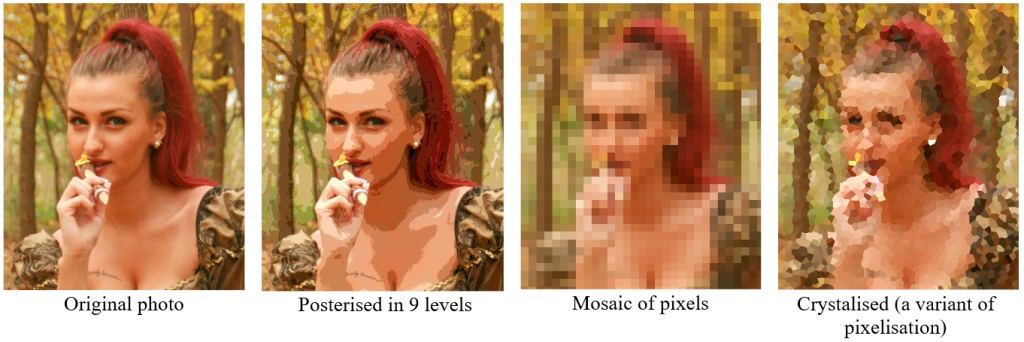

A computer can simplify a photograph in such a way that, at least at first sight, it may look just like an Impressionist painting.

These effects can be very convincing, so much so that a friend who converted some photographs using a ‘watercolour’ filter was highly praised for his painting technique, even though he had only tapped on the computer keyboard.

The ‘Crystalise’ effect (at the far right) can imitate oil brushstrokes, and some programmes allow this to be done with great subtlty. But, even though such results can be deceptive, they differ from genuine paintings in important respects. These will be discussed in the rest of this chapter.

IMPRESSIONISM AND PHOTOGRAPHY COMPARED

Entrée du village de Voisins, 1872

A perfect example of a French Impressionist painting

A casual observer may be duped by the sort of manipulations shown at the start of this chapter. To an extent, this demonstrates that Impressionism is less a style than an effect – a set of mechanical rules which can be applied to the image-in-the-viewfinder. It would be much more difficult for a computer to simulate the Baroque style, say, or that of the high Renaissance, in which the shapes are very different from the shapes as seen in a viewfinder, not just simplifications of them.

This is not to deny that the great French Impressionists did more than apply an effect. A careful viewer will see many examples of schematisation – of drawing lines, albeit with paintbrushes loaded with paint. But the fact that the casual viewers can be deceived so easily does show how close Impressionist paintings are to photographs.

This may be the reason why the Impressionist approach has persisted for such a long time – 150 years or so. Other styles, such as those of Michelangelo or Rubens, say, require that the artist be able to call on much greater mental resources – a profound understanding of perspective and anatomy, for example, not to mention a well-trained visual memory. French Impressionism at its most basic does not require much memory and imagination – just the ability to convert the scene into coloured patches.

Like photographs, Impressionist paintings are sure to please viewers because of their striking truth to nature. Everyone can feel pleasure at the shock of recognition that such pictures provide, along with the fascinating experience of seeing apparently meaningless blotches of paint cohere into the depiction of recognisable subjects, when viewed at the appropriate distance.

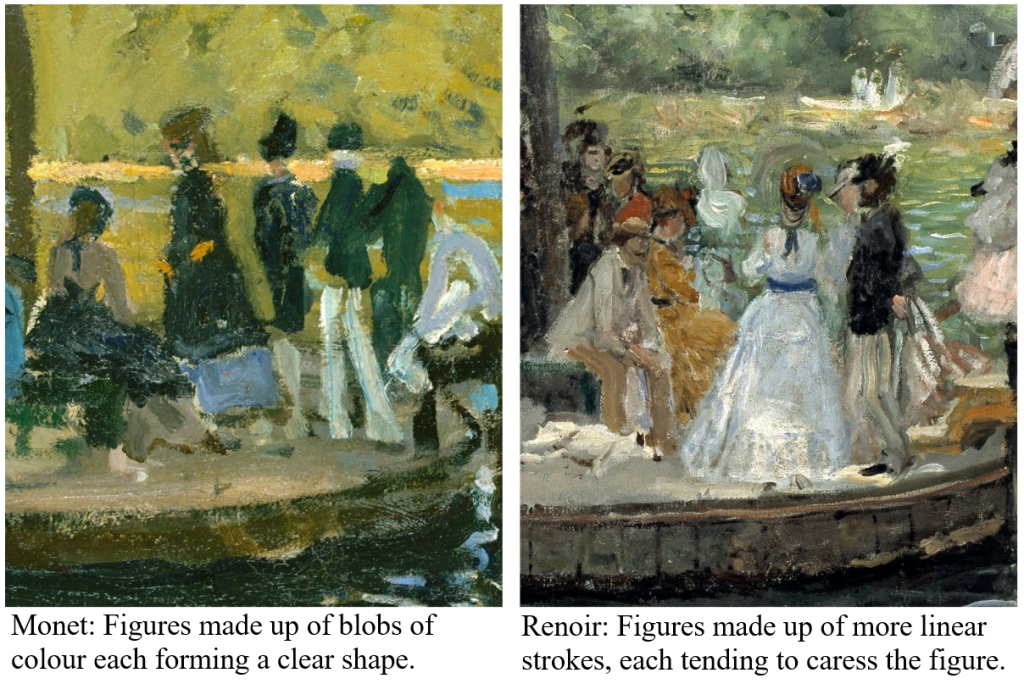

The stylistic differences between individual Impressionists are similar to the so-called stylistic differences between photo-sensitive materials. Films have individual characteristics – exaggerating certain colours for example – so a photograph taken on Kodachrome 25 film, say, looks very different from one taken on Fuji Reala film. Painters also have individual characteristics – not only in colour bias, like different films – but also in brushwork (in their so-called ‘handwriting’). Most importantly, painters differ in the character of their drawing, something outside the realm of photography. This is seen clearly when different artists have painted the same scene. (See the paintings by Monet and Renoir, below)

A very large number of painters have followed the lead that the original Impressionists gave in the 1870s, and have produced thousands of paintings in the Impressionist mode; but very few of these pictures have come close to rivalling the quality of those made by Monet, Renoir, Pissarro, Sisley and one or two of their fellow painters. Those pioneers had a fuller sense than their followers of the subtle grouping of colour and shape – in a word, drawing. They had studied drawing from a classical point of view, and brought this wider understanding to the task of duplicating shapes presented in nature. This feeling for drawing has proved impossible for anyone to imitate who has aimed only at duplicating the image-in-the-viewfinder. A better-stocked mind is needed. The great Impressionists subtly modified the image with linear qualities which are impossible for a computer to add. For example, the figures in the Monet, shown below, are depicted with strokes of paint which give a sense of direction and movement – something which would not emerge from a photograph however much it was filtered by a computer.

Even so, lines are relatively minor components of the Impressionist approach. Its main characteristic is its truth to nature (meaning its accuracy in duplicating the image-in-the-viewfinder). Since the subject in the viewfinder may equally well be pleasant as unpleasant, it made sense to choose pleasant subjects. French Impressionism, with its concentration on pure shape and colour, lays emphasis on the experience of the moment rather than on the passage of time which forms such an important element in previous styles. This is why Impressionism has been called the painting of happiness.

However there has always been a feeling that this carefree lack of style left something to be desired. This seems to have been why Pissarro and Renoir gave up painting in the Impressionist mode. Monet persisted with it, but exaggerated the characteristics of the effect, rather than enlarging the style’s visual vocabulary, or employing it in a different way. He became what Sickert described as a ‘doctrinaire Impressionist’. Only Sisley was content to carry on in the Impressionist mode for the rest of his life.

FROM CLASSICAL TO IMPRESSIONIST

When the Impressionists interpreted the image-in-the-viewfinder as a combination of flat patches of colour, painted with clearly visible brushstrokes, they were not departing very far from what previous painters had done. What surprised the critics was that the Impressionists were presenting what appeared to be sketches as if they were finished paintings.

MONET versus RENOIR

It has been a theme of this book that the theory and practice of French Impressionism had much in common with that of Naturalistic Photography. But the artists were not merely hand-made naturalistic photographers. What the painters achieved could only have been done with painting. Perhaps the simplest way to demonstrate the nature of this achievement is to look closely at the work of two of the greatest painters of the movement, Monet and Renoir. As luck would have it, they painted side-by-side in 1869 and so have left two paintings which may be compared and contrasted directly.

Note: La Grenouillère (literally the ‘Frog Pond’) was a café and bathing establishment at Croissy-sur-Seine, 20 minutes train-ride from Paris. “Frog” was a slang expression for a young woman, rather as one might say ‘chick’ or ‘bird’ in English. The resort became fashionable in the 1860s, and it attracted numerous articles in the press. The visitors ranged from artists and writers to aristocrats. Napoleon III and Empress Eugenie visited in July 1869, the same year as when Monet and Renoir painted there, with easels side-by-side.

Monet painted three canvases, and Renoir painted two. These five paintings represent the beginning of French Impressionism, and show the approach arguably at its most characteristic.

At this point in time, Monet and Renoir’s painting styles were more similar than they ever were before or since; but, while both reduced the scene to a pattern of coloured shapes, differences in temperament between the artists show up clearly. This is particularly noticeable in details:

Even though they were looking at scenes-in-the-viewfinder which were almost identical, Monet and Renoir differed in what they selected to paint, brushstroke by brushstroke. They were not simply duplicating what appeared in the viewfinder. They were searching and analysing.

When writing about the development of Fremch Impressionism, Kenneth Clark described the contrasting artistic characters of Monet and Renoir:

The stages in this development are clearly marked. It begins in 1869 with the closer friendship of Monet and Renoir, one of those conjunctions, like that of Coleridge and Wordsworth, from which new movements in the history of art are often born.

Monet had always been the member of the group who trusted most unreservedly to visual sensations, and with whom the traditions of European painting carried least weight.

Whereas his companions were devoted students of the old masters — Manet and Cézanne both made admirable copies and Degas was perhaps the finest copyist who has ever lived — Monet could find nothing to interest him in the Louvre. He was taken there forcibly by Renoir, who himself saw no reason why he should not continue the tradition of Watteau and Fragonard, given sufficient skill and application.

Renoir had very great skill, as we can see from his early portraits, and his apprenticeship as a china painter had taught him a fresh and brilliant technique. No muddy colours, no dark shadows, no rich impasto were possible on porcelain.

Renoir was at first too intent on the eighteenth century to join in the unquestioning approach to nature. His early landscapes are more like Diaz than Daubigny. But in 1869 he began to work with Monet on the same motive, and from this union impressionism was bom.

Monet contributed his complete confidence in nature as perceived through the eye and his remarkable grasp of tone ; while Renoir contributed his brilliant handling and rainbow palette.

Page 91

Landscape into Art (1952)

by Kenneth Clark (1903-1983)