Sir Joshua Reynolds (1723-1792) said that the painter can capture the imagination of the art-lover in two ways:

- Superiority of subject (possible for photographers, particularly if they are not averse to manipulating the photograph).

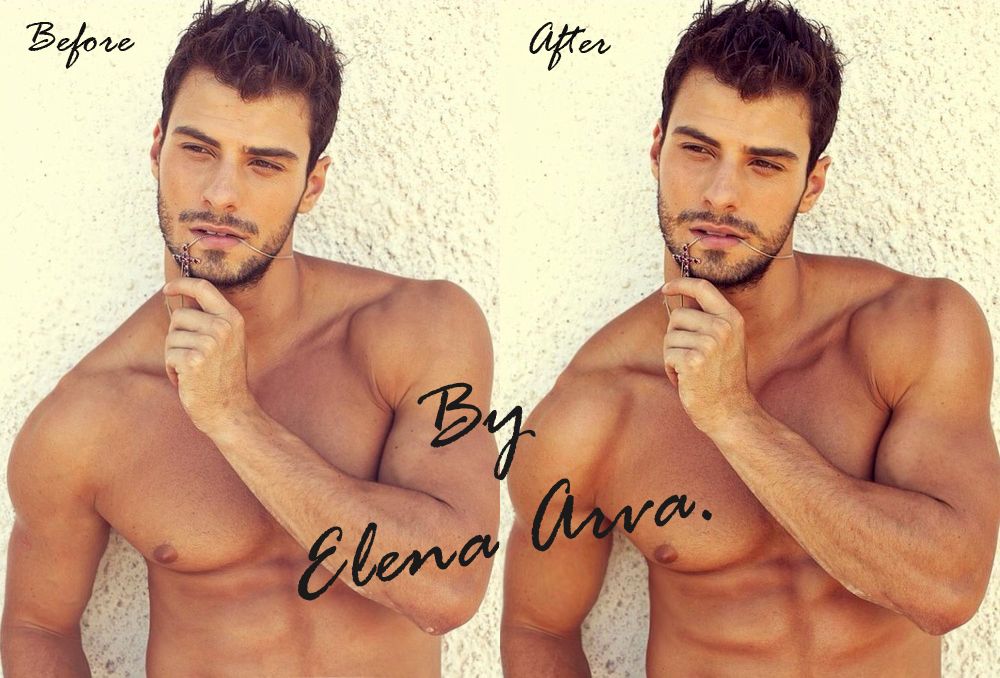

The choice of subject and what they do with it, is something which painters share with photographers. For example, a photographer may distort, say, a photo of an athlete and make his muscles bigger.

https://www.pinterest.co.uk/elenaarva/photoshop-by-elena-arva/

With the aid of computers, photographers can change not only the shape of the model, but the colouring and even the lighting (to an extent). The nearer the original photograph to the ideal (whatever that may be), the easier it is to make convincing adjustments.

https://www.pinterest.co.uk/elenaarva/photoshop-by-elena-arva/

Fashion photographers often have very strict specifications for the appearance of the models that they choose. Only a few potential models are considered to be sufficiently beautiful or striking. Women who possess these exceptional qualities can become famous, as did the Greek model, Phryne, in classical times, (though the classical ideal of beauty differed from that of today’s fashion industry).

Cnidus Aphrodite,

or Aphrodite of Knidos.

Marble, Roman copy after a Greek original of the 4th century BC.

The model for this sculpture is often thought to have been a courtesan called Phryne (born c. 371 BC).

It is the first nude statue of a woman from ancient Greece.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Phryne

2. Superiority of treatment.

A painter represents the scene by making an equivalent combination of shapes and colours. These are independent of the scene. They act as something which, like the hobby-horse, is a substitute for the real thing (or for something imaginary). This is mainly achieved by:

A: making the parts. (Line form tone colour)

B: grouping and selecting, in a word, controlling emphasis.

There is no way in which a photographer can make the parts, let alone combine them in striking ways.

The question for the viewer is : are the parts satisfactory from an aesthetic point of view (do you want to keep looking at them), and does the combination clarify the structure, or make it more interesting.

In painting, subject and treatment are usually entwined inextricably.

ADJUSTING THE SUBJECT – NOT ITS REPRESENTATION

New York : E. & H. T. Anthony & Co., 1880.

Originally published without author’s name under the title: Concise instructions in the art of retouching, London, 1876.

This shows photographic retouching from a text-book of 1876. The retouching here is concerned entirely with adjusting the subject. The intention here is to produce a photograph which looks as if it were a perfectly accurate record of a subject whose skin was smoother, and whose eyes were brighter than they were in reality. Also the lighting has been changed very slightly by lightening the area under the chin and in one or two other places. Even though the retouching was done on the negative, the effect is as if the photographer had changed the subject, then photographed it. The photograph remains a record – albeit one which has been falsified. Despite the skill which has been demonstrated, the resulting work does not show human thought, in fact it is deliberately constructed in order to conceal human intervention.

MICHELANGELO – PAINTING AS A SUBSTITUTE FOR PHOTOGRAPHING A SCULPTURE

When Michelangelo was commissioned to paint the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel he complained that he was a sculptor, not a painter (even though he had already completed at least one masterpiece in painting). In order to make his task more congenial he designed the ceiling so that it was covered with fake architectural features, including fictive niches in which it appeared that sculptures could be installed. Michelangelo filled these niches with paintings which looked like sculptures.

One might argue that, if Michelangelo had had the time and materials, he might have made sculptures instead of paintings. With modern means, he could then have photographed the sculptures and covered the ceiling with photographs instead of paintings. In fact, with modern software, he could have gone a step further. He could have made the sculptures virtually – on the computer – and then printed screen-shots of his virtual sculptures.

The result would have been be a pure photograph of a completely imaginary scene.

That photograph would include no representation, no translation of the scene into lines, shapes and colours. It would be a perfect record of what had appeared in the viewfinder, if the sculpture had actually been made. The virtual sculptures would have been constructions from Michelangelo’s mind just as much as real sculptures would have been. They would have distorted reality in just the same way. The viewer would become more aware of the masses and volumes with which Michelangelo had worked, and the rhythmic relationship between them. However, photographs of these inventions would just as empty of thought as any other photographs.

As the comparison above shows, despite his declared intention, Michelangelo’s paintings do not look like photographs of sculptures. One reason for this is the obvious one; that he has drawn lines around the figure. The modelling within the figure, too, has clarified the construction, and made the painting more informative than a photograph of a sculpture would have been.

In a child’s drawing, the subject is reduced to the simplest lines, while in those of a more advanced artist, the subject is reduced to forms such as the egg shapes of Raphael, or the box shapes of Rembrandt. These eggs and blocks are themselves ideals of a kind – ideals of perfect geometrical solids, adapted to the depiction of real figures. Even the primordial circle, which features so often in children’s drawings, is an ideal of this kind.

Thus a drawing is itself a kind of idealisation.

The word ‘idealisatioin’ is also used in another sense, as when an artist adjusts a figure in order to bring it closer to a standard, such as the proportions of a Greek stature. Both senses incorporate the idea of representation. Firstly as combinations of a vocabulary of form, such as cylinders, spheres and cones, and secondly as a vocabulary made up of ready-made, established combinations and proportions of these forms.

It could be said that all drawing depends on ideals, but that ‘idealisation’ depends on ideals which form a larger and more closely defined vocabulary. For example:

1. A figure may be drawn from a selection of solids.

2. A figure my be drawn from a selection of figures made from those solids.

Artists of the 18th and early 19th centuries felt that is was important for artists to idealise in both senses, as one can see from the lectures of Reynolds, Barry, Fuseli and Opie. In fact, these artists did not make a firm distinction between these types of idealisation.

A drawing might be considered to be ‘incorrect’, if it

1. Did not match the subject. (Simple accuracy).

2. Did not transform the subject into simple volumes. (Clarity of conceptual vocabulary).

3. Did not match the ideal forms of classical sculpture, or a modern adaptation of these ideals. (Match proportions considered to be beautiful, or striking in some sense).It would always be thought better to make an good accurate drawing of an inferior subject than a poor one of an ideal subject.

This emphasis on the ideal figure seems quite foreign to today’s thinking, even though it persists in fashion magazines. Photographs of fashion models are tweaked and retouched so that they conform to the ideal of the day, or depart from it in a way which is eye-catching and intriguing.

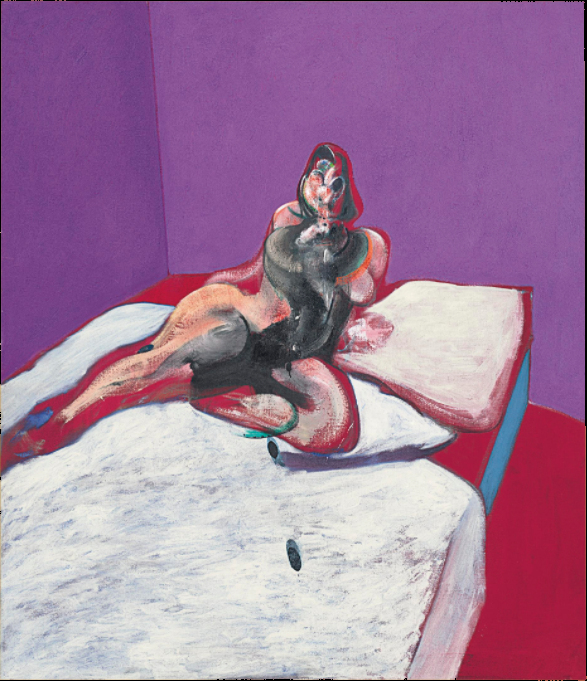

Lovers of fine art tend to consider such obsessions as being beyond the pale of art, and yet much of the fame of, say, Lucien Freud and Francis Bacon depends on the grossness of their subject matter. (Which is not to say whether the pictures are painted well or badly).

So although critics no longer hold that a subject must be ‘superior’, in Reynolds’ sense, they still feel that the subject should be striking, regardless of the way in which the artist has treated it. Ugliness is attractive to people bored by beauty.

Benefits Supervisor Sleeping, 1995

Portrait of Henrietta Moraes, 1963

One subject which seems to be forbidden today is the pretty young woman. It is as if ugliness were deemed automatically to be profound, and prettiness, superficial.

Even when Renoir was painting, he was reviled for painting this subject. Artists who paint beautiful women have rejected the temptation to render their work acceptable because it has an ugly subject. A beautiful subject counts against them.

Two Young Girls at the Piano, 1892

Renoir asked:

Painting is meant for decorating walls, isn’t it? So it should be as rich as possible. As far as I am concerned, a picture (since we have to do easel paintings) should be pleasing, cheerful, and pretty —yes, pretty! There are plenty of dull things in life without creating any more.

François Fosca (1881 – 1980)

‘Renoir, his Life and Work’ (1961)