EMERSON – THE DEATH OF NATURALISTIC PHOTOGRAPHY

The Fringe of the Marshes, c1888

A photograph in which Emerson demonstrated the subtle use of blurring achieved without retouching the original photograph.

Nocturne in Grey and Gold: Chelsea Snow, 1876

A painting in which Whistler demonstrated a wide range of blurring contrasted with sharp touches.

Colts on a Norfolk Marsh 1890

Despite renouncing the claim that photography could be an art equivalent to that of painting, Emerson continued to produce striking photographs.

The Pool, 1859, etching and drypoint

Even though he took blurring to an extreme in painting, Whistler was a master of line.

In his Naturalistic Photography, Emerson advocated the naturalistic approach, claiming that it could give rise to an art that was potentially equal to that of painting. His book even went into a second edition. However, within a year, Emerson realised that his claim had been absurd. With great regret, he published The Death of Naturalistic Photography. Emerson recognised that a photographic image was unable to display what he termed, “differential analysis”. It could only be the record of a scene, not a construction made by the photographer.

He clearly found this conclusion intensely disappointing, though by no means did it mark the end of his interest in photography. A decade later he published a third edition of Naturalistic Photography, but only after having deleted all claims that photography could be anything more than an art that was very limited. After his Renunciation, Emerson lived a further 46 years. Despite witnessing the many remarkable advances in the technological side of photography, which took place during this period, he saw no reason to change his mind.

His renunciation is a strange document, written in a mock funerary tone, but it includes passages of serious analysis. (I have included it here, because it is not readily available to most readers). He confessed that he had not properly appreciated what had formed the substance of the art of drawing and painting.

(See also: https://www.tate.org.uk/research/publications/tate-papers/27/emersons-evolution)

He wrote that he had,

… preached that all art that did not conform to “truth to nature” principle was bad…

P.H. Emerson (1856 – 1936)

The Death of Naturalistic Photography 1890

But, having given the matter more thought, he had come to realise that this was not so:

To you, then, who seek an explanation for my conduct, Art – as Whistler said – is not nature – is not necessarily the reproduction or translation of it – much, so very much, that is good art, some of the very best – is not nature at all nor even based upon it – vide Donatello and Hokusai.

Virgin and Child ca. 1455-1460

This relief shows Donatello’s dependence on line.

Lake Suwa in Shinano Province

In this print, Hokusai used characteristic lines and colours. These are unlike what someone might have noticed on the spot, whether looking through a viewfinder, or viewing the scene in a mirror; and yet they make a telling representation

“…SOME OF THE …BEST [ART] – IS NOT NATURE AT ALL NOR EVEN BASED UPON IT…”

In other words, Emerson had come to understand that representational Art was not concerned with duplication, but with using one thing to stand for another – a rough circle to represent a head, for example. ‘Holding a mirror up to Nature’ was not, after all, the great goal of Art. Lines, for example, may be employed to represent the world felt and seen, but they are independent of that world.

Although a photographer might control an image to a ‘slight degree’, this control was puny. Even a child scribbling had far more power. The art of photography was limited to selecting and arranging what appeared in the viewfinder, and making a copy of that image – sometimes touched up in a variety of ways.

Some have argued that Emerson’s remarks applied only to the limited techniques of his time, and that, if he had seen the developments in colour photography and in computer manipulation, he would have revised his opinion. But Emerson was dealing with principles, just as Sir Joshua Reynolds had been dealing with them in the previous century (when he had rejected copying the image in the camera obscura). No matter how much technology may advance, the camera can never draw a line.

P. H. Emerson:

[1] Hurter (1844–1898) and Driffield (1848–1915) were photographic scientists who studied the sensitivity of photographic materials. Reading their papers convinced Emerson that very little could be done to change this sensitivity. Computer technology has brought a greater range of possibilities, but it is still true that if one object is darker than another, it will remain so in the photograph, otherwise the result will usually look unnatural.

The limitations of photography are so great that, though the results may and sometimes do give a certain aesthetic pleasure, the medium must always rank the lowest of all art, lower than any graphic art, for the individuality of the artist is cramped, in short, it can scarcely show itself. Control of the picture is possible to a slight degree, by varied focussing, by varying the exposure (but this is working in the dark), by development, I doubt (I agree with Hurter and Driffield [1], after three-and-a-half months careful study of the subject) and lastly, by a certain choice in printing methods.

The tones of individual areas can easily be changed with the help of a computer programme such as Photoshop, but doing so is equivalent to painting on the photograph, something which would reduce the independence of Photography as an art form.

He wrote that it was impossible to get, “the values in any subject whatever as you wish”.

(Emerson was referring to tone values. For example a dark area is of a low tone value, whereas a pale area is of a high tone value).

With the advances in digital manipulation, it is indeed now possible to transform any value at will, so Emerson’s words on that subject no longer apply. But he compared the tone-values in a photograph with tone-values in a drawing by Rico or Vierge.[2] Even today it would be impossible for a photographer to imitate such works, unless he or she were actually drawing – either on paper or on a computer.

[2] Drawings by Rico and Vierge had recently appeared in, ‘Pen Drawing and Pen Draughtsmen’, Joseph Pennell 1889.

The Shop, an Exterior, c. 1883–85

A painting which shows Whistler’s fastidious control of selection and emphasis.

A Spanish painter of landscapes and cityscapes.

A Spanish painter of landscapes and cityscapes.

A Spanish-born French illustrator who revolutionized the reproduction of illustrations.

These illustrations demonstrate the use of line, something which is impossible in photography.

The Girl at the Gate 1889

Clausen, a very naturalistic painter, may have been the ‘great artist’ who pointed out the limitations of photography to Emerson.

Emerson mentioned how misgivings had seized him after conversations with ‘a great artist’. It is often assumed that this artist must have been Whistler (though it is possible it was Clausen). In addition, the exhibition of Hokusai’s work which he mentioned must have provided the strongest possible contrast to the image in the viewfinder. Hokusai’s prints demonstrate that the essential character of drawing and painting is line – line which shows that the mind has determined the limits of one object or area. Whistler’s work is often made up of coloured patches – the edge of one melding into the edge of another. But, however soft these edges may be, their placing is determined by the artist. They are, in essence, blurred lines. This linear basis may be seen in Whistler’s drawings more easily than in his paintings.

P. H. Emerson:

P.H. Emerson (1856 – 1936)

Some of my friends to whom I have recently privately communicated my renunciation, have wished to know how it came about. Misgiving seized me after conversations with a great artist, after the Paris Exhibition; …and finally the exhibition of Hokusai’s work and a study of the National Gallery pictures after three-and-a-half months’ solitary study of Nature in my house-boat did for me.

The Death of Naturalistic Photography 1890

Emerson’s renunciation infuriated many of his followers, and his arguments still meet with powerful opposition.

The photographer, Eric de Maré (1910-2002), pointed out where he thought Emerson’s thinking had been fallacious. De Marés arguments continue to be put forward, even today, so it may be worth reviewing them here. I have added footnotes where it seems clear that it was de Maré who was mistaken, not Emerson.

Moulsford Railway Bridge

This photograph is an example of de Marés skill at selecting a striking subject and framing it effectively.

St Edwards, Brotherton, North Yorkshire, with Ferrybridge B Power Station behind (1960s)

Souce: RIBA British Architectural Library Photographs Collection

An example of the photography for which de Maré was particularly admired.

https://www.architectsjournal.co.uk/practice/culture/the-exploring-eye-the-photography-of-eric-de-mare

De Maré wrote in Photography (1957) page 40:

De Maré:

[1] Emerson did not say that photography was an illegitimate form of art, but that, as an art, it was very limited.

Then, suddenly, Emerson decided that it was wrong to confuse art with nature, and renounced his former claim that photography was a legitimate form of art. [1] All that photography could and should do, he said, was to represent nature and nature was not art. In his Death of Naturalistic Photography he boldly proclaimed:

P. H. Emerson:

P.H. Emerson (1856 – 1936)

I throw my lot in with those who say that photography is a very limited art. I deeply regret that I have come to this conclusion…. The all-vital powers of selection and rejection are fatally limited, bound in by fixed and narrow barriers. No differential analysis can be made, no subduing of parts, save by dodging – no emphasis, save by dodging, and that is not pure photography. Impure photography is merely a confession of limitations.

The Death of Naturalistic Photography 1890

De Maré:

[3] De Maré did not say what these ‘false premises’ were; perhaps that photography should be true to Nature? Some argue that photography does have a certain power to select and reject; by lighting, framing and arranging the subject, or by adjusting the image in the darkroom or on the computer. However these activities are all concerned with selecting and arranging a scene, not with representing it.

Of course, within his false premises [3] Emerson was right. He failed to see, as we see to-day, that photography has very great powers of selection and rejection but not in the way Emerson meant. [4]

Even an incompetent beginner can draw a line to represent something – no matter how crudely – thus demonstrating differential analysis at its most basic. This is totally impossible for photographers, no matter how brilliant and perceptive they may be.

[4] Emerson understood that photography had the capability to distort the image – and thus demonstrate a power of selection and rejection. He recognised that photography would gain more of this power as the technology improved. For example, contrast, sharpness, and blurring can be adjusted with ever greater precision, and this can produce striking effects.

But Emerson deplored such effects when they detracted from arguably photography’s greatest power – its credibility, its truth to nature. (See his rules for Naturalistic Photography in the previous chapter).

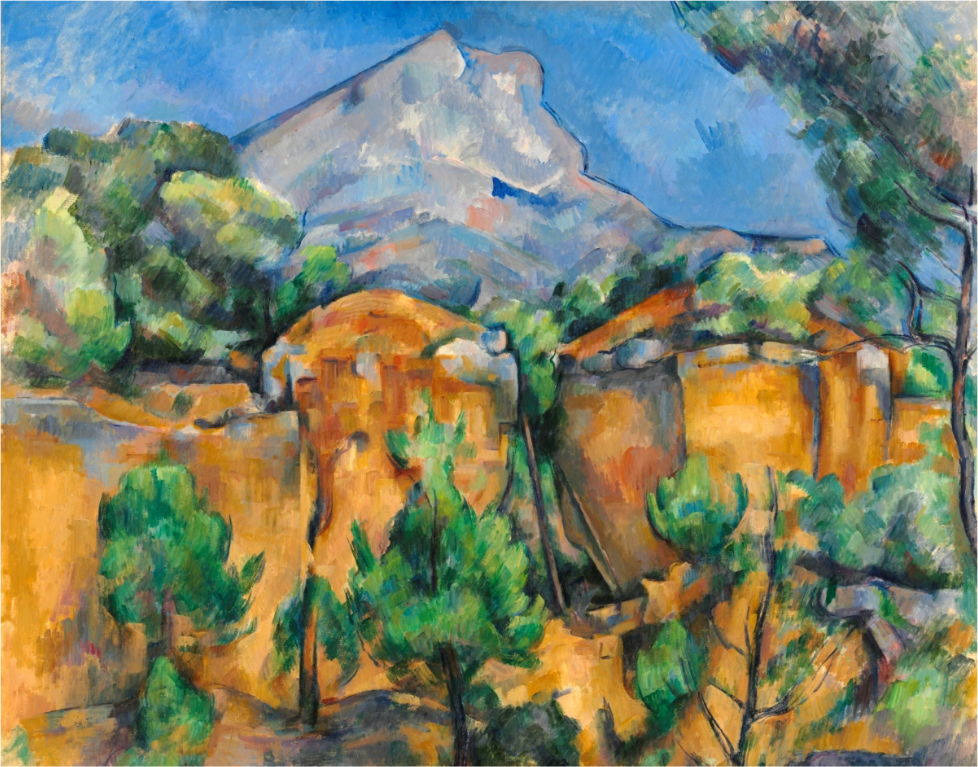

Montagne Sainte-Victoire

Photograph from https://drawpaintacademy.com/

This photograph was taken from approximately where Cézanne set up his canvas. The distortions which the artist made are striking, as is the way in which he constructed his painting with lines and areas that give a sense of volume.

Montagne Sainte-Victoire seen from the Bibémus Quarry – circa 1897

Cézanne set out the outlines of objects very clearly, but also broke them up, so that the viewer’s eye is led across the painting in an intriguing way. The result is very different from a photograph.

De Maré:

[5] On the contrary, Emerson referred to the entire history of Art when he wrote: “much, so very much, that is good art, some of the very best – is not nature at all nor even based upon it.”

…At that time, too, aesthetes could hardly disassociate the word Art from the term Graphic Art, and Graphic Art often meant the making of your representations ‘true to Nature’, even if you obtained your effects by roundabout means such as the Impressionist painters used. [5]

De Maré:

[6] By no means did Cézanne ‘change all that’. Emerson mentioned artists who, over many centuries, had not been attempting to be true to Nature.

In painting Cezanne changed all that, [6] even though he himself was always trying to discover Nature’s visual secrets. After him photographers began to think consciously about Form-for-form’s-sake, and to realize that the camera could select Significant Form [7] from the chaos of the whole visual environment and could make an aesthetic comment upon it. [8]

[7] ‘Significant form’ was a term introduced by art critic Clive Bell (1881-1964), and explained in his book ‘Art’ (1914). Some shapes and colours and their combinations are more pleasing or engaging than others, irrespective of what they represent, and to that extent Bell considered their form to be more ‘significant’. “In primitive art you will find no accurate representation ; you will find only significant form.”

Bell’s book is entirely about forms made by people, not found in nature, so De Maré’s claim that a camera could select significant form is meaningless in Bell’s terms. Form must be made, not copied.

Bell wrote (p229): “…an artist creates a good design when, having been possessed by a real emotional conception, he is able to hold and translate it…”

(The artist does not produce significant form by making) “literal transcriptions from nature…” (A photograph is a literal transcript from nature).

[8] A photographer is holding a mirror up to nature – selecting what appears in the viewfinder: he or she is not making an ‘aesthetic comment’. Even if one subscribes to the theory of ‘significant form’, making such a form is different from causing it to be reflected in a mirror or to be framed in a viewfinder.

De Maré:

[9] The difference between photographing and painting is the same as the difference between recording an orchestra and composing a symphony. This distinction is not the result of a confusion about words.

All such arguments as Emerson raised are brought about by semantic confusion – confusion about words. [9] To Emerson, as to so many others (yes, even now), the words Art and Painting were often considered to be synonymous. The photographer indeed often feels himself to be a somewhat inferior kind of artist to the painter instead of an artist working in a different medium from the painter. If painting is superior to photography as a medium its superiority lies both in being less restricted and in showing that almost direct touch of the human hand which gives it a special charm of its own. [10]

[10] Emerson fully recognised that there was an art in selecting what appeared in the viewfinder, but he also recognised that this art was very limited compared with the art of painting.

The ‘special charm of the direct touch of the human hand’ is of little importance compared with the power of drawing that a painting displays – the power of a mind at work. (Seen, at its most basic, in the making of a line – however badly). Similarly, the words that writers write are far more important than their handwriting – however charming it may be.

Emerson wrote: “I have, I regret it deeply, compared photographs to great works of art, and photographers to great artists.”

De Maré:

[11] Painters have no need of this instruction. They were quick to use photographs as aids as soon as they became available. Emerson had written in Naturalistic Photography (2nd ed.), “The daily use made of photography by artists is another proof of the good opinion in which it is held by them.” In his Renunciation he wrote that, “photography was the ‘hand-maiden of art and science”.

But the painter should bless photography, [11] partly because the new ways of seeing things which photography has given us has stimulated the painter’s imagination and partly because its challenge in the early days revitalized painting and forced the modem movement into being; it compelled painters to depart from academic, naturalistic representation which was a realm where the camera showed itself to be much more efficient and successful with much less effort. [12]

The great French painter Delacroix (1798-1863) had written: “Let a man of genius make use [of photography] as it should be used, and he will raise himself to a height that we do not know.”

[12] No doubt photography did have an effect in putting some painters out of work – most painters of miniature portraits, for example, had either to give up or to become photographers themselves – but this was because such paintings were made primarily as recordings, not in order to show the artist’s mind at work.

Art, for almost its entire history, had been preoccupied with concerns other than duplicating a mirror. In the seventeenth century, many artists did imitate mirrors, Rembrandt for example in his famous series of self-portraits; but such artists were always aware that a pure duplication of the mirror image would be unsatisfactory.

The new emphasis on line which started around 1880 came after Art had completed the cycle of line, form, tone and colour which Brian Thomas described in ‘Vision and Technique in European Painting‘ (1952). In search of novelty, artists were bound to return to line.

Photography did have an influence, but only in helping art move in the direction it was going already. Photography did not compel artists to change, at least not those working at the highest level, any more than the camera obscura had compelled them to change in the 17th Century.

Photograph taken, under the artist’s direction, by Jean Louis Marie Eugène Durieu (1800–1874)

and a drawing of 1855.

Delacroix’s drawing shows how he analysed the photograph, just as he would have analysed Nature.

Photograph taken, under the artist’s direction, by Jean Louis Marie Eugène Durieu (1800–1874), and a drawing of 1855

Delacroix’s drawing shows how he analysed the photograph, just as he would have analysed Nature.

Delacroix’s inaccuracies, show what he considered to be important in the subject. They are informative in a way that a photograph cannot be.

So even today, more than a century after Emerson made his renunciation, his arguments still hold. It may be worth pointing out that these arguments are much the same as those that Sir Joshua Reynolds had advanced as long ago as 1786. It was not necessary to invent photography in order to recognise the difference between art and nature.

Apart from painterly touching up on the computer, the art in photography lies entirely in selecting and arranging what appears in the viewfinder. But some photographers continue to argue that their art is equivalent to the art of painting – as if their words could prevent viewers from believing the evidence of their eyes.

Magdalena Dalton

An example of miniature painting, an art that was largely superseded by photography.

(A miniature is a painting that is small enough to be held in the palm of the hand).

Woman in Flowered Bonnet

An example of a hand-tinted daguerreotype, a kind of photography which largely replaced miniature painting.

(Daguerrotype was the first publicly available photographic process; it was widely used during the 1840s and 1850s. “Daguerreotype” also refers to an image created through this process.

Invented by Louis Daguerre and introduced worldwide in 1839.)

Self-Portrait with Two Circles c. 1665–1669

A painting of an image in the mirror, but clearly not a photographic duplication.