“As our art is not a divine gift, so neither is it a mechanical trade. Its foundations are laid in solid science: and practice, though essential to perfection, can never attain to that which it aims unless it works under the direction of principle.”

Sir Joshua Reynolds, Discourse VI, December 10, 1774

When I was teaching portrait-painting to amateurs, I often noticed a perplexing development. Over the weeks, a keen student might make considerable progress. Then a certain point would be reached. The student would ask, “I have been doing all this work, but why don’t I just take a photograph instead?”

This question, in one form or another, has been coming up throughout my career, first as a student of drawing and painting, and then as a professional portrait painter. The question was not fully answered to my satisfaction during my training, even though I had the good fortune to be taught by artists whom I regarded as the best in the country. In the following pages I have attempted to condense my answer into the sort of book I would love to have had as a young teenager. I hope it will be of interest to students of all ages, at whatever stage of development they may be.

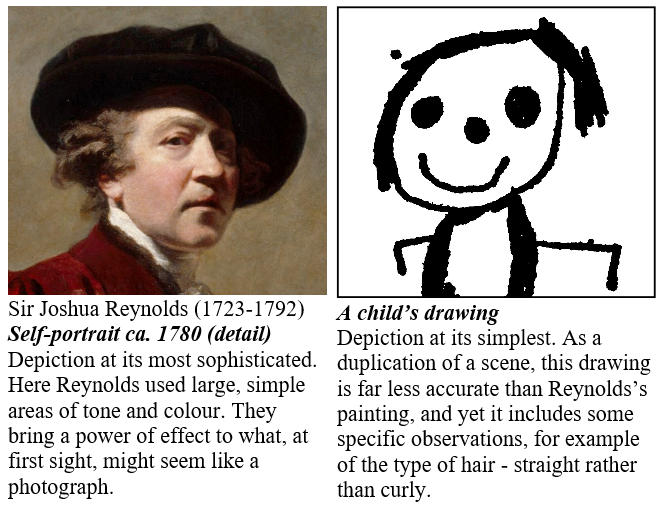

In one sense, the answer to the question, “why don’t I take a photograph instead?” is quite simple: an artist can draw lines, but a camera cannot. The implications of this are wide-ranging. They concern the essence of pictorial representation. One element, a line or a patch of colour, is used to stand in for something else, a strand of hair, for example. The artist makes and combines these elements. This is not the same as duplicating what appears in a viewfinder (an activity which is now carried out so well by photography).

Adults and children make dozens of decisions when drawing lines. For example, when representing some hair, a child must choose between making a line which is straight and one which is wiggly. Nothing equivalent to this sort of choice is open to the photographer. A camera cannot generate separate representational elements, adjust them and combine them. A photographic camera is designed to make recordings, not constructions.

Often a beginner does not recognise how much of his or her thinking about these representational elements is exposed on the paper or the canvas, and how interesting this can be for a viewer. Similarly art lovers may not be fully aware of the reason why, as they put it, paintings have ‘something’ that photographs do not.

A skilful painter can produce a picture which looks very like a photograph, but the signs of human thinking are just as evident in his or her work as they are in a child’s drawing – though the viewer may need to look with more care in order to discern them. Success in making a pictorial representation can be judged by a viewer who appreciates what the painter has been doing. So both painter and viewer need to have some understanding of the principle that has directed the painter’s work – that foundation in ‘solid science’ which Reynolds mentioned.

The more the viewer understands what to look for, the more fascinating the art of painting can become. In the chapters that follow I describe how artists have made images which look like real life, but which also demonstrate that they are independent combinations of lines and coloured shapes.