WÖLFFLIN – LINEAR VS. PAINTERLY

Wissenschaftliche Sammlungen der HU Berlin,

ID 13758, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=6326670

Heinrich Wölfflin (1864– 1945) was a Swiss art historian, whose objective classifying principles (“painterly” vs. “linear” and the like) were influential in the development of formal analysis in art history in the early 20th century.

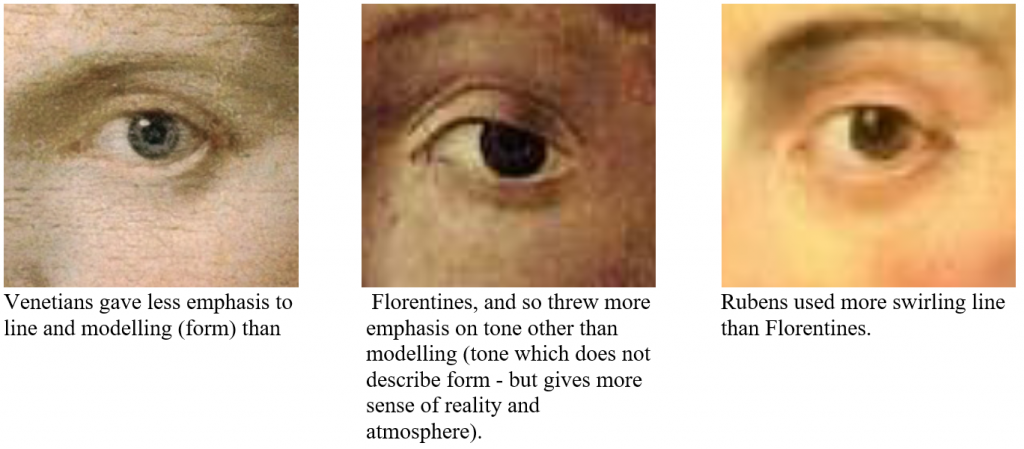

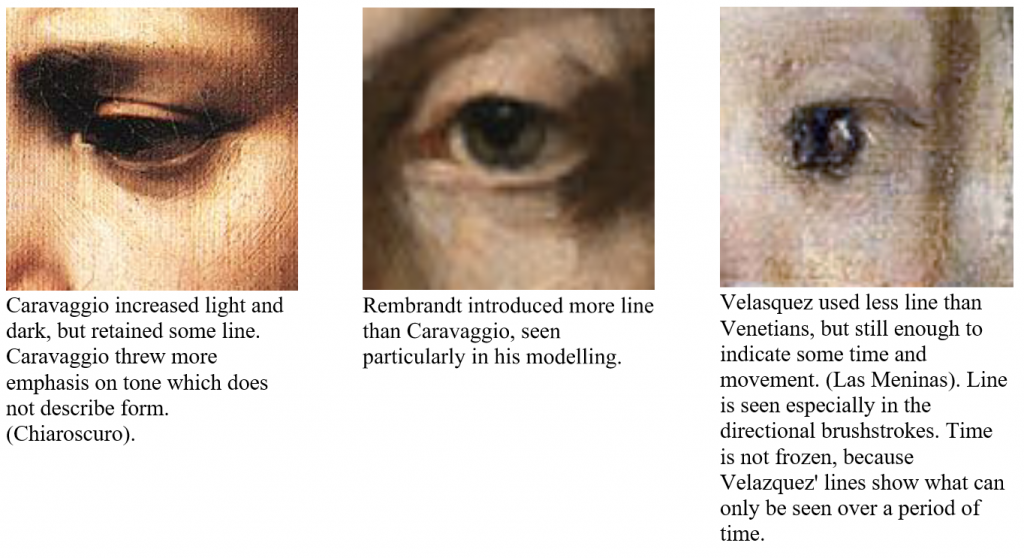

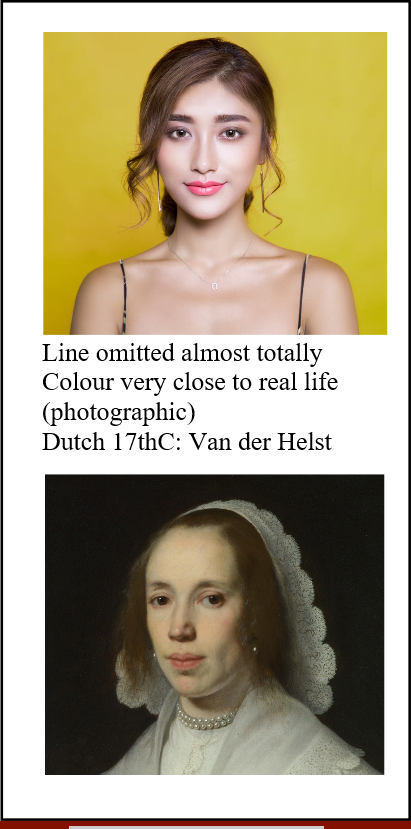

PROGRESSION FROM LINE TO PHOTOGRAPH

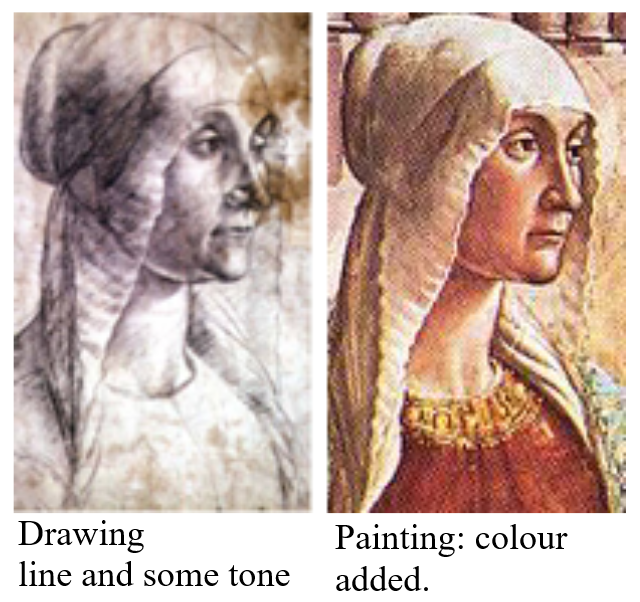

A representational painting is made up of two components:

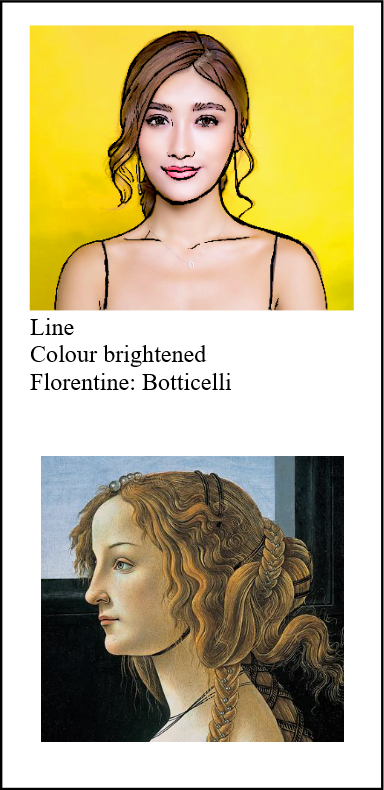

1. Line. Which does not exist in Nature, and

2. Colour. Which does exist in Nature.

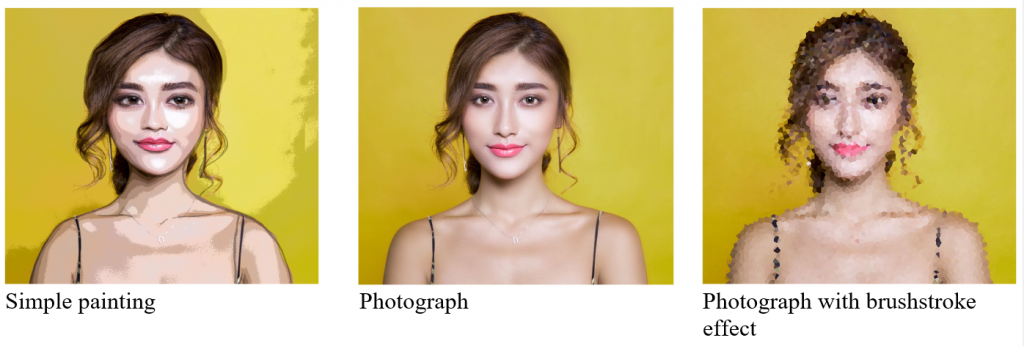

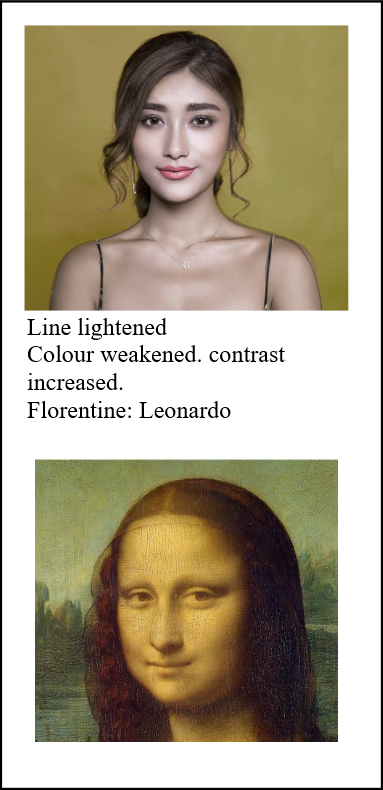

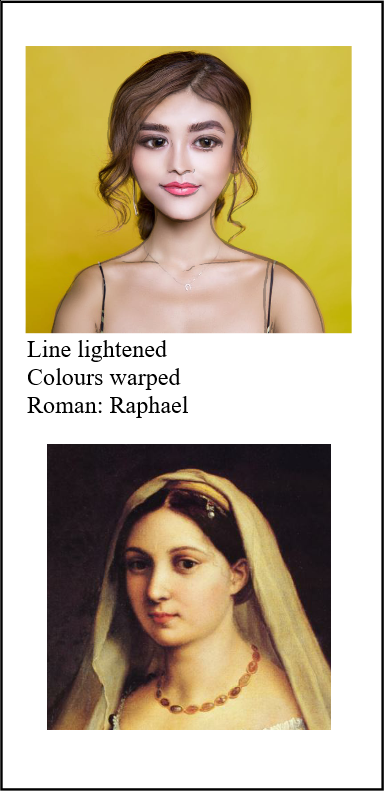

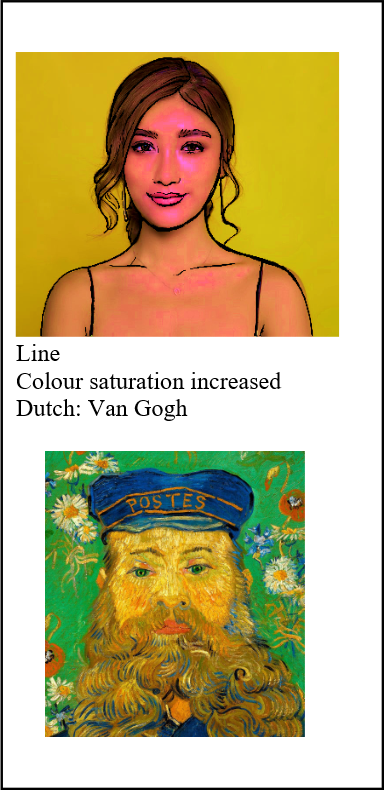

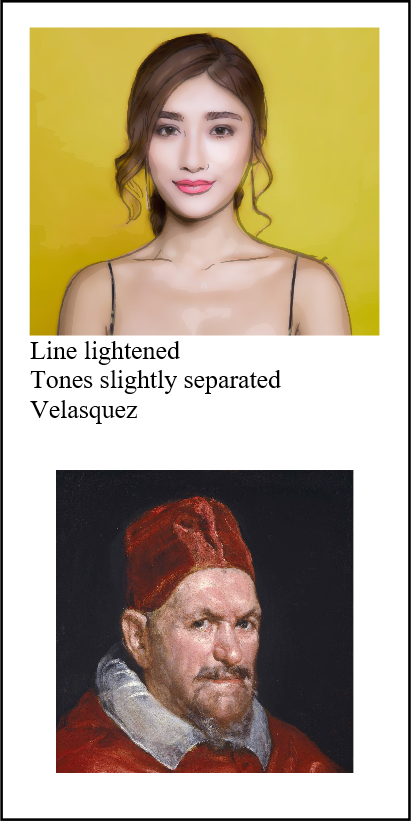

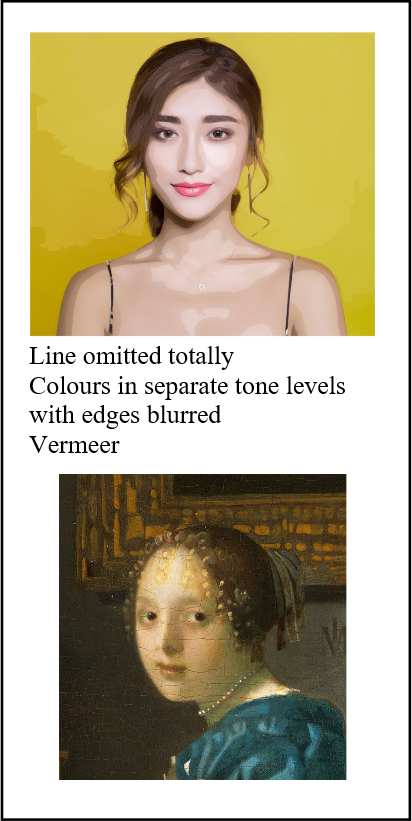

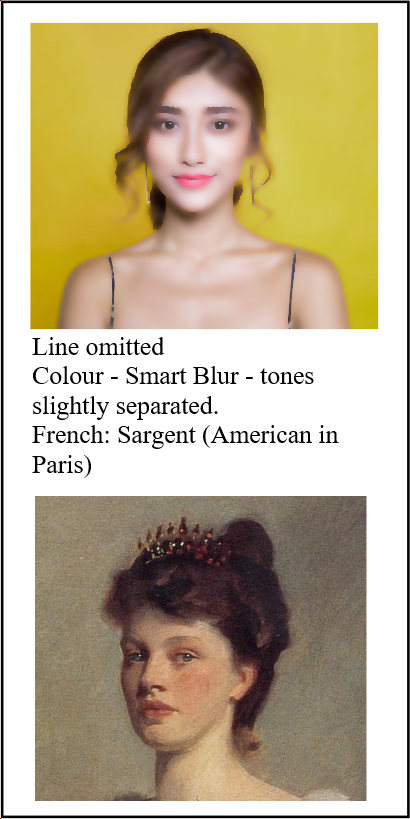

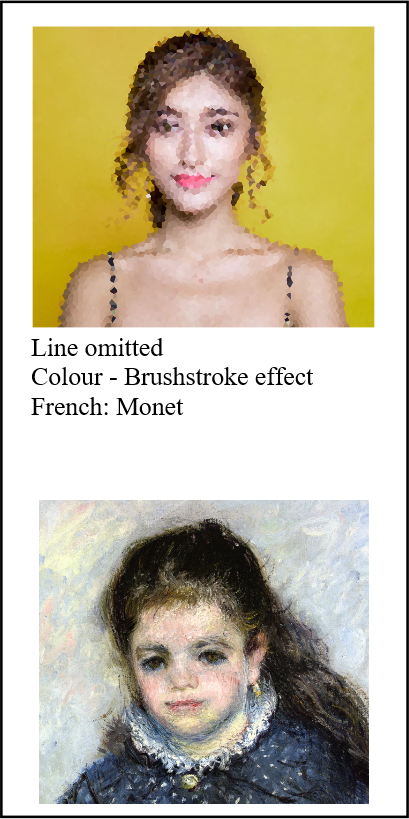

Line and colour may be each be treated in many ways, and combined to produce an infinite range of styles. I have shown some of the many possibilities by applying stylistic variations to a single photograph. Paintings by varitous artist show these variations, but subject matter can confuse the issues. The stylistic possibilites are far greater with painting than with photography; yet another example of the truth of P.H.Emerson’s observation – that photography is a very limited art compared with that of painting.

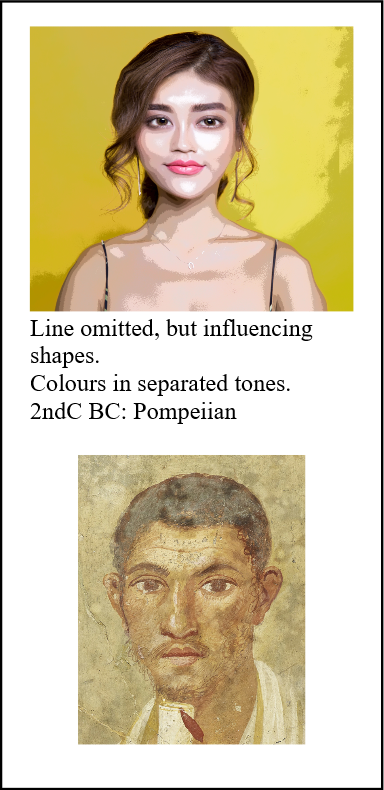

It has often been said that there are no lines in Nature, only in Art; whereas colour exists in both Nature and in Art. So it is lines which most distinctly identify a picture as a work of art rather than as a copy of nature.Even when lines have been covered over with colour, evidence of them may remain in coloured patches, the shape of which was dictated by the now invisible line.

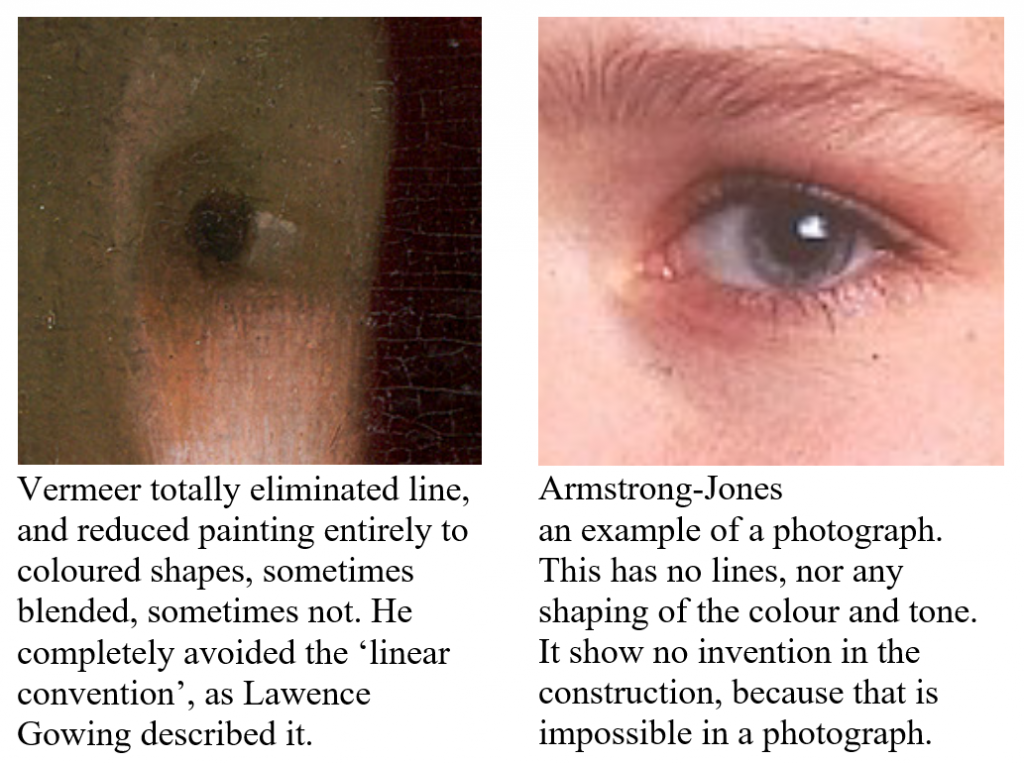

The artist may make his picture resemble more and more what might be seen in a static viewfinder, so that the picture comes increasingly to resemble a photograph, and the line disappears altogether.

Many artists are able to work without even drawing preparatory lines, so that line and colour become inextricably combined.

Detail from The Birth of Mary

Date: 1486 – 1490

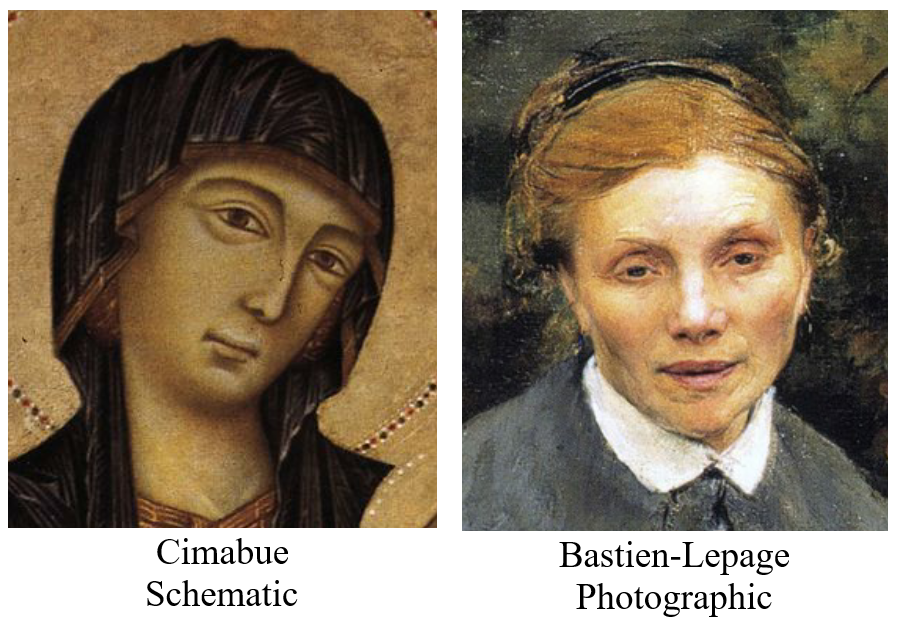

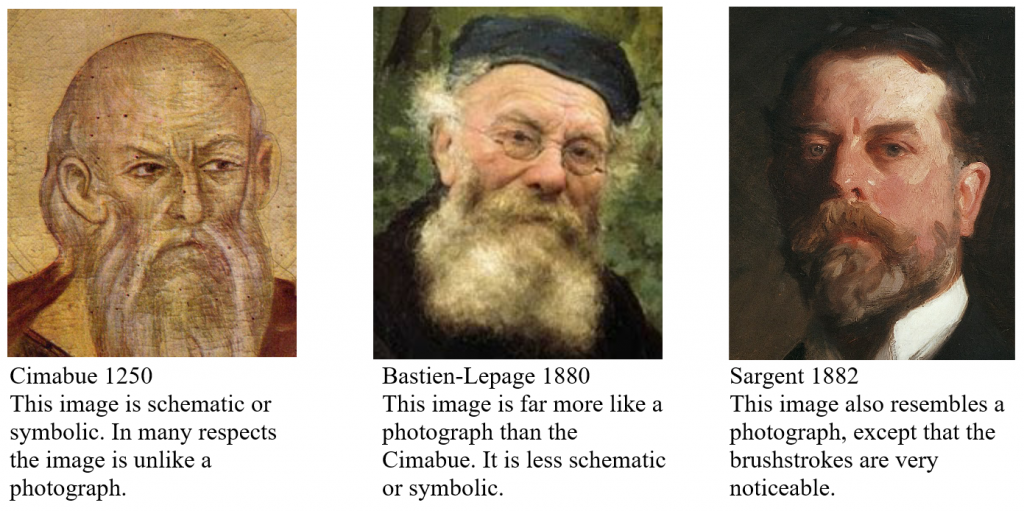

European Art of the period c1350 to c1880 is sometimes described as developing from the schematic works (of Cimabue for example) to the photographic works (of Bastien-Lepage for example). Some writers imagine that the intention of artists had always been to make the equivalent of photographs.

This is a gross simplification. Throughout this period artists paid great attention to interpretation – to the manner in which what is seen or imagined may be translated into line, form, tone and colour.

Often, when painters have come close to photographic accuracy they have not been satisfied, and have sought ways in which stop their paintings looking so photographic. Renoir returned to line, while others made their brushstrokes increasingly eye-catching.

PROGRESSION FROM SYMBOL. TO PHOTOGRAPH. TO EFFECT

Artist may make their pictures more and more like what might be seen in a static viewfinder. The picture gradually comes to look like a photograph, and the line disappears altogether.

At that stage, artists may wish to make the photograph more interesting by adding effects of one sort or another, or by returning to the lines which are the basis of representation.

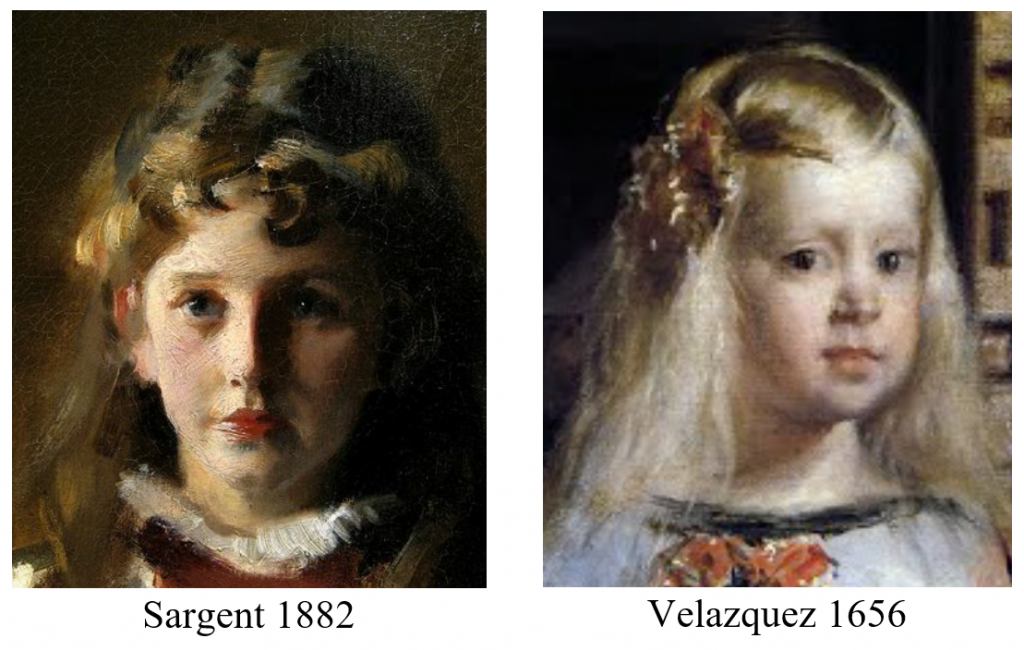

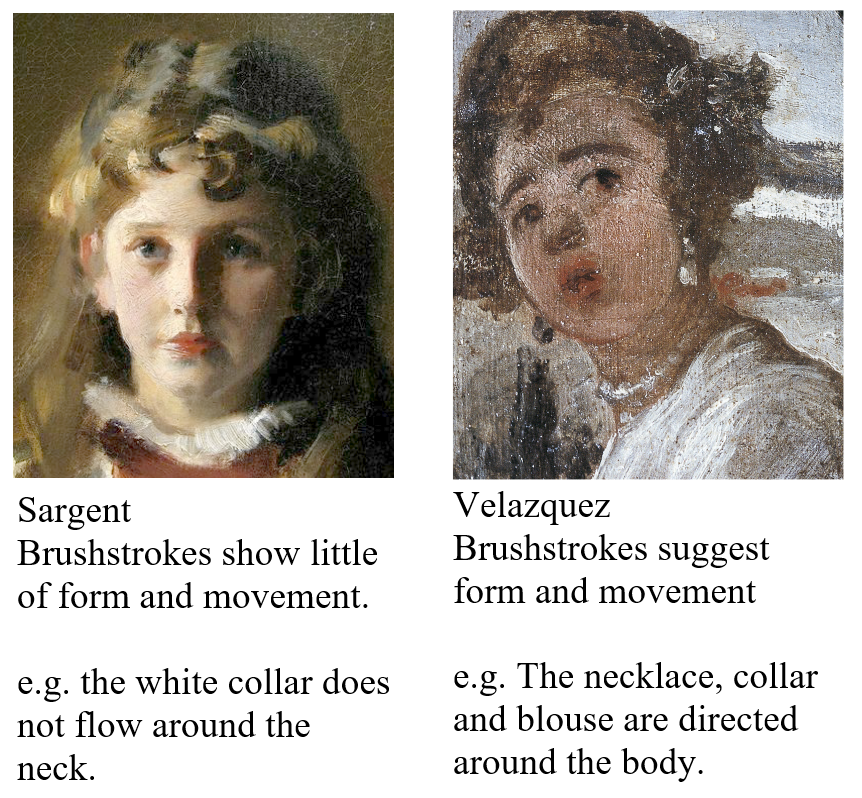

Painters like Bastien-Lepage came so close to photography that their works may sometimes be mistaken for coloured photographs. Other painters such as Sargent, made their works distinct from photographs by employing very noticeable brushstrokes.

With earlier painters, such as Velasquez, visible brushstrokes were a development of line – showing form and movement. With later painters, such as Sargent, visible brushstrokes were more like an effect applied to a static image – showing less form and movement.

Some, like Sargent, produced breathtaking results, but, by reducing line to such an extent (though not totally) they lost much contact with real life time and movement – the core of representation.

LINE AND OBSERVATION COMPLETELY OMITTED

Meanwhile, painters who use photographs as a substitute for real life tend to subdue photographic characteristics. Careful control of image processing can reduce excessive contrasts.

The artist can also apply his knowledge of real life, and so compensate for a number of photographic deficiencies. When the artist is highly skilled, with a well-stocked memory, the result can look as if painted from life or imagination.

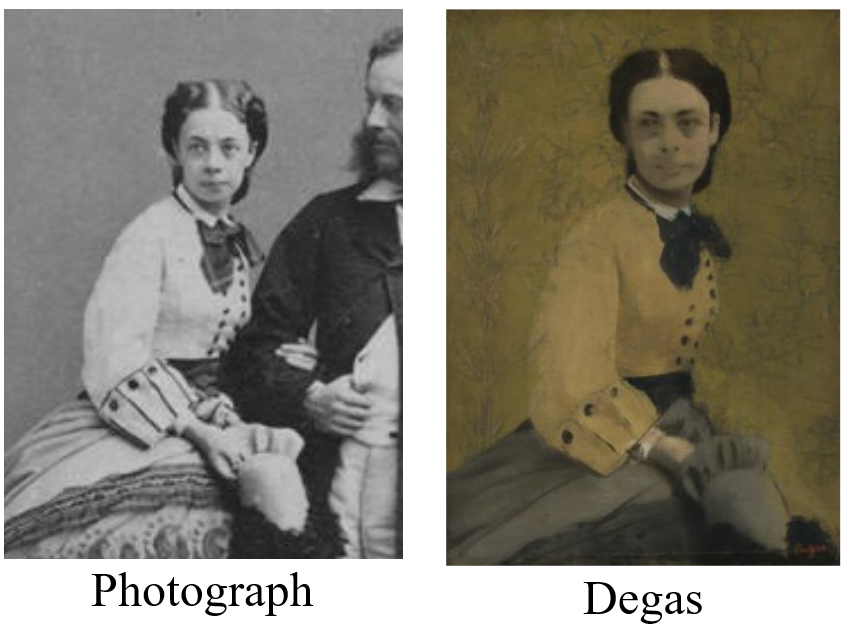

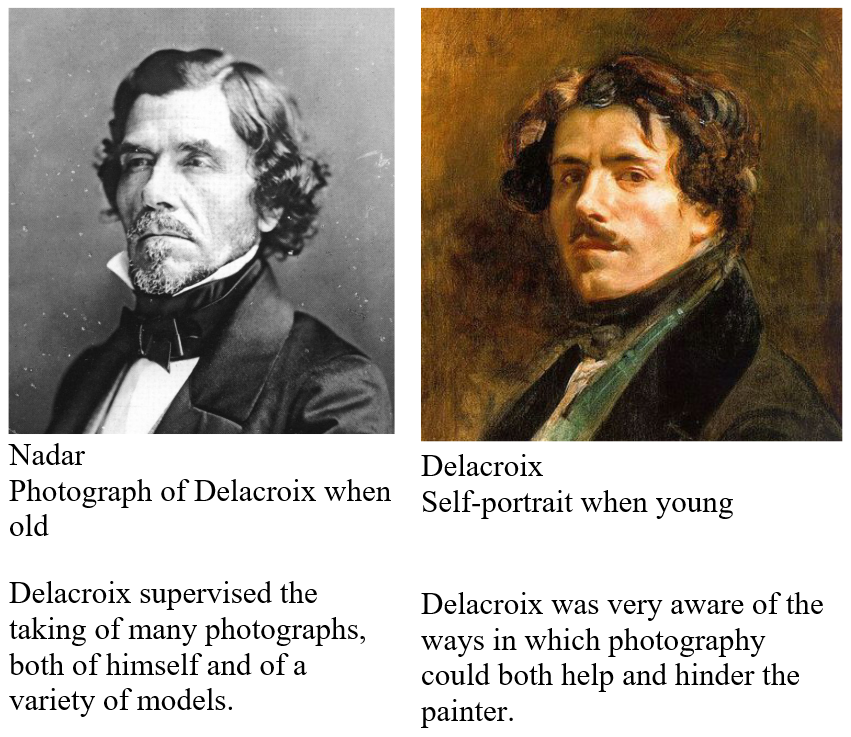

The sort of development, which was taken to an extreme by the photo-realists, had been foreseen by Delacroix – almost soon as soon as the daguerrotype had been brought to public attention, in 1839. He was very enthusiastic about the innovation (an early form of photography), but was also aware of its potential drawbacks. He wrote about painters of that period:

“The more they try to imitate the daguerreotype, the more they reveal their weakness. Their work then is only the copy – necessarily cold – of a copy, itself imperfect in other respects. In a word, the artist becomes a machine harnessed to another machine.”

The tendency to omit line, and to concentrate only on copying flat shapes results in what Delacroix described as coldness, a coldness which the photo-realists demonstrated to perfection many years later, making a feature of this characteristic..

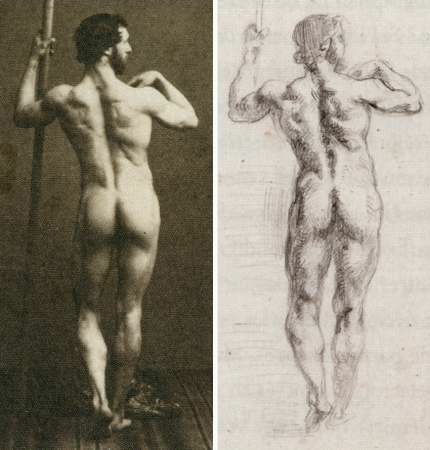

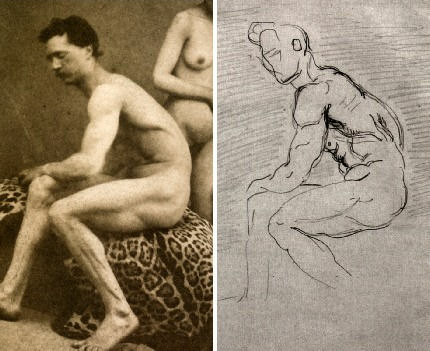

Coyping versus analysis.

In these drawings some of the lines show that Delacroix had been able to draw lines around the objects as if in real life, partly using some of his imagination.In other parts he relapsed into copying the light and dark, becoming only, “ A machine harnessed to another machine”.

This copying is never seen in his other drawings – almost certainly carried out entirely from life or imagination.

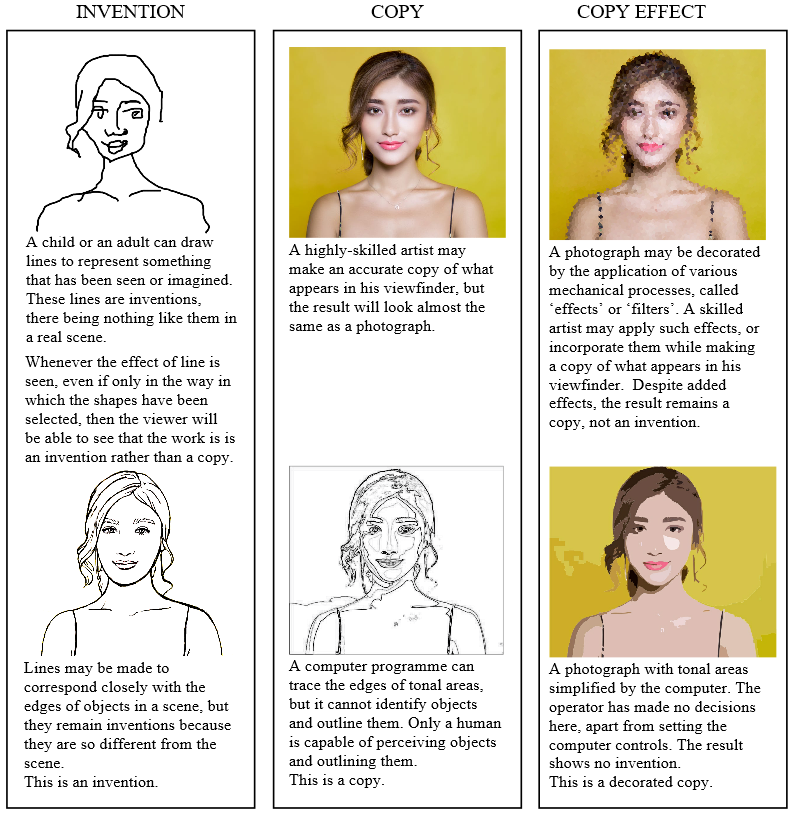

INVENTIONS VERSUS COPIES

INVENTIONS COMBINED WITH COPIES

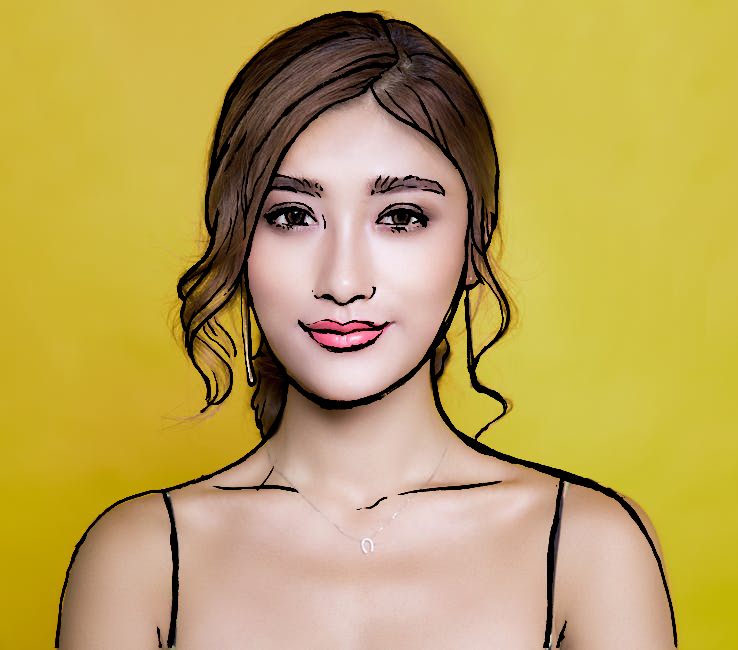

A painting combines lines and shapes (inventions) with elements of tone and colour derived from life or photography (copies).

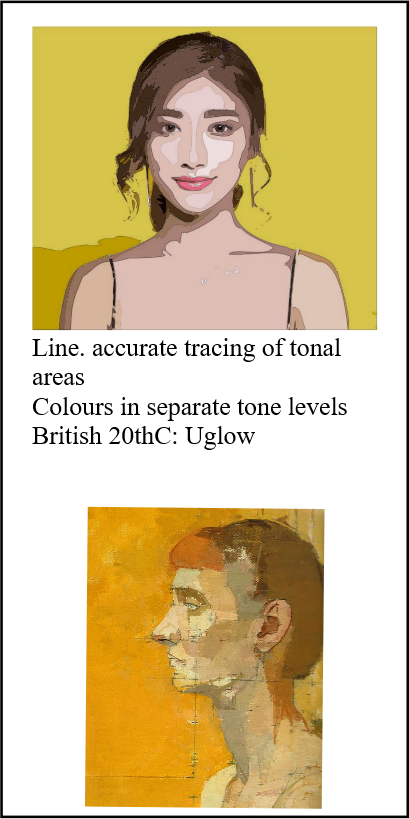

In the example below, colours and tones of the photograph are combined with drawn lines. On the next page there are more examples, exemplifying the infinite range of possibilities that such combinations present.

Making a painting which looks like a photograph demands enormous skill, but no invention.

In contrast, making a painting which represents a subject but does not copy it demands invention, even when done clumsily.

A child can invent, but a camera can only copy.

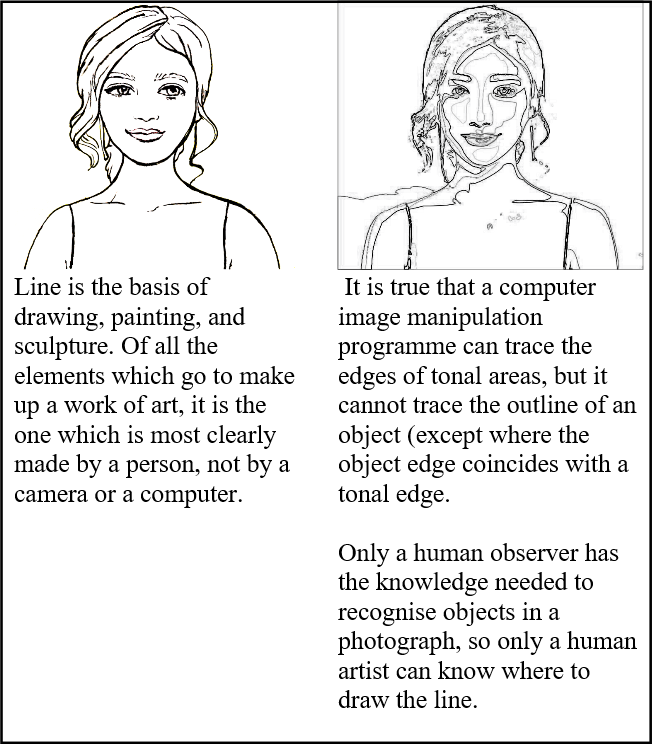

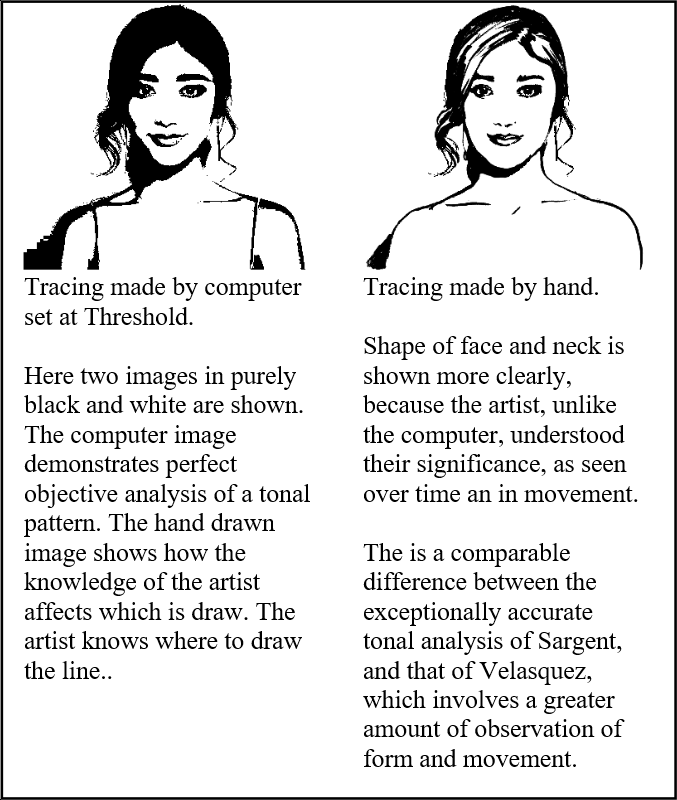

HUMAN VERSUS MECHANICAL ANALYSIS

With earlier painters, such as Velasquez, obvious brushstrokes were not simply records of of patches of colour. They were a development of line. They helped show form and movement. They derived from what could only be observed through time, not in an instantaneous photograph or the hand-made equivalent.

The brushstrokes of later painters, Sargent for example, show less of form and movement. By reducing line, such painters tended to lose contact with the essence of representation – with real-life time and movement.

However, by working always from life, such painters were bound to retain some sense of line. It was for later artists, the photo-realists, to go even further, and to totally eliminate all sense of line.

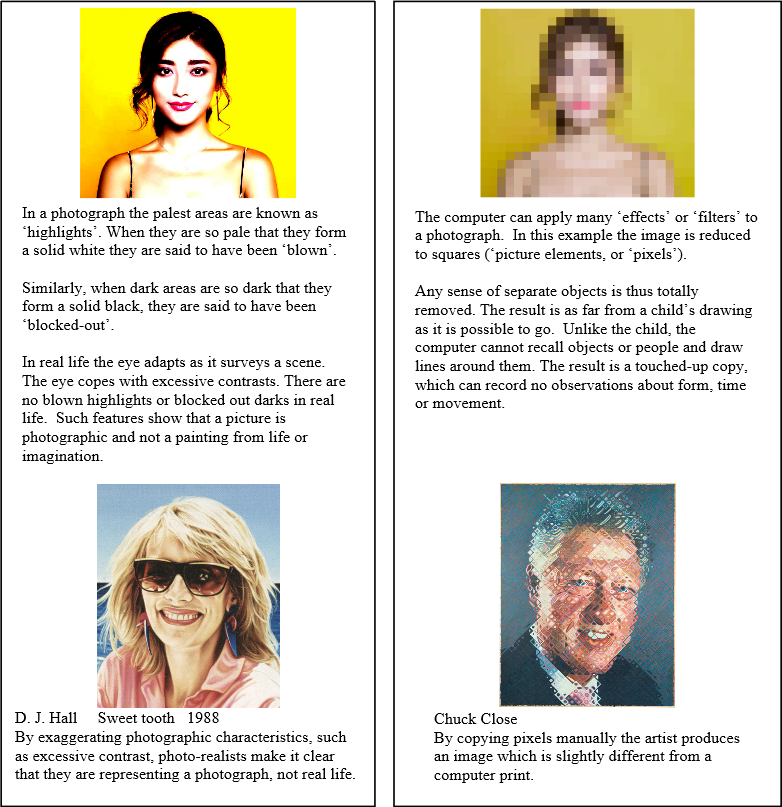

A great variety of such line-free effects is possible. Photo-realists literally copy photographs, thus totally eliminating any hint of a response to real-life time and movement. These works by D. J. Hall and Chuck Close’s show two amongst a range of photo-realist approaches.

PAINTINGS WHICH ARE DEVELOPMENTS OF INVENTED LINE

PAINTINGS WHICH RESEMBLE TOUCHED-UP PHOTOGRAPHS (At first sight)

FULLER DESCRIPTION OF THE STYLES DISCUSSED ABOVE