PICTORIAL PHOTOGRAPHY AND PURE PHOTOGRAPHY

The Fringe of the Marsh 1886

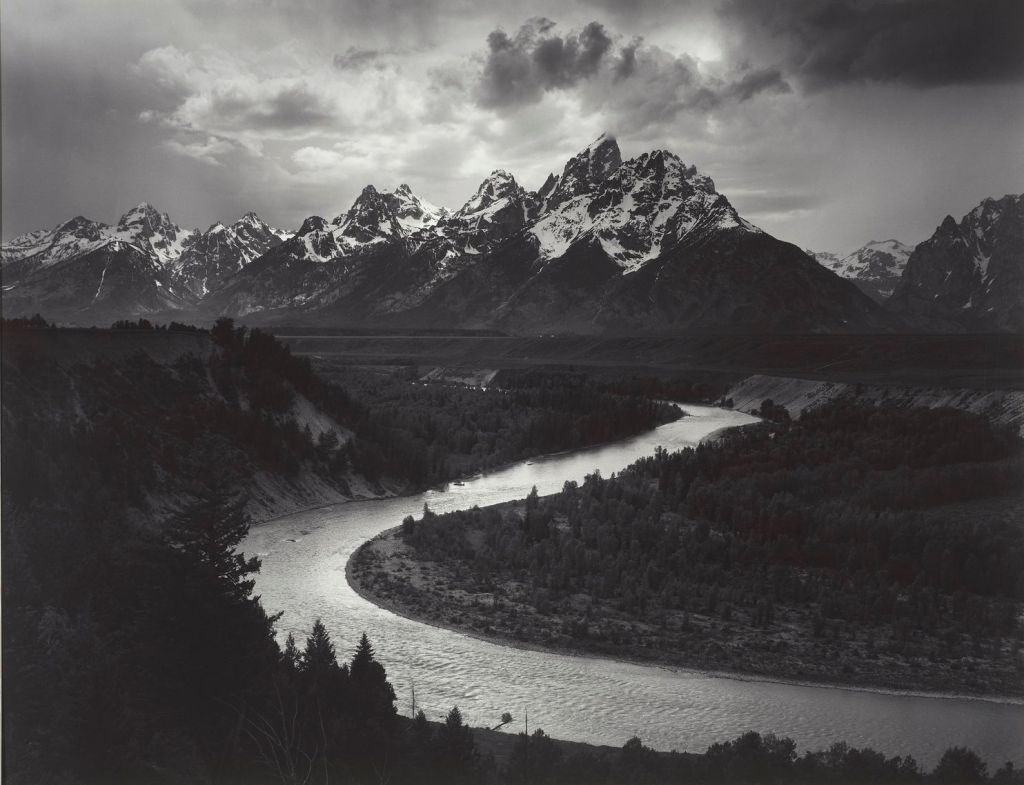

The Tetons and Snake River,

Grand Teton National Park,

Wyoming, 1942.

Emerson may have mourned the death of Naturalistic Photography, but others continued to hope that a mechanical record could be an artistic product on the same level as a drawing or painting.

In order to demonstrate that their art was totally independent from painting, the mechanical nature of photography had to be emphasised, even exaggerated. The work would then be an example of ‘pure photography’ unmixed with any hint of painting.

One factor which distinguished photography was ultra sharpness. For maximum sharpness, photographers selected an aperture of f/64, (the smallest aperture which does not degrade the image with effects of diffraction). This became the name of one of their clubs: ‘Group f/64’.

https://www.theartstory.org/movement/group-f64/

Naturalistic and pictorial photographers had been able to control the degree of blur by using a wide aperture and focussing on the parts of the subject which they wanted to emphasise. But this control resembles that of the painter, who is free to blur any part of the image. Pure photographers rejected all such painterly controls. Photography could now be concerned exclusively with selecting and arranging what appeared in the viewfinder, and with pressing the shutter-release at the appropriate time.

This is what one of pure photography’s main proponents, Edward Weston, came to believe, and to express in a famous passage from one of his notebooks, referring to the following photographs:

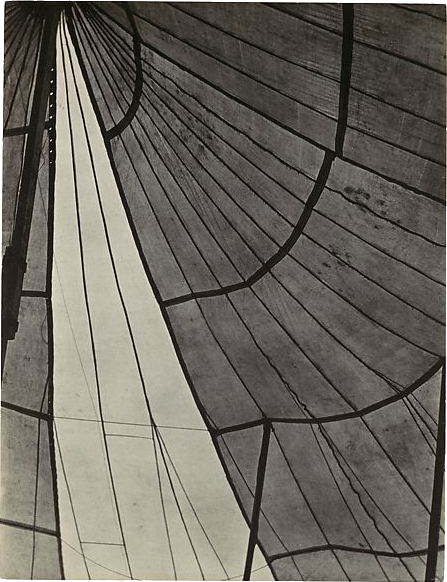

Circus Tent 1924

San Pedro y San Pablo, 1924

Lupe Marín de Riviera , 1923–1923

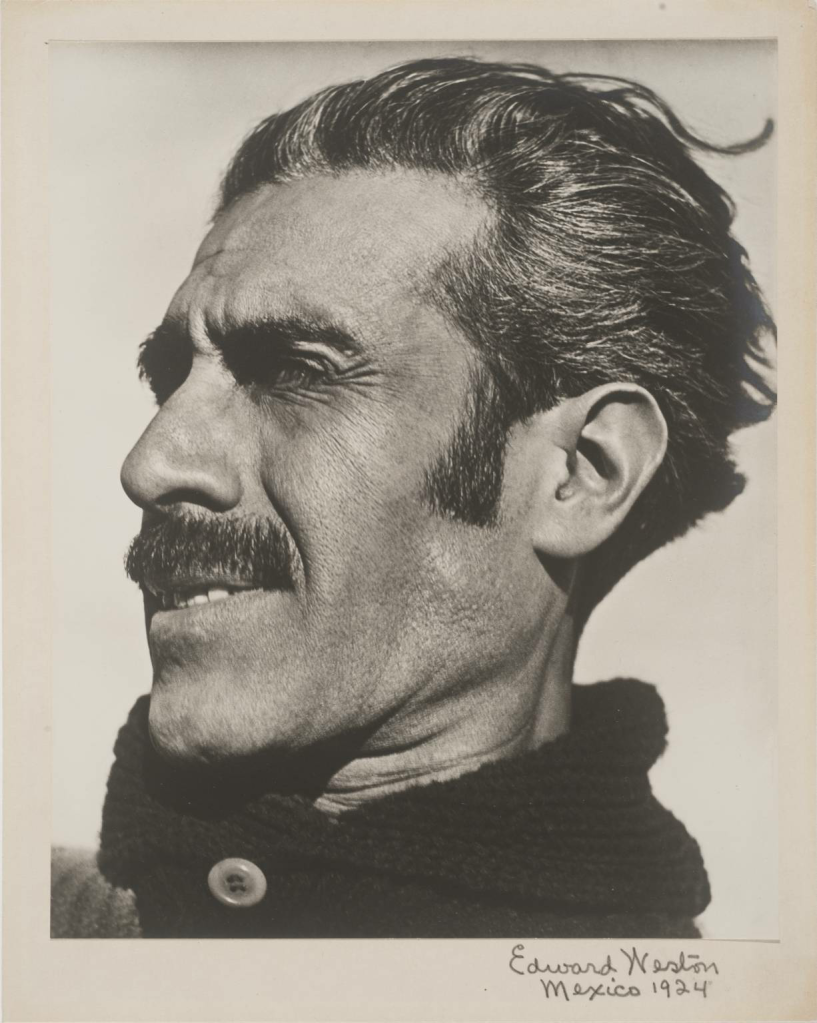

Manuel Hernandez Galván, Mexico 1924

Tina Modotti reciting 1924

Visiting the museum last week focused my thoughts once more on the issue of photography. For what end is the camera best used aside from its purely scientific and commercial uses?

From the Daybooks of Edward Weston, March 10, 1924

The answer comes always more clearly after seeing great work of the sculptor or painter, past or present, work based on conventionalized nature, superb forms, decorative motives. That the approach to photography must be through another avenue, that the camera should be used for a recording of life, for rendering the very substance and quintessence of the thing itself, whether it be polished steel or palpitating flesh.

I see in my recent negatives of the circus tent and of the glass roof and stairway at San Pablo — pleasant and beautiful abstractions, intellectual juggleries which presented no profound problem. But in the several new heads of Lupe, Galvan, and Tina, I have caught fractions of seconds of emotional intensity which a worker in no other medium could have done as well.

I shall let no chance pass to record interesting abstractions, but I feel definite in my belief that the approach to photography is through realism — and its most difficult approach.

For collections of Weston’s photographs see:

https://www.artic.edu/collection?artist_ids=Edward%20Weston&page=1

and

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search#!?q=Edward%20Weston&perPage=20&sortBy=Relevance&offset=0&pageSize=0

However, not everyone was ready to accept that photography was as limited as this, not even Weston himself. Despite his belief that the approach to photography must be through ‘realism’, in practice this did not mean that the result would be a scientifically correct photograph. Pure photographers were not interested in tonal accuracy, as long as their works were clearly unlike paintings. (Ansel Adams developed his ‘Zone System’ to help control tonal effect, not accuracy.)

Artichoke Halved 1930

Pepper 1930

CONTRAST

It is a feature of vision that a sharp photograph appears to be higher in contrast than the same photograph blurred. Increased contrast gives the impression of increased sharpness – thus making the photograph look even more pure.

Pure photographers applied such adjustments across the whole image, or selected areas, lightening or darkening them by applying the techniques called ‘dodging’ and ‘burning’. A viewer of the photograph would not be able to tell whether the clouds in a sky had been made brighter, for example, or whether they really had been that bright in the viewfinder. From the viewer’s point of view, a sharp, tonally falsified photograph appears just as pure as a photograph which is scientifically accurate.

This led to a famous quotation which appears in many articles and websites.

Mount Williamson, Sierra Nevada, from Manzanar,

California1944

Dodging and burning are steps to take care of mistakes God made in establishing tonal relationships.

Attributed to Ansel Adams, (though I have been unable to verify the source).

Adams rejected overt manipulation, but felt that it was ‘ridiculous’ not to use photographic controls, as long as the result had an appearance which he called, ‘photographic’. By ‘photographic’ Adams seems to have meant: sharply-focussed, contrasty, highly-detailed, and unnatural in appearance. His photographs do indeed have a sense of unreality about them.

For Adams, to change tonal values was to exercise ‘legitimate control’. He did not classify such adjustment as manipulation, even though that is exactly what it is. But he did not extend ‘legitimate control’ to the adjusting of shapes – the narrowing of a model’s waist, for example. There seems to be no logical reason for this discrimination, since a photograph which has been manipulated in shape can look every bit as ‘photographic’ as one which has been manipulated only in tonal value.

Adams wrote:

I do not retouch or manipulate my prints because I believe in the importance of the direct optical and chemical image. I use the legitimate controls of the medium only to augment the photographic effect. Purism, in the sense of rigid abstention from any control, is ridiculous; the logical controls of exposure, development and printing are essential in the revelation of photographic qualities. The correction of tonal deficiencies by dodging, and the elimination of obvious defects by spotting*, are perfectly legitimate elements of the craft. As long as the final result of the procedure is photographic, it is entirely justified. But when a photograph has the ‘feel’ of an etching or a lithograph, or any other graphic medium, it is questionable––just as questionable as a painting that is photographic in character. The incredibly beautiful revelation of the lens is worthy of the most sympathetic treatment in every respect.

From ‘A Personal Credo’ American Annual of Photography 1944

Article by Ansel Adams (1902 – 1984)

Creative Camera magazine.

*Prints often show white spots, made accidentally when particles of dust have come into the process somewhere. Photographers may retouch these white spots with paint so that they do not spoil the picture.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spotting_(photography)

So pure photography turned out to be the same as scientific photography, except that pure photographers might manipulate tonal values (but not shapes). Few photographers have been content to accept this arbitrary restriction, but the legacy of the movement affects almost all working in the field. Most exhibitions of famous photographs taken after, say, 1935, are dominated by images which look unreal and peculiar. It is as if photographers were showing a world reminiscent of the one we live in, but deliberately falsified.

As a record of a scene, a pure photograph is at the opposite extreme to an impressionist painting. A French Impressionist painting of about 1870 looks convincing as a true record of the world we live in, but on close inspection it is very far from complete. It is made up of separate patches of colour, not of continuous tone. It might be said that a French Impressionist painting is an incomplete record of visual truth while a pure photograph is a complete record of visual falsehood.

Both pictorial photography and pure photography are purposely inaccurate. The pictorial photographer removes details which distract in the photograph but would not distract in real life, while the pure photographer tends to emphasise these same details, because they make the image look distinctively photographic. Neither produces images which could be classed as ‘scientific’; that is, which match what appears in the viewfinder. Modern exhibitions of photographs rarely show an example of true-to-life tonality. Such photographs would look too much like Dutch paintings of the 17thC to be acceptable. (The Dutch of that period having produced superlative examples of pictures that were accurate in tone and colour).

The pure photographer typically chose subjects which were relatively static, although seizing the moment could also be important, as we have seen with Weston. Some critics draw a distinction between ‘journalistic’ photographers, who seize the moment, and ‘fine art’ photographers, who take more time to select and arrange scenes which look considered rather than snatched. Journalistic photographers often have no pretensions to call themselves fine artists. The most prominent of these was Henri Cartier-Bresson, who published a book of his photographs which he entitled, ‘The Decisive Moment.’

An example of ‘candid’ or ‘street’ photography. A decisive moment has been captured.

A moment.

Whereas pure photographers would choose a subject for its potential to make a picture that was distinctly photographic in appearance, sharp and harsh, the street photographer or photo-journalist, looked for eye-catching subjects, regardless of how the image might be processed in the darkroom. The task of printing might even be handed over to a technician, someone who might employ all sorts of tonal manipulations. But the photographer did not attach excessive importance to this. Having taken a photograph, one may as well have it processed so that it is as striking as possible. Cartier-Bresson expressed the relationship exactly:

He often described his method in the imagery of a hunter or a fisher.

https://newint.org/columns/essays/2004/10/01/cartier-bresson/

‘One is, alas, always an intruder,’

he used to say, even in the infancy of photo-journalism in the 1940s, referring to the camera’s invasive properties and its implication in the regimes of spying and surveillance – which have become so problematic in recent times.

‘Approach the subject on tiptoe… Let your steps be velvet but your eyes keen. A good fisherman does not stir up the water before he starts to fish.’

Explaining why he never went into the darkroom to process his films – leaving it in the masterly hands of the equally legendary Pierre Gassman – he used to say:

‘I’m only a hunter, not a cook.’

Retrieved 22 October 2021

In aiming to produce an art of photography that was totally distinct from painting, the pure photographers gave prominence to a ‘photographic’ look which is still influential. The claim that theirs was an art equivalent to painting rested on legalistic arguments about ‘legitimacy’ and not on appearance. Photographs remained copies of what appeared in the viewfinder, no matter how carefully photographers might select and arrange the scene, and no matter what use they made of ‘legitimate controls’ to manipulate the result.