A PERFECT RECORD OF THE PICTURE PLANE OFTEN LOOKS FALSE

Some photographers have valued a sense of falseness, a sense of the photograph showing you more than you noticed at the time you pressed the shutter-release. A photograph is bound to have this effect to some extent, but many photographers select scenes on purpose in order to make this effect very noticeable.

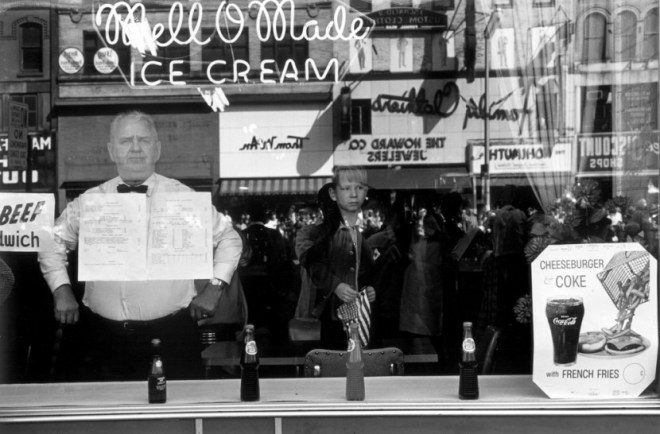

New York City, 1963

(Image courtesy Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco)

Figures cut off in a way that happens frequently, but is rarely noticed in real life because the brain looks for recognisable objects and people, thinking of them as whole, not cut off.

1960s

Appropriately set up, the photographic camera is able to ensure that all objects appear in sharp focus, whatever their distance from the lens. This can give effects which could not be seen by the eye, because the eye changes focus almost instantly when moving from a near object to a far one.

I only wanted Uncle Vern standing by his new car (a Hudson) on a clear day. I got him and the car. I also got a bit of Aunt Mary’s laundry, and Beau Jack, the dog, peeing on a fence, and a row of potted tuberous begonias on the porch and 78 trees and a million pebbles in the driveway and more. It’s a generous medium, photography.

Lee Friedlander (1934 – )

This remark is often quoted, but I have not been able to find the source.

This odd appearance, static and harsh, is almost inevitable when photographs are technically accurate (also known as scientifically accurate). There are several reasons for this.

A scientifically accurate photograph enables the viewer to inspect the subject with a thoroughness that is quite impossible in normal vision. This is why aerial photographs are taken after bombarding a city. An observer looking out of an aeroplane is a very poor witness as to the exact nature and extent of the damage that has been inflicted. He or she can observe much more back at home, inspecting the photograph.

You may like to try a simple experiment, perhaps easier to carry out now than ever – with the ubiquity of mobile telephone cameras. Stand near a crowd of people and photograph it. Close your eyes and recall the scene. Then look at the photograph you have just taken. All sorts of details will be apparent in the photograph which you did not notice in reality, but at the same time, faces and other features which struck you in reality will hardly appear in the photographs, or, when they do, will have an emphasis altogether different from what you observed with your own eyes.

from Gombrich, Art and Illusion

This is just part of the problem which arises if one attempts to paint what one really sees, (or rather, really notices). In the previous chapter we saw how a child’s copy of a Constable landscape showed what she had noticed, but her copy broke the rules of perspective, rules which Constable understood and followed. The child’s drawing could be amended to be made closer to Constable’s original, but then it would be less accurate as a record of what she had noticed and thought important.

As soon as photography was invented, viewers began to notice details in photographs which they would not have noticed in real life – very much as Friedlander explained (above). One or two painters, such as Degas, began to incorporate this sort of effect in their paintings. Some photographers attempted to go in the opposite direction, and reduce this sense of falseness. They subdued those parts of the photograph which they considered were too eye-catching.

Place de la Concorde, 1875

Degas sometimes made use of unexpected cropping (notably of the figure at the far left) that had not often been shown in paintings before the invention of photography.

There are several ways in which to achieve this end. For example, by using a wide aperture, the photographer can make the background blurred but keep nearer objects sharply focussed. Other manipulations, carried out in the darkroom, or on the computer, can lighten or darken selected areas or make them blurred. One by one these manipulations can remove aspects of a photograph which look false.

EMERSON’S DEFINITION OF NATURALISTIC PHOTOGRAPHY

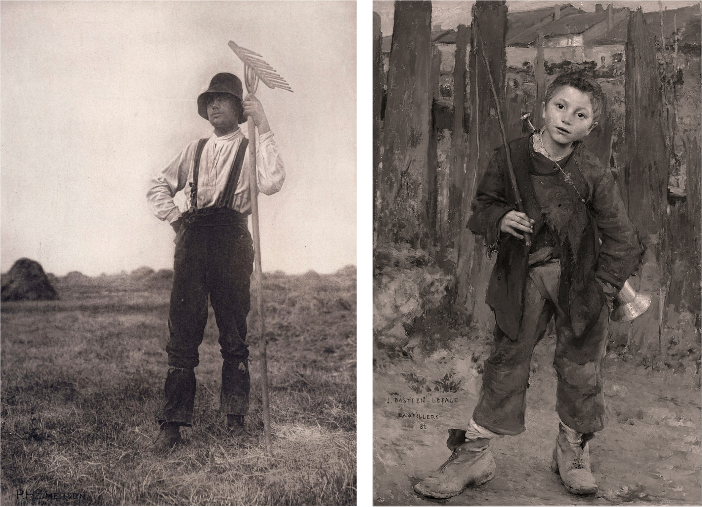

(They are shown together here for comparison, and below in higher resolution.)

Haymaker with rake, 1890 Photograph

Emerson chose an aperture which would make the background more blurred than the foreground, and he made the whole image slightly blurred (in keeping with his idea of truth to vision).

Pas Mèche (Nothing Doing) 1882 Painting

Bastien-Lepage painted in tonal areas which make the picture look very like a photograph. (The painting is shown here in monochrome in order to facilitate comparison with Emerson’s photograph).

Bastien-Lepage has used rough brushwork to make some areas less defined, similar to photographic blurring. But he has made some edges sharp, both in the foreground and in the background. A painter has greater control of emphasis than a naturalistic photographer.

Photographer and theorist.

The most fully worked-out statement about what constituted a natural appearance in photography was made by a young British writer and photographer, Peter Henry Emerson (1856 – 1936). His writing was so powerful that his views are still widely repeated, over a century later. He claimed that photography should be considered as an art equal to that of painting. His reasons still find much support among today’s photographers, but Emerson’s thinking soon developed further, and he rejected his own claim completely. The reasons why he changed his mind are just as applicable today as when he gave them. Arguments about the art of photography have not changed since those days. Emerson had said all that there was to be said on the subject.

REQUIREMENTS OF NATURALISTIC PHOTOGRAPHY

Even though Emerson reassessed his opinion on the value of photography as an art, his description of what constituted Naturalistic photography remains a helpful guide to some aspects of pictorial representation. In 1889 Emerson published Naturalistic Photography for Students of the Art. He explained his thoughts about the art of painting, and about how he believed that it could be equalled by a certain kind of photography. Emerson was convinced that photography was capable of being a major art form and not only a means of mechanical reproduction.

He defined the characteristics of a Naturalistic Photograph as follows:

__________________

Autumn

A photograph made by pasting several photographs together – a practice which P. H. Emerson considered was not true to Nature..

http://historyinphotos.blogspot.com/2013/03/henry-peach-robinson.html

1. Subject shown as it is. For example, a naturalistic landscape photographer would not add a tree, say, because he thought it would improve the composition. Emerson rejected the work of photographers such as Henry Peach Robinson (above) who had sought to imitate painting by cutting and pasting several photographs together.

2. Slight blur. An accurate, sharp photograph is held to be true ‘scientifically’, but a photograph which is true ‘artistically’ does not record details which the eye would not notice when on the spot. However a photograph should not be excessively blurred. ‘Fuzziness’ was as false as excessive sharpness.

This slight blur may vary across the picture. For example a peasant close to the viewer may appear sharper than the landscape beyond.

3. Contrast should not be exaggerated. The tonal values must be as correct as possible. P. H. Emerson recognised that the dynamic range of a painting was not large enough to reproduce all the tones of nature (white paper cannot be as bright as the sun reflected in sparkling water, for example), so the photographer would have to make a decision about which tones to show correctly. Emerson preferred the dark tones to be reproduced as accurately as possible, while “the lights could look after themselves”.

The Hireling Shepherd 1851

Here Holman Hunt exaggerated the strength of the local colours, such as the greens of the grass. Emerson considered that this was untrue to vision.

Bridge at Hampton Court 1874

Sisley painted greens which were a closer match to reality than Holman Hunt’s were.

4. Local colour should not be exaggerated. Emerson deplored the work of the Pre-Raphaelites which had exaggerated the strength of local colours, thus destroying any sense of atmosphere. In the Holman Hunt (above), for example, the greens are of extraordinary power, unlike the more accurate colours in the Sisley, which also depicts a sunny day.

____________________

In seeking truth to nature, or rather truth to eyesight, Emerson was stepping away from objective accuracy. A photograph may be evaluated objectively: for example by checking whether its values are correct, and whether the detail is sharp and accurate. Two viewers would always be able to agree on whether or not an photograph was as true as possible (within technical limitations).

But, with the concept of truth to eyesight, Emerson was introducing an element of subjectivity. For example, two viewers would not always be able to agree on how sharp an image should appear.

Naturalistic photography, as Emerson described it, had much in common with the works of the French Impressionists of the 1870s, painted a couple of decades before he was writing. Unlike Emerson, the Impressionists had colour at their disposal, and more precise control of the degree of blur; but the naturalistic photographer and the impressionist painter shared similar aims. They both replicated the image in the viewfinder as accurately as possible, consistent with not allowing details to obtrude any more than they would have done on the spot.

Note: The French Impressionists of the 1870s included much more subtle adjustments than are possible in photography – including the delineation of certain shapes. (See the Pissarro below). This introduced an element of schematisation, which is impossible in photography.

However, certain problems arose. For example, when looking at a scene through a viewfinder the observer does not see blurred areas. If the observer looks at the subject in the foreground, it looks sharp; but when looking at a tree in the distance, the eyes accommodate, and that looks sharp too. The naturalistic photograph, in contrast, is not sharp all over. In that sense it is false.

Also, what catches the eye of one person may not catch the eye of another. So the naturalistic photographer was replacing an impartial record with one that had been doctored according to personal opinion. Photography was becoming more like painting.

Blackshore, River Blythe, Suffolk

from Emerson’s illustrated book ‘Pictures of East Anglian Life’, 1888

A photograph in which Emerson demonstrated his idea of Naturalistic Photography through the subtle use of blurring.

Fox Hill, Upper Norwood 1870

This has much in common with naturalistic photography, except that the shapes and tones are controlled more precisely.

The strokes of paint which delineate the figures show direction thus indicating a schematic analysis which would be impossible in a photograph.

The same is true of many parts of the painting, the tree and windows, for example. Throughout there is a selection of shape and grouping of tonal values which is outside the range of photography.

May in the Marsh

A painting by an exponent of the Impressionist style. The impressionist style, being so close to the image in the viewfinder, has been remarkably persistent over 150 years, with few variations.

Emerson gave a brief history of art in which he evaluated all types of achievement according to his criterion – that the highest artistic goal was to be ‘true to nature’. For him, the perfect work of painting would be a slightly blurred duplicate of the image in the view-finder. Emerson found all previous artists wanting, of all countries, and of all traditions. He also described a great variety of artistic techniques, from pencil drawing, to etching, to painting in monochrome, finding them all defective when compared with photography. The only quality which photography lacked at that time was colour, though, by 1898, a practical technique for colour photography did become available.

Here are some quotations from P. H. Emerson. The opinions he expressed remain persuasive for many self-proclaimed ‘fine art’ photographers, though Emerson himself renounced all these opinions within a year. (I have added my comments as footnotes to each section.)

Photography, in fact, stands at the top of the tone class of methods of expression ; so nearly perfect is its technique that in some respects it may be compared with the colour class.[2]

[2] Emerson had reviewed all the classes of graphic work including painting in colour. By Emerson’s criterion, photography was superior to this in tonal quality, even though photography could not reproduce colour at that time.

We have, then nothing to do with “fuzziness” unless by the term is meant that broad and ample generalization of detail, so necessary to artistic work.

[3] White paper is much duller than a bright white sky, for example.

It is false in light so far as all art is false in light,[3] but photography can make more subtle distinctions in the scale than any other known black and white method.

Photography is not literal, as the flexible technique shows ; it is capable of selection almost to any extent, though, of course, it is incapable of leaving out a tree, and putting in an imaginary man.[4]

[4] Henry Peach Robinson, amongst others, had indeed combined and retouched photographs in order to achieve just such results, but Emerson regarded these manipulations as being untrue to Nature, or to human eyesight.

On the contrary, the artist, using photography as a medium, chooses his subject, selects his details, generalizes the whole in the way we have shown [5], and thus gives his view of nature.

[5] The naturalistic photographer ‘generalises’ by introducing a slight blur.

Of course, the ordinary art-craftsman has no individuality, any more than the reproducer of an architectural or mechanical drawing. But where an artist, uses photography to interpret nature, his work will always have individuality, and the strength of the individuality will, of course, vary in proportion to his capacity.[6]

[6] Emerson talked about ‘individuality’ although the crucial distinction is that between the drawing of a line and the duplication of what appears in the viewfinder.

Paintings may be much admired, even though experts cannot agree on who painted them. Questions may arise such as: “Was this painted by Rembrandt or by an assistant?” The individuality of the artist does not show beyond dispute, and yet the painting may still be highly valued.

The painter learns his technique in order to speak, and as more than one painter has told us, ” painting is a mental process,” and as for the technique they could almost do that with their feet. So with photography, speaking artistically of it, it is a very severe mental process, and taxes all the artist’s energies even after he has mastered his technique.[7]

[7] The viewer is not concerned with how hard the artist or the photographer has taxed his brain, but with what can be seen in the end product. However carefully the scene may have been selected or arranged, a photograph is duplicate of the image in the viewfinder – not an independent construction.

As we pointed out in Book I., it is our opinion that all the best art has been done direct from nature, and that no ” intention ” requires expression. No artist worthy of the name ever drew a picture evolved from his inner consciousness ; if it is a brief note to see how a thing will come ; it is either from nature, or from his remembrance of nature.[8]

[8] A child’s scribble is as much a work of art as a drawing by the greatest master. Both evolve from inner consciousness, totally independent of ‘nature’ although nature may well have entered their inner consciousnesses.

Here, then, we must leave photography at the head of the methods for interpreting nature in monochrome, and we feel sure that any one who comes to the study of photography with a rational and an unbiassed mind will admit there is no case to be made out against it as a means of artistic expression.[9]

[9] Photography is the most accurate means by which to record the image-in-the-viewfinder, but ‘artistic expression’ is made by drawing of lines, and their extensions into form, tone, and colour. At this stage, Emerson did not recognise the distinction. When he did, it hit him like a bombshell.