MAKING AN ACCURATE RECORD

When photography was invented a name had to be found for it. The light-sensitive surface in a camera records the light which comes through the lens, so the appropriate name for the technique would be Photogram (photo= light; gram = record). This name was indeed used in the early days of the development of the technique, but the word Photography became the accepted term. (photo = light; graph = drawing/ writing: so together they meant “drawing with light”). The term Photogram was forgotten, but years later Photogram was put to another use. It was applied to an image made by the shadows of objects which had been left on a light-sensitive surface.

So the word Photography is not really accurate. It implies that the photograph is a type of drawing, as if there was some intention involved in directing a line. So even the very name, Photography, embodies a claim that a photographic camera is actively making a drawing rather than passively making a record.

But it was the urge to record that gave rise to the development of photography, not the urge to draw. Fox Talbot (1800-1877), who made the first permanent negative on paper, described how it was his frustration at not being able to make an accurate record which made him look for a better method.

Lake Como

Photograph published in ‘Sunshine and Shadow’ 1892

Fox Talbot’s struggles to depict Lake Como using Wollaston’s camera lucida impelled him to invent a more convenient process, one which, four decades later, enabled Roome to record a view of that very Lake.

These were the two devices which were available to help Fox-Talbot make an accurate image, but which he found impractical.

One of the first days of the month of October 1833, I was amusing myself on the lovely shores of the Lake of Como, in Italy, taking sketches with Wollaston’s Camera Lucida, or rather I should say, attempting to take them: but with the smallest possible amount of success. For when the eye was removed from the prism — in which all looked beautiful — I found that the faithless pencil had only left traces on the paper melancholy to behold.

William Henry Fox Talbot (1800-1877)

After various fruitless attempts, I laid aside the instrument and came to the conclusion, that its use required a previous knowledge of drawing, which unfortunately I did not possess.

I then thought of trying again a method which I had tried many years before. This method was, to take a Camera Obscura, and to throw the image of the objects on a piece of transparent tracing paper laid on a pane of glass in the focus of the instrument. On this paper the objects are distinctly seen, and can be traced on it with a pencil with some degree of accuracy, though not without much time and trouble.

I had tried this simple method during former visits to Italy in 1823 and 1824, but found it in practice somewhat difficult to manage, because the pressure of the hand and pencil upon the paper tends to shake and displace the instrument (insecurely fixed, in all probability, while taking a hasty sketch by a roadside, or out of an inn window); and if the instrument is once deranged, it is most difficult to get it back again, so as to point truly in its former direction.

Besides which, there is another objection, namely, that it baffles the skill and patience of the amateur to trace all the minute details visible on the paper; so that, in fact, he carries away with him little beyond a mere souvenir of the scene — which, however, certainly has its value when looked back to, in long after years.

Such, then, was the method which I proposed to try again, and to endeavour, as before, to trace with my pencil the outlines of the scenery depicted on the paper. And this led me to reflect on the inimitable beauty of the pictures of nature’s painting which the glass lens of the Camera throws upon the paper in its focus — fairy pictures, creations of a moment, and destined as rapidly to fade away.

It was during these thoughts that the idea occurred to me. . .how charming it would be if it were possible to cause these natural images to imprint themselves durably, and remain fixed upon the paper!

And why should it not be possible? I asked myself.

The picture, divested of the ideas which accompany it, and considered only in its ultimate nature, is but a succession or variety of stronger lights thrown upon one part of the paper, and of deeper shadows on another. Now Light, where it exists, can exert an action, and, in certain circumstances, does exert one sufficient to cause changes in material bodies. Suppose, then, such an action could be exerted on the paper; and suppose the paper could be visibly changed by it. In that case surely some effect must result having a general resemblance to the cause which produced it: so that the variegated scene of light and shade might leave its image or impression behind, stronger or weaker on different parts of the paper according to the strength or weakness of the light which had acted there.

Such was the idea that came into my mind. Whether it had ever occurred to me before amid floating philosophic visions, I know not, though I rather think it must have done so, because on this occasion it struck me so forcibly. I was then a wanderer in classic Italy, and, of course, unable to commence an inquiry of so much difficulty: but, lest the thought should again escape me between that time and my return to England, I made a careful note of it in writing, and also of such experiments as I thought would be most likely to realize it, if it were possible.

The Pencil of Nature, 1844

https://archive.org/details/thepencilofnatur33447gut

Fax Talbot described how he set to work on his experiments. He succeeded in making photographic negatives on paper in 1835, but the images faded. This was remedied when, early in 1839, his friend, the scientist, John Herschel, suggested an effective chemical fixative.

Fox Talbot collected some of the images he had made, and, in 1844, published them in a book which he called, The Pencil of Nature.

THE INVENTION OF THE PERMANENT NEGATIVE ON PAPER

Nelson’s Column under Construction, Trafalgar Square, April 1844

An early use of photography to make a record of extreme accuracy and credibility.

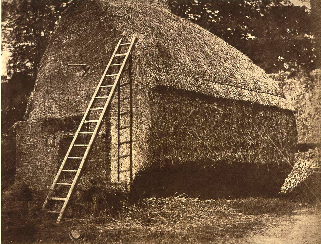

Haystack from ‘The Pencil of Nature’ 1844

Photography which demonstrates a careful selection of a striking scene, with a satisfying disposition of tonal areas.

The Author of the present work having been so fortunate as to discover, about ten years ago, the principles and practice of Photogenic Drawing, is desirous that the first specimen of an Art, likely in all probability to be much employed in future, should be published in the country where it was first discovered.

William Henry Fox Talbot (1800-1877)

It has often been said, and has grown into a proverb, that there is no royal road to learning of any kind. But the proverb is fallacious: for there is, assuredly, a royal road to Drawing, and one of these days, when more known and better explored, it will probably be much frequented. Already sundry amateurs have laid down the pencil and armed themselves with chemical solutions and with camera obscuræ. Those amateurs especially, and they are not few, who find the rules of perspective difficult to learn and to apply — and who moreover have the misfortune to be lazy — prefer to use a method which dispenses with all that trouble. And even accomplished artists now avail themselves of an invention which delineates in a few moments the almost endless details of Gothic architecture which a whole day would hardly suffice to draw correctly in the ordinary manner.

The Pencil of Nature, 1844

https://archive.org/details/thepencilofnatur33447gut

THE PENCIL OF MAN AND THE PENCIL OF NATURE

When Fox Talbot wrote about ‘the new art’ he was using the word ‘art’ to mean ‘technical process’. Today he might have described his invention as ‘a new recording technology’ – something that would record the image in the viewfinder with more accuracy than even a practised artist would have been able to achieve. Fox Talbot did not imply that photography was an art to rival painting except insofar as it was a means of making a record.

COMBINATION PHOTOGRAPHS

A Holiday in the Wood, 1860

Fox Talbot had devised the permanent negative in order to make a record of the scene in front of him, but soon others were claiming that photography could do more than that. It could be an art equal to painting (in all but colour). A strong advocate for this cause, Henry Peach Robinson, had begun as a painter. In 1852 he had exhibited a landscape On the Teme Near Ludlow, at the Royal Academy.

He began taking photographs that year, and went on to produce photographic prints that were made up of several photographs cut and pasted together. This sort of combination photograph is now very common, being far easier to achieve with a computer than it was by hand. He wrote a book, Pictorial Effect in Photography in which he argued that, by arranging the scene artistically, the resulting image would be as much a work of art as a painting. He discussed composition at length, but ignored the fundamental difference between drawing and recording. This confusion is as prevalent now as it was then.

Decades later, the naturalistic photographer, P. H. Emerson hinted at the difference between making a striking image, and one which showed the artist’s mind at work, when he wrote, about adjusting a photograph:

“…if for business, do what will pay.”

For example, someone who is making an advertisement may feel that the work requires a picture of, say, a pretty young woman. Whether the image is a painting or a photograph may make little difference to the appeal of the advertisement. Art does not come into the question, because the priority is to attract customers, not to please art-lovers.

A photograph’s status as Art comes under consideration only when a photographer claims that his or her art is equal to that of a painter. This claim almost always rests upon the skill which a photographer demonstrates when selecting and arranging what appears in the viewfinder. This skill is one which Henry Peach Robinson had developed to a high degree, but his combinations came to be disparaged by later photographers. They felt that, by manipulating the image, he had compromised with painting, and thus invalidated any claim that his photography could be an independent art form.