948), Alexander Dobkin (1908-1975)

Figures exercising

Reproduced in Principles of Figure Drawing (1948), Alexander Dobkin (1908-1975)

In Figure Drawing 1948, Rowland Alston (1895-1958) compared the ideals of beauty (p82):

1. as Plato thought of them: simple geometrical lines, shapes and solids

2. as Reynolds thought of them, close to an average of a given group of similar objects – the average of a group of faces, for example. It is what Kant called correctness. This is the way in which psychologists determine beauty, by measuring human response. (Relatively recent studies have shown that the ideal is slightly different from the average, even though close to it).