We have seen how European and Mediterranean artists started by making schematic pictures and only after a long struggle were they able make pictures that were more impressionist or photographic. (See the illustration below). But some people have suggested that this struggle can be by-passed. They suggest that an artist blessed with a so-called ‘photographic’ memory might be able simply to copy out his or her memory onto the page or canvas.

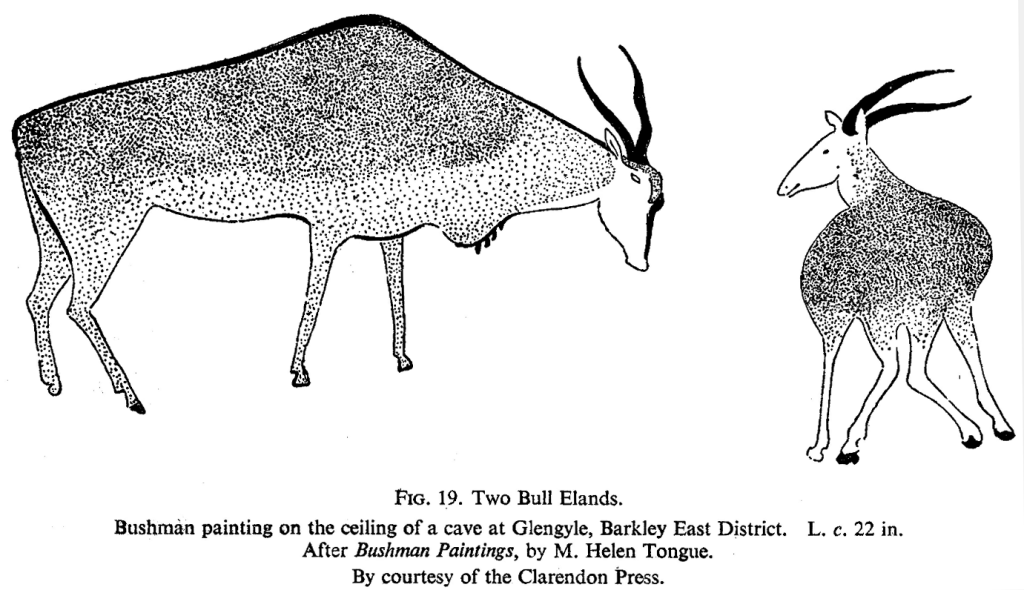

It seems unavoidable that a long struggle had to take place in order to reach the almost pure objectivity of the approach shown in Dürer’s woodcut. Even today’s students, who have the advantage being able to look back on pictures made during the past few centuries, still have to engage in a personal struggle in order to learn how to observe shapes. As we shall see in the next section, the Bushman artists seem to have been able to by-pass this learning process, and to go straight for delineating shapes.

PHOTOGRAPHIC MEMORY IN FACT AND FICTION

Some years ago the astonishing work of a young autistic boy, Stephen Wiltshire MBE (1974 – ), formed the subject of many films and television programmes. He was able to draw the most complicated architectural drawings from memory, after having looked at a scene for only a few minutes. He has gone on to a successful career as an architectural artist. Naturally there was much speculation about how he had been able to perform such feats.

Stephen Wiltshire seemed to be demonstrating a type of memory called “eidetic”, in which the individual can observe and recall exact shapes for a few minutes, or even longer. Eidetic memory (from Greek eidetikos “pertaining to images,”) occurs in a small number of children but few retain it into adulthood.

One use of the term, “Photographic memory”, in contrast, is not concerned with shapes, but with capturing and retrieving pages of text or numbers in great detail. In the comedy film Carry on Spying (1964) Barbara Windsor’s character was able to memorise complicated documents simply by staring at them for a fraction of a second and then closing her eyes like a camera shutter. Unlike eidetic memory, this type of memory has never been demonstrated to exist.

Robert Catterson-Smith (1853-1938), the expert in mind-picturing, remarked that drawing from memory was drawing from stored observation. The artist recalls a series of mental actions – observations about position and direction. It is an active process. The artist has to make these observations before they enter the memory. This is different from passively recording a mental image, as a camera records a snapshot.

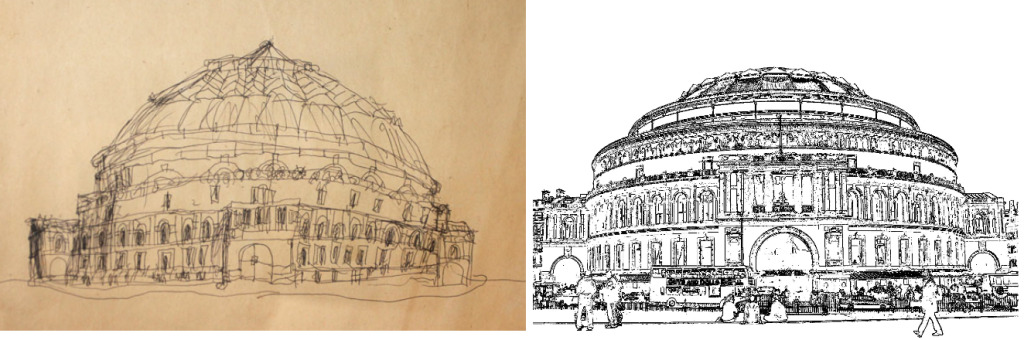

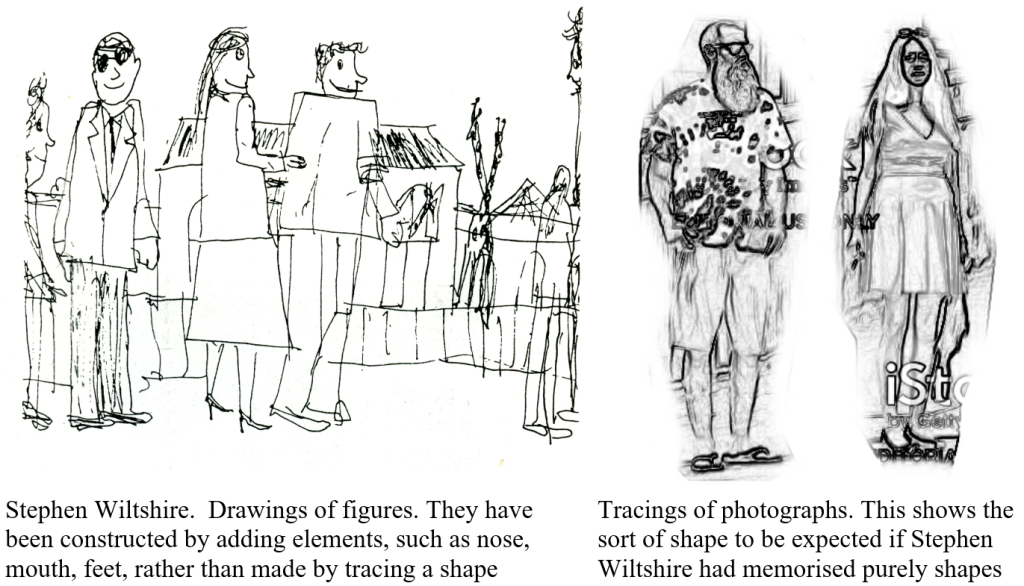

The accurate perspective of Wiltshire’s drawings suggests that he observes pure shape, but his lines do not show the edges of tonal areas, such as cast shadows, which they would do if he were simply tracing a memory-image in the way that a computer traces a photograph. His lines show the boundaries of distinct architectural features. This demonstrates that he analyses the objects he draws. He does not simply copy light and dark. His drawings are representations, not duplicates.

This is shown perhaps even more clearly in his drawings of figures. In these, the constructive elements are shown: body, head, nose, mouth, legs. This is very different from the tracing of the shape of a figure. Wiltshire’s concepts determine which shapes he will examine. However, as Catterson-Smith himself pointed out, the process of recalling observations does help to form a picture in the mind, and that mind-picture in turn can help call up further memories of stored observations. So eidetic memory and stored observation can work together.

The average student has to overcome a tendency to make each line represent a word – eyes, nose, mouth for example. The time which students take to learn how to ‘reduce the round to the flat’ can vary from a few minutes to many hours. Perhaps the quick students are more talented, or perhaps their feeling for shape is stronger than their feeling for words – though both shape and words may be involved at the same time. In contrast, Stephen Wiltshire has an exceptional capacity to observe the shapes of objects much more readily than the average student. Is it possible that his mind is less obstructed than that of the non-autistic student?

In his essay on the art of the Bushmen, the art critic, Roger Fry (1866 – 1934) reflected on the possibility that the Bushmen similarly had minds that were less obstructed than those of the average European. (I have included some excerpts from his essay on the following pages). Fry noticed that, although very simple and crude, the paintings of the bushmen were extraordinarily accurate records of observed shapes. Even the paintings of stone-age people in Europe are inferior to Bushman paintings in this respect (being more schematic), even though they may be more accomplished artistically. Paintings made by the ancient Egyptians and Greeks are even more schematic than those of their stone-age ancestors. Fry suggested tentatively that the more civilised people became, the more they needed to pay attention to concepts – to words rather than shapes. Their thinking became more abstract or intellectual. It seemed as if this intellectual thinking had impeded their ability to observe shapes.

As far as I know, no psychological studies have been made which investigate whether, say, subjects who become more skilled at mathematics and literature (conceptualisation), lose some of their ability to draw shapes (impressionism). A hint of an answer was given in an essay introducing the drawing made by the Stephen Wiltshire. His teacher, Lorraine Cole, remarked that, “Some children, with similar difficulties to Stephen, lose the drive to draw when other forms of communication open up for them.” (Page 9 ‘Drawings, Stephen Wiltshire’ 1987).

This illustrates how giving a name to a shape (stimulus figure) can influence how it is recalled. The words on the left lead to the shape being recalled as at the far left. The words on the right lead to the shape being recalled as at the far right. So the word attached to a shape can make a great difference to the way in which it is observed and recalled. Is it possible that words impede the observation of shape?

CONCRETE TO ABSTRACT THINKING

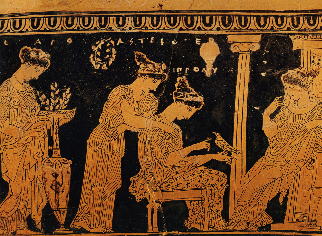

A Victorian painting of ancient Greeks, but less schematic that the Greeks would have made themselves. The heads are not in such strict profile. The position of the limbs is not so clearly displayed.