The Innocent Eye has made frequent appearances in this book so far, and it might be worth summarising the theory, especially from the point of view of a practical painter or art-lover, who may not see the theory in quite the same way as a psychologist or an art historian.

Three explanations may be taken as examples:

1. John Ruskin (1819 – 1900),

2. Claude Monet (1840 – 1926) – as recalled by Sargent- and

3. Roger Fry (1866 – 1934).

All of them were painters, though Ruskin and Fry are better known for their writings than for their pictures. It is not clear that any of them really thought through the subject with the sort of scientific intensity with which Gombrich called on when he mentioned psychologists like Gibson, Thorndike, and Kohler.

It is possible that Ruskin and the others were being a little too grandiose when they spoke of the innocent eye and the image on the retina. In practice, what they were talking about was making a copy of the picture plane. As Monet expressed it:

“When you go out to paint, try to forget what objects you have before you, a tree, a house, a field or whatever. Merely think here is a little square of blue, here an oblong of pink, here a streak of yellow, and paint it just as it looks to you, the exact color and shape.”

What Monet advocates here is not revolutionary. It is very much in line with what artists had been advised to do since the seventeenth century, and probably many centuries before. Monet was just being more extreme in not finishing as much – nor blending the tones, and in not aiming to give a sense of the three-dimensional. In Gombrich’s terms, Monet keeps clearly towards the impressionist end of the schematic/ impressionist scale.

These days, the theory of the “innocent eye” plays a major part in the training of most representational painters. Some even consider that drawing from life with near photographic accuracy constitutes the essential grammar of representational art. Such rudimentary training is certainly valuable, and was advocated by Sir Joshua Reynolds (1723-1792), and by William Hogarth (1697- 1764) before him. But this is not what Hogarth meant by grammar.

As we have seen, Hogarth considered copying to be essential training for a beginner, but continuing to copy for years on end, even from nature, was not the same as developing what he meant by a grammar of art – a collection of ready-made combinations of shapes and forms At most periods, drawings were not make by artists whose eyes were innocent. Quite the opposite. They were made by artists whose eyes had been thoroughly trained in memorising the drawings of their masters, and then by developing new variations and combinations, often as the result of careful comparisons of what they observed for themselves with what they had learnt. The traditional artist’s eye was neither innocent, nor ignorant. It was thoroughly knowledgeable. It was formed, not be rejecting preconceptions, but by developing them and by forming them into very extensive visual vocabularies.

We saw in an earlier chapter how teachers have devised ways in which to help the student replicate the shapes and colours which would appear on a pane of glass, or rather, on an imaginary picture-plane. These methods involve disrupting the process of recognition, for example by observing the scene upside-down, or with some of it covered over. In this way students can learn to concentrate more on areas of colour and tone than on the objects which they might recognise. Some even call the training which such students undergo, “learning to see”. This sounds as if a god-like power has been imparted. In reality the student has not been taught to see, but rather taught how to follow a set of rules for making observations, rules which differ from those normally used in day-to-day observation. When walking down the street, for example, artists tends to notice and avoid obstacles in just the same as anyone else. It is only when they switch to picture-making mode that they make observations in this ‘Innocent Eye’ manner.

While this kind of training is excellent for its purpose (reducing the scene to flat shapes), it can be an impediment when it comes to observing in other ways. For example in the type of drawing carried out in the Renaissance, by Raphael, say, the artist draws lines around ideas of solid objects (cylinders, spheres and cones). A human figure is thought of as being constructed out of these relatively simple geometrical objects. Artists trained exclusively in Innocent Eye mode will copy the light and dark in the subject in front of them completely missing this level of analysis. Far from having learnt to see, they have learnt to become blind to solid objects and to the way in which they move through time and space.

So there are two main schools of thought,

1. the artist should only learn the basics of copying – which are relatively easy and rapid to acquire. (In the 18th Century this would often have been taught at age 9, 10 or 11), or

2. the artist should progress to the constructive approach, which requires a great deal more thought (in the 18thC this would often have been taught along with the basics at 10, 11, or 12).

By the 19thC, art training had become largely the province of art schools, attended by children of the professional classes, and so the training, such as it was, began much later than in earlier times. No longer were boys and girls being taught, but young men and women – whose minds were already hardening and less able to pick up vast amounts of knowledge.

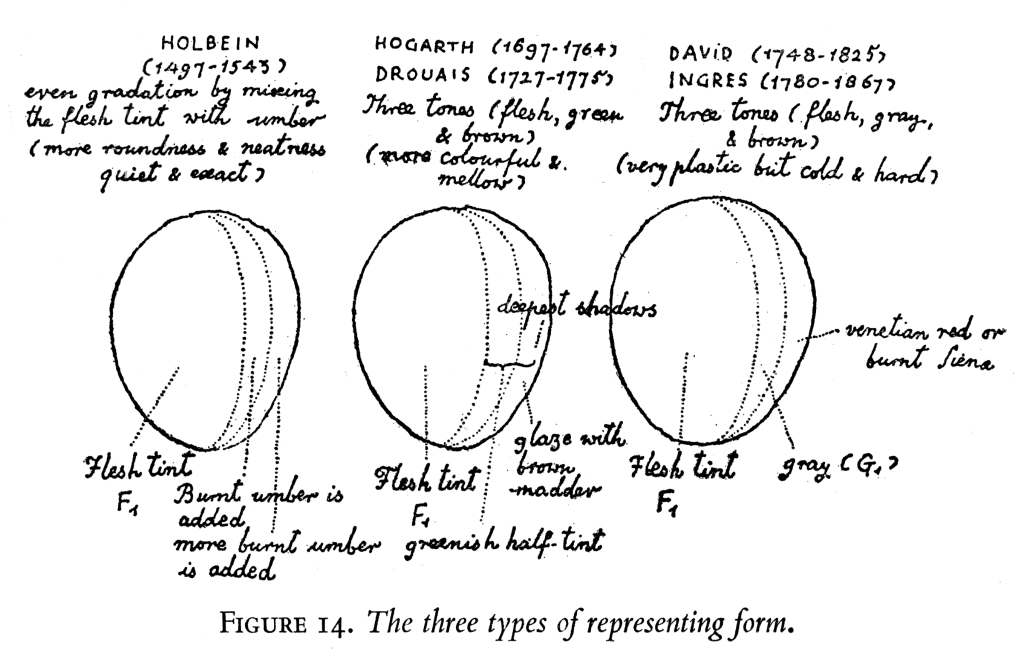

The Practice of Painting (1948)

This illustrates how the subject would be split up into areas of tone according to the volumes (in this case egg shaped volumes). This is different from splitting up purely according to tone values (‘posterisation’). In this way, from their earliest days of training, young artists would learn both to split up the visual array as Monet was suggesting, but at the same time learn to construct according to the principles of classical drawing.

ROGER FRY – AND THE INNOCENT EYE

E H Gombrich in Art and Illusion described the opinion of Roger Fry:

E. H. Gombrich:

….artists such as John Constable, who strove to be true to his vision, still had to admit that no art is ever free of convention or of what Constable called ‘manner’. It is these conventions, we remember, which enable the art historian to date a work such as Constable’s Wivenhoe Park despite its apparent truthfulness; it is their totality which makes up what we call ‘style’ in painting.

In returning to this problem, we cannot do better than to consider a passage from Roger Fry’s Reflections on British Painting which is concerned with Constable’s place in history.

Wivenhoe Park, Essex, 1816

Even though this painting is exceptionally naturalistic (or photographic) it still has a clear style. An historian (or even a keen art-lover) could easily date it to within a few years of its its creation, simply based on its use of schemata (such as the way in which the trees are simplified).

Roger Fry:

‘From one point of view the whole history of art may be summed up as the history of the gradual discovery of appearances. Primitive art starts, like that of children, with symbols of concepts. In a child’s drawing of a face a circle symbolizes the mask, two dots the eyes, and two lines the nose and mouth. Gradually the symbolism approximates more and more to actual appearance, but the conceptual habits, necessary to life, make it very difficult, even for artists, to discover what things look like to an unbiassed eye. Indeed, it has taken from Neolithic times till the nineteenth century to perfect this discovery. European art from the time of Giotto progressed more or less continuously in this direction, in which the discovery of linear perspective marks an important stage, whilst the full exploration of atmospheric colour and colour perspective had to await the work of the French Impressionists. In that age-long process Constable occupies an important place.’

E. H. Gombrich:

Roger Fry’s explanation of the sway of conventions in art is based on the old distinction between ‘seeing’ and ‘knowing’ which can be traced back to classical antiquity. It is a distinction which would not have retained its popularity with artists, critics, and teachers had it not proved extremely handy to all those who want to discuss the problems of representation and the mistakes beginners are likely to make. In this terminology the image which relies on ‘knowledge’ only is ‘purely conceptual’, and the history of art, as we have seen, becomes the history of the expulsion of this intruder.

Roger Fry considered the work of the Bushmen of the Kalahari desert to be the exception to his rule. Their outlines he considered to be so much closer to ‘seeing’ than ‘knowing’. It was as if their minds held fewer of those pre-conceptions which hindered Europeans when they went in quest of innocent observations.

GOMBRICH ON THE INNOCENT EYE

Gombrich contrasted the innocent eye with the probing eye. Our eyes and brains seek out and respond to relationships between light messages, rather than to the messages themselves. We are made to perceive relationships rather than absolutes.

Gombrich illustrated this by referring to Kohler’s experiment which we looked at in the last chapter.

The capacity of our minds to register relationships rather than individual elements.

Art and Illusion, Gombrich 1960, fifth Ed 1977, page 46

We were not endowed with this capacity by nature in order to produce art: it appears that we could never find our way about in this world if we were not thus attuned to relationships. Just as a tune remains the same whatever the key it is played in, so we respond to light intervals, to what have been called “gradients’, rather than to the measurable quantity of light reflected from any given object.

And when I say ‘we’, I include newly hatched chickens and other fellow-creatures who so obligingly answer the questions psychologists put to them.

According to a classic experiment by Wolfgang Kohler, you can take two grey pieces of paper— one dark, one bright—and teach the chickens to expect food on the brighter of the two. If you then remove the darker piece and replace it by one brighter than the other one, the deluded creatures will look for their dinner, not on the identical grey paper where they have always found it, but on the paper where they would expect it in terms of relationships—that is, on the brighter of the two. Their little brains are attuned to gradients rather than to individual stimuli. Things could not go well with them if nature had willed it otherwise. For would a memory of the exact stimulus have helped them to recognize the identical paper ? Hardly ever! A cloud passing over the sun would change its brightness, and so might even a tilt of the head, or an approach from a different angle.

If what we call ‘identity’ were not anchored in a constant relationship with environment, it would be lost in the chaos of swirling impressions that never repeat themselves.

However perhaps Gombrich took the words of Ruskin and Monet too literally. As he mentions later on, what they were advocating in practice was really a more dogmatic version of the approach which Marshall Smith* had explained in 1692, and which had formed the basic approach of representational painters for many centuries. 19th century authors may have talked about the ‘retinal image’ but in practice they were not attempting to duplicate that image, but the image-in-the-viewfinder. (Not forgetting that that image in turn can give rise to the retinal image). What Ruskin and Monet were advocating was a particularly rigorous comparison of nature with our expectations, and – most importantly – they sought to make this process obvious to the viewer by leaving the brushstrokes clear and unblended. Pretty much all artists had applied paint as the mosaic artists of Pompeii had applied tesserae. Vermeer made this process more apparent than many others, but not as unmissably as the Impressionists. What was distinctive about the Impressionist approach was that it threw so much emphasis on this early stage in the construction of a painting.

*The Art of Painting (1692)

Marshall Smith

https://archive.org/details/artofpaintingacc00smit

GOMBRICH – THE EYE IS ALWAYS BIASED – IT CANNOT WORK OTHERWISE

But though we can accept much of Berkeley’s account, we must doubt all the more whether such an achievement of innocent passivity is at all possible to the human mind.

Whenever we receive a visual impression, we react by docketing it, filing it, grouping it in one way or another, even if the impression is only that of an inkblot or a fingerprint.

Roger Fry and the impressionists talked of the difficulty of finding out what things looked like to an unbiased eye because of what they called the ‘conceptual habits’ necessary to life. But if these habits are necessary to life, the postulate of an unbiased eye demands the impossible.

It is the business of the living organism to organize, for where there is life there is not only hope, as the proverb says, but also fears, guesses, expectations which sort and model the incoming messages, testing and transforming and testing again. The innocent eye is a myth.

That blind man of Ruskin’s who suddenly gains sight does not see the world as a painting by Turner or Monet-even Berkeley knew that he could only experience a smarting chaos which he has to learn to sort out in an arduous apprenticeship. Indeed, some of these unfortunates give up and never learn it at all.

Gombrich Art and Illusion, page 251

For seeing is never just registering. It is the reaction of the whole organism to the patterns of light that stimulate the back of our eyes; in fact, the retina itself has recently been described by J. J. Gibson as an organ that does not react to individual stimuli of light, such as were postulated by Berkeley, but to their relationship, or gradients.

We have seen that even newly hatched chickens classify their impressions according to relationships. The whole distinction between sensation and perception, plausible as it was, had to be given up in the face of the evidence from experiments with human beings and animals. Nobody has ever seen a visual sensation, not even the impressionists, however ingenuously they stalked their prey.

We seem to have arrived at an impasse. On the one hand, Roger Fry’s and Ruskin’s accounts of painting do somehow correspond with the facts. Representation really does seem to advance through the suppression of conceptual knowledge.

On the other, no such suppression appears to be possible.

It is an impasse which has led to a certain amount of confusion in writing on art. The easiest way out is to deny the traditional reading of the historical facts altogether.

If there is no unbiased eye, Roger Fry’s account of the discovery of what things look like to such an unbiased eye must be false.

The reaction against impressionism which we witnessed in the twentieth century increased the appeal of such a conclusion. Here was another convenient stick with which to beat the Philistine who wanted paintings to look like nature. The demand was nonsense.

If all seeing is interpreting, all modes of interpretation could be argued to be equally valid.

Perhaps this conundrum can be resolved. We could stop thinking of the probing eye as being altogether different from the innocent eye, and instead think of both modes of observation as being at opposite ends of the same scale – a scale of visual vocabulary. One end is rich and full, the other simple and basic.

THE EYE AND BRAIN SEARCH RATHER THAN RECEIVE

ACTIVE AND PASSIVE THEORIES OF PERCEPTION

Chapter XV Of the Face.

Hogarth meant these heads to illustrate a scale from a head of the ‘highest taste’ (97) to the lowest (104).

97 illustrated lines of beauty flowing throughout the form, and 104 illustrated their complete absence.

Whether or not Hogarth’s theory of the line of beauty proves correct, his inquisitive way of examining what he saw is a perfect example of Gombrich’s ‘searchlight’ account of perception.

DRAWING WITHOUT PRE-CONCEPTIONS

The bucket theory assumes that all the light which comes into the eye forms an image on the retina. The artist would be able to see things, “as they really were”, as long as he or she subdued his or her preconceptions (for example by not drawing a line around a head).

However the eye and brain cannot work like this.

As in the descriptions above, a motorist may fail to see a cyclist because, just like a shopper looking for a packet of coffee in a supermarket, his or her eye and brain are primed to look for a car – not a cyclist.

When painting what appears in the viewfinder, the artist is on the lookout for areas of colour and tone which can be matched with patches of paint. This is not looking without preconceptions, as it is often described. It is looking with a specific purpose in mind – the finding of coloured shapes.