INVENTING VERSUS RECORDING

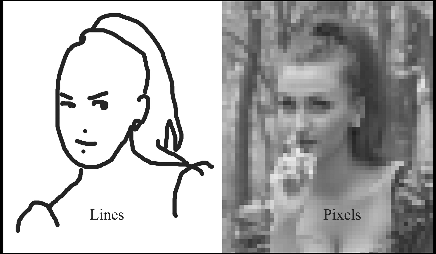

The differences between a drawing and a photograph have already been described. But the more these are scrutinised, the more profound they seem to be. Even in an apparently very objective painting, the artist demonstrates considerable invention in making shapes and colours which correspond with reality.

Pencil and brushes are tools which act as extensions of the mind. They enable the painter to make marks where he or she pleases. In contrast, the camera does not respond to thought in this way – any more than a thermometer responds to a doctor’s thought when he places the instrument in the mouth of a patient. The camera is a recording device not a tool. Those who argue that the camera is a tool like pencils and brushes have misunderstood its function.

Many famous photographers have understood this very well. We saw that Edward Weston, one of America’s most revered photographers, declared that, “The camera should be used for a recording of life”.

The only way in which a photographer can do more than make a recording is by falsifying the photograph – effectively by painting on it.

CONSTRUCTING A REPRESENTATION

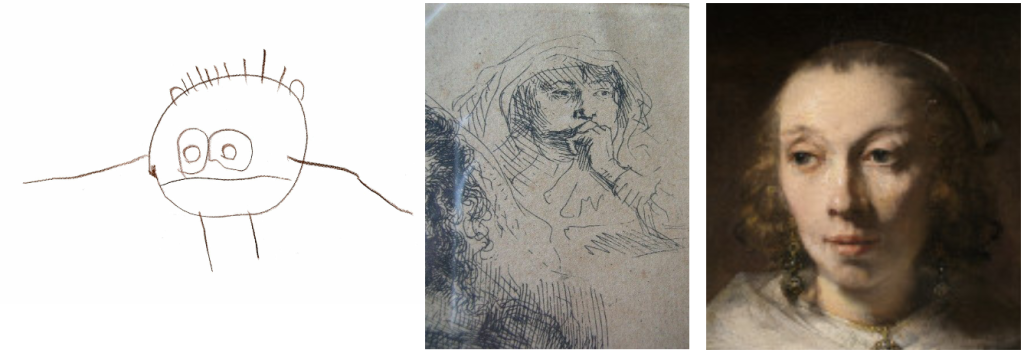

Many viewers can see that a child’s drawing is a construction, not a mirror of nature, but this is less obvious the more developed and finished the work becomes. The illustration above shows how a Rembrandt portrait, which may be considered to be photographic, nevertheless depends on such independent construction, not on recording what appears in a viewfinder. Observations are recorded using lines, along with their extensions: brushstrokes and patches of colour.

The following illustrations show how artists group tones (which are effectively extensions of lines), thus indicating that their work is a construction, or invention, rather than a record of the scene.

GROUPING TONES

Details from the book Painting a Portrait by Philip de Laszlo 1934

The subject of the portrait is the actress Gwen Ffrangcon-Davies.

(Note: The photographer was evidently slightly to the left of de Laszlo, so the views are not taken from exactly the same viewpoint.)

The photograph is as objectively accurate as possible but does not show what the photographer was thinking, other than that he aimed the camera at Miss Ffrangcon-Davies’ face.

In contrast, every brushstroke in the painting shows de Laszlo’s thinking, his selection and analysis of the face. There is no equivalent to this in photography. The value of the photograph is that it is a near-perfect record of the scene. But the value of the painting is that it shows the workings of the artist’s mind – how he responded to the scene.

Not everyone can recognise this sort of contribution from the artist, as the following story illustrates.

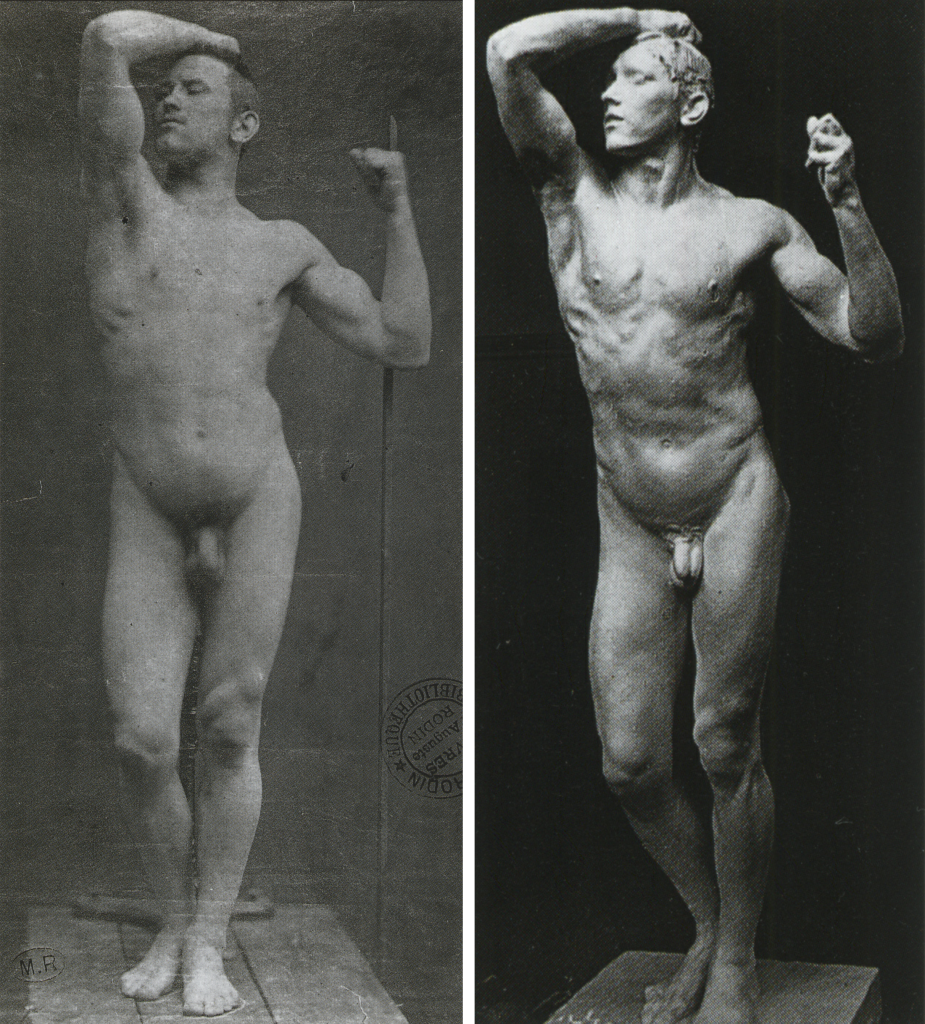

RODIN – THE AGE OF BRONZE – COPY OR INVENTION

The Age of Bronze 1877 (Seen from the back)

Left: a photograph of the model

Right: the clay sculpture before it was cast in bronze

The Age of Bronze 1877 (Seen from the front)

Left: a photograph of the model

Right: the clay sculpture before it was cast in bronze

RODIN ACCUSED

Gilles Néret

On his return from Italy, where he had seen the great works of the Renaissance, Rodin began The Age of Bronze (1875-76). This was first exhibited in Belgium under the title The Vanquished, or The Wounded Soldier. The work was apparently intended to commemorate the French defeat of 1870 at the hands of the Prussians. The following year, at the Paris Salon, the statue was greeted with the mixture of admiration and outrage elicited by so many of Rodin’s works. Compared to the cold, banal academies which were the rule, Rodin’s work was so lifelike that he was accused of having moulded it directly on the body of his model. To refute the allegation, and show how far his work was from a sterile copy, he had photographs taken of his model, a Belgian sapper named Auguste Neyt, in the same position as the statue. His efforts were in vain. His good faith was recognised only after his better-known colleagues had signed a petition in his favour. The affair had, however, made Rodin’s name, and The Age of Bronze was bought by the French state for 2,200 francs, the cost of the casting…

‘Auguste Rodin: Sculptures and Drawings’ 1994

This incident illustrates how difficult it is to make many viewers appreciate the difference between a life-cast and a naturalistic sculpture. The same may be said for a photograph and a naturalistic painting. Unless spectators can recognise this distinction, it will be impossible for them to see how inventive an artist has been.

It is essential to see what Rodin has done, the distortions and exaggerations he has made. Rodin supplied the photographs so that the viewer could spot the difference between the model and the sculpture. A viewer who has spent time looking at sculptures attentively will find it easy to recognise and appreciate such distortions, and will not need the help of comparative photographs in order to notice the distortions, but they can be a great help to others, especially beginners.

Most people can see immediately what a caricaturist has invented, whether or not there is a photograph of the original model beside it. A viewer does not have to be very sensitive to see that a caricature is not a photograph. It may take more sensitivity on the part of the viewer to see that a naturalistic painting is not a photograph, or that a sculpture is not a life-cast. A little practice is required, but the enhanced appreciation of what the artist has done will be ample reward for the effort.

This emphasises a point that Sir Joshua Reynolds hinted at in Discourse 13, that the better the art, the less likely it is to be appreciated by someone whose thoughts are directed by, “…narrow, vulgar, untaught, or rather ill-taught, reason,…” Reynolds was warning against a prejudice in favour of overly photographic works, but by the time Rodin was working, an opposite prejudice had arisen, that a realistic appearance was automatically bad. This belief is equally far from ‘well-taught reason’. The remedy is for viewers to develop a greater appreciation of what art can offer. This can come about only as the result of much practice in comparing and contrasting all sorts of paintings and sculptures. This presupposes art-lovers who are prepared to look and to ask questions, rather than simply to hope that a work will speak to them.