PAINTING WHAT YOU SEE.

Some writers make a distinction between a child’s drawing, which is held to be an expression of what the child KNOWS, and a photograph which demonstrates what the child SEES.

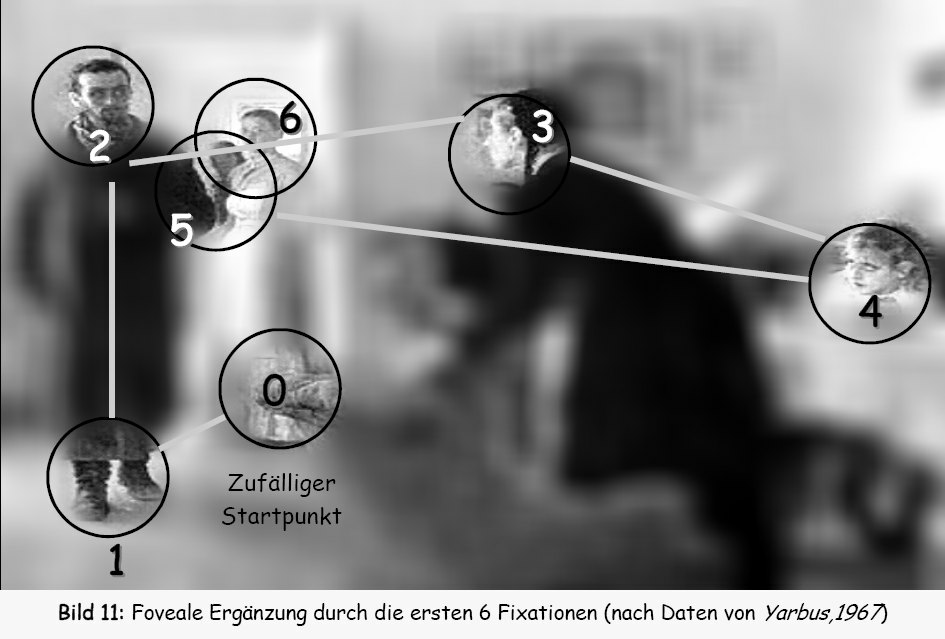

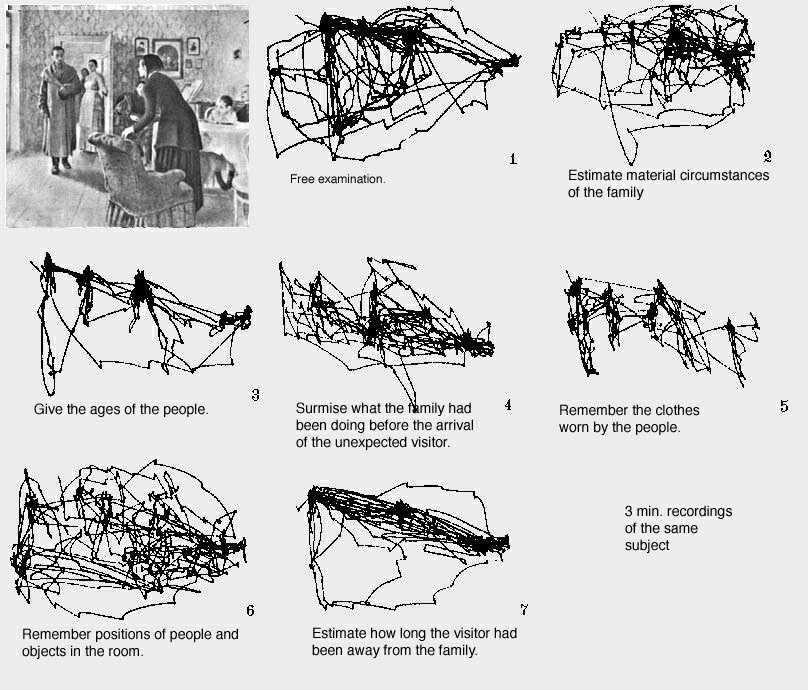

However the distinction between knowing and seeing is not as clear-cut as this might suggest. This is because the eye does not take in a scene at once, but scans it. When he advocated Naturalistic Photography, P. H. Emerson (1856 – 1936), believed that it would be possible to produce an image that was true to nature, in the sense that it would be true to what people really saw. However, as the diagram below shows, the eye moves so much that it would be impossible for a painting or a photograph to replicate these movements.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eye_movement

Arguably, in order to represent what the viewer sees, a sequence such as the one above should be presented, rather than the original picture.

However no-one would accept this as a depiction of what we really see. The viewer of that sequence would ideally read it, moving steadily from left to right. But that would never happen. The viewer’s eye would dodge about, just as eyes always do. Though the sequence may be an accurate record of what the original artist looked at, a viewer would never reconstruct the same experience based on a series of pictures like this.

Other attempts have been made to draw what we really see. Some say that this is what Picasso and Braque were doing in their cubist painting (although the artists themselves did not make this claim ). No matter how much these pictures may strike the imagination, no-one would seriously claim that they showed the world as it really appeared.

CUBISM NOT WHAT YOU REALLY SEE

1911, La Femme au Violon

Figure dans un Fauteuil (Seated Nude, Femme nue assise)

What we see depends on what we are looking for and the multiple messages sent from the eye to the brain and back again. In order to replicate our experience of seeing it would be necessary to replicate all these messages, and in some way provoke us into experiencing an equivalent sequence of messages. This, if it were ever to be a possibility, would require some sort of headset which could control the brain. The machinery required to do this would be quite unlike a painting.

But, while it is not possible to draw what we see, it is possible to draw what appears on a picture plane (what appears in a viewfinder). In other words, in principle, it is possible to replicate the pattern (or ‘array’) of light which was available to our eyes at a specific moment in time. Our eyes and brains might experience this in an infinite number of possible ways, and that experience cannot be displayed. Only the array of light can be displayed, usually in the form of a photograph – a duplication of the picture plane.

RUSKIN ON STEREOSCOPY

It may be thought that a 3D camera, one which produces stereoscopic photographs, might get closer to what we really see, and yet that idea, too, cannot survive a few minutes scrutiny.

Still Life: Vanitas 1965

Royal Academy of Arts, London© Royal Academy of Arts

As E. H. Gombrich explained:

A painting by Professor Lawrence Gowing, a passionate student of Cézanne’s visual researches, shows the artist carrying the Impressionist programme to its extreme. He has painted the still life as it appeared to him when he focused his eyes on a spot behind the table, thus producing the doubling of images of proximal objects and an apparent curvature of the table edge. We may say he has tried to produce a faithful map of his visual field at a given transitory moment and to enter on this map even the sensations we are usually set to ignore because they interfere with the perception of the external world.

Gombrich Mirror and Map, The Image and the Eye 1982

The great Victorian critic, John Ruskin (1819 – 1900) had considered a similar project as early as 1857.

PhotoMuse Collection, 2014

http://photomuse.in/

PRINCIPLE OF THE STEROSCOPE

John Ruskin, Elements of Drawing in Three Letters to Beginners, London 1857, appendix 1, note 1, p.42

I am sorry to find a notion current among artists, that they can, in some degree, imitate in a picture the effects of the stereoscope, by confusion of lines. There are indeed one or two artifices by which, as stated in the text, an appearance of retirement or projection may be obtained, so that they partly supply the place of the stereoscopic effect, but they do not imitate that effect. The principle of the human sight is simply this : by means of our two eyes we literally see everything from two places at once ; and, by calculated combination, in the brain, of the facts of form so seen, we arrive at conclusions respecting the distance and shape of the object, which we could not otherwise have reached. But it is just as vain to hope to paint at once the two views of the object as seen from these two places, though only an inch and a half distant from each other, as it would be if they were a mile and a half distant from each other. With the right eye you see one view of a given object, relieved against one part of the distance; with the left eye you see another view of it, relieved against another part of the distance. You may paint whichever those views you please ; you cannot paint both. Hold your finger upright, between you and this page of the book, about six inches from your eyes and three from the book ; shut the right eye, and hide the words * inches from ’ in the second line above this, with your finger ; you will then see ‘ six ’ on one side of it, and ‘ your ‘ on the other. Now shut the left eye and open the right without moving your finger, and you will see ‘ inches ’ but not ‘ six’. You may paint the finger with ‘ inches ’ beyond it, or with ‘ six ’ beyond it, but not with both. And this principle holds for any object and any distance. You might just as well try to paint St. Paul’s at once from both ends of London Bridge as to realize any stereoscopic effect in a picture.

So it is impossible to paint what we really see, because the eye is continually moving around and the brain is making calculations. But arguably it is these very calculations which prevent a total freshness. If only we could makes observations that were free of these calculations, perhaps then we would be seeing with the truly innocent eye?

It is sometimes thought that the ideal would be to be able to paint with the naïvety of a blind man who had just been given sight. Gombrich explained in Art and Illusion how this approach seemed to be a real possibility to most theorists in the 19th century.

…To Ruskin… it is our knowledge of the visible world that lies at the root of all the difficulties of art. If we could only manage to forget it all, the problem of painting would become easy — the problem, that is, of rendering a three-dimensional world on a flat canvas. In reality, Ruskin thought, we do not even see the third dimension. What we really see is only a medley of coloured patches such as Turner paints.

Gombrich – Art and Illusion – Part Four: IX section II

Ruskin’s presentation of this theory, written in 1856, anticipates the doctrine of the impressionists:

“The perception of solid Form is entirely a matter of experience. We see nothing but flat colours; and it is only by a series of experiments that we find out that a stain of black or grey indicates the dark side of a solid substance, or that a feint hue indicates that the object in which it appears is far away. The whole technical power of painting depends on our recovery of what may be called the innocence of the eye; that is to say, of a sort of childish perception of these flat stains of colour, merely as such, without consciousness of what they signify, — as a blind man would see them if suddenly gifted with sight.

“For instance: when grass is lighted strongly by the sun in certain directions, it is turned from green into a peculiar and somewhat dusty-looking yellow. If we had been born blind, and were suddenly endowed with sight on a piece of grass thus lighted in some parts by the sun, it would appear to us that part of the grass was green, and part a dusty yellow (very nearly of the colour of primroses): and if there were primroses near, we should think that the sunlighted grass was another mass of plants of the same sulphur-yellow colour. We should try to gather some of them, and then find that the colour went away from the grass when we stood between it and the sun, but not from the primroses; and by a series of experiments we should find out that the sun was really the cause of the colour in the one,— not in the other. We go through such processes of experiment unconsciously in childhood; and having come to conclusions touching the signification of certain colours, we always suppose that we see what we only know, and have hardly any consciousness of the real aspect of the signs we have learned to interpret. Very few people have any idea that sunlighted grass is yellow. . . .

We remember that the ideas about perception on which Ruskin built with such confidence, and artistically with such success, had been propounded more than a century earlier by Bishop Berkeley in his ‘New Theory of Vision’ (1734) in which a long tradition had come to fruition: The world as we see it is a construct, slowly built up by every one of us in years of experimentation. Our eyes merely undergo stimulations on the retina which result in so-called “sensations of colour.” It is our mind that weaves these sensations into perceptions, the elements of our conscious picture of the world that is grounded on experience, on knowledge.

Given this theory, which was accepted by nearly all nineteenth-century psychologists and which still has its place in handbooks, Ruskin’s conclusions appear to be unimpeachable. Painting is concerned with light and colour only, as they are imaged on our retina. To reproduce this image correctly, therefore, the painter must clear his mind of all he knows about the object he sees, wipe the slate clean, and make nature write her own story— as Cézanne said of Monet: “Monet n’est qu’un oeil — mais quel oeil!”

(Monet is only an eye, but what an eye!)

KOHLER – RELATIONSHIPS NOT ABSOLUTES

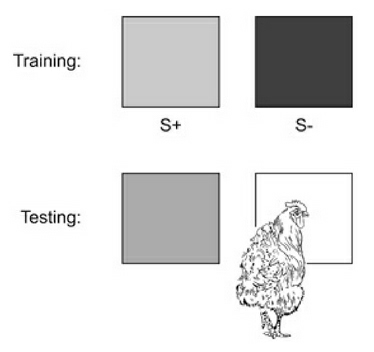

This idea of the blind man who has been gifted with sight makes it sound as if his eye were a sort of light meter or colorimeter, so that he could point it at a patch of colour, record that colour in his mind, and then reproduce that exactly colour on his painting (or even simply select it from a colour chart). However this theory is mistaken, as the following experiment demonstrates.

Learning & Behavior: Eighth Edition p237

By James E. Mazur 2016

The psychologist, Edward Thorndike (1874 – 1949) was among those persuaded by the ‘innocent eye’ theory of Ruskin and the French Impressionists – that the eye perceived exact colours. He believed that animals learned to respond to a particular stimulus with a specific response. However Wolfgang Köhler (1887-1967), a German-educated American psychologist, was able to show that that was not how chickens responded.

When presented with a grey and a dark-grey card, chickens could be trained, after many repetitions, always to peck at the dark-grey card. They had learnt to expect a reward of a few grains of food. Thus it looked as if Thorndike had been right – a certain stimulus (the dark-grey) would produce a certain response (the pecking). Similarly it might be said that artists, given a certain stimulus – dark-grey, would produce a certain response – a matching area of dark-grey paint. The observation of the dark-grey enters the brain, is stored, and then is brought out again when appropriate.

However, when Köhler presented the chickens with the same dark-grey, but this time next to a black card instead of a mid-grey card, the chickens did something unexpected. They did not peck at the dark-grey : instead they pecked at the black. Evidently they had learnt to respond, not to a specific grey, but to a relationship. They had learnt to peck at the darker of the two cards.

The idea of the innocent eye is that all that stops us from observing colours directly are ideas which are already in our head. These expectations or pre-conceptions allegedly distort the way in which we classify the coloured patches which have appeared in front of us. For example we know that blond hair is yellow, so that is how we tend to paint it, even though a careful examination of the image in the viewfinder would reveal that blond hair was really made up of patches of dull brownish grey. With training, artists can learn to observe and match these subtle colours, but this does not mean that their eyes have been restored to a state of innocence. Rather they have learnt a series of mental procedures or tricks which enable them to examine these patches of subtle colour in relationship to the colours which surround them. When painting they construct a complex pattern of colour relationships, not a direct matching of the scene.

Even if the artist sets himself to copy the scene using the palette-knife method described by the Hon. John Collier (See above) the painting will still not match the scene correctly, because, for example, the highlight on a piece of jewellery will be far too bright to be matched. As we saw with high-dynamic range photography, even the most determined copyist will eventually be forced to look at relationships. Artists and chickens alike are born looking for relationships, not colours in isolation.

So these factors indicate that the innocent eye is a myth:

1. that eye movements cannot be replicated in a painting or a photograph

2. that stereoscopic vision cannot be replicated, and

3. that colour perception depends on relationships, not direct matching,

the idea of the innocent eye persists.

However the theory of the Innocent Eye is still believed by many artists. It proves to be an impediment to the full development of representational painting.