COLDSTREAMS’S ATTEMPT TO AVOID IMPOSING HIS OWN WILL POWER.

Winifred Burger 1937

http://www.tate.org.uk/art/work/T00339

Casualty Reception Station, Capua 1944

http://www.tate.org.uk/art/work/T01107

Coldstream believed in correcting his painting by referring to measurements of what would appear in a viewfinder. He would have preferred not to have to correct in this way, but felt impelled to keep such a check on himself. (The method was described earlier on). This process would lead to a sort of innocence – it would prevent him from imposing his own will power (formulae, or preconceptions).

The method was known as the ‘Euston Road’ approach, named after the road where he and some friends had set up an art school (1937-39), and where this approach gained prominence.

COLDSTREAM: AN UNPUBLISHED INTERVIEW, 1962

David Sylvester: And when representing you always measure?

The paintings of William Coldstream, 1908-1987,

William Coldstream: Well I try very hard not to. But I’m always driven back to it because it seems to me to be extremely interesting to what I call ascertain something. I know, of course, this is childish because the measurement in a sense is conventional. But the idea of making sure about the thing, within the limits of the game, it means a lot to me.

William Coldstream: … If you’re trying to get something going by your own will power, without reference to something that seems impersonal, it gives me a sense of distaste. I’m afraid this is very obscure. But if you have this rather sort of arbitrary thing, you feel the problem that’s coming out is not one which you’ve been too much consciously associated with and therefore has that attraction. But I think this is all a very grand way of describing what hundreds of painters have often done.

Lawrence Gowing and David Sylvester

Tate Gallery, 1990

We saw earlier that artists very different temperaments, Rodin and Giacometti, had both believed that their work was true to nature, true to something outside themselves. They were not simply repeating learned schemata or formulae, nor making literal copies of what would appear in a viewfinder.

Coldstream expressed a similar desire to restrain his output by checking against something outside himself, but Coldstream relied on accurate measurement rather than on the feeling for true nature which Rodin and Giacometti had adopted as a check.

For thousands of years, the traditional means of applying this kind of check had been to correct complex schemata – such as whole figures. Such corrections were far less restrictive than Coldstream’s. Sickert described how he had seen Degas make just such a correction .

Cafe in Dieppe 1885

An example of the type of painting that Sickert was producing about the time he posed for the Degas pastel below.

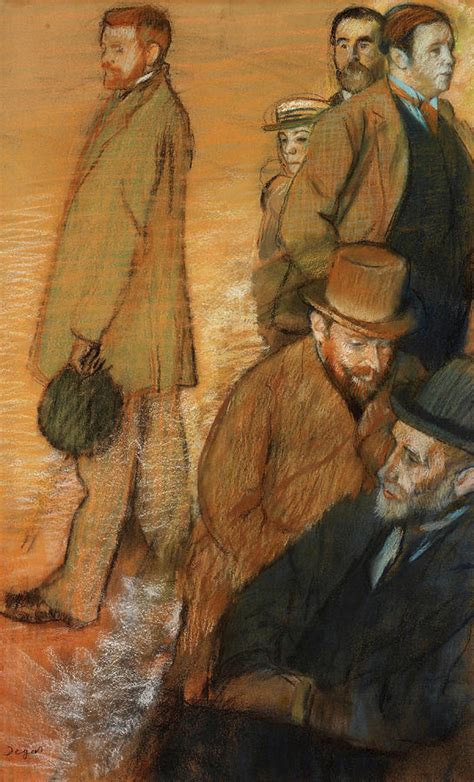

Six Friends at Dieppe, 1885.

Pastel on paper.

(Sickert appears at left, standing)

It was in France in 1885 that I received a lesson in criticism that I have not forgotten. Monsieur Degas, then in the fifties, and at the height of an uncontested and world-wide reputation, was at work on a portrait group for which I was one of the models. Gervex, then a young man under thirty, was another. During a rest, I was somewhat surprised to see Degas, by a gesture, invite Gervex to look at the pastel on which he was working, and Gervex, in the most natural manner in the world, advance to the sacred easel, and, after a moment or two of plumbing and consideration, point out a suggestion. The greatest living draughtsman resumed his position at the easel, plumbed for himself, and, in the most natural manner in the world, accepted the correction. I understood on that day, once for all, the proper relation between youth and age. I understood that in art, as in science, youth and age are equal. I understood that they both stand equally corrected before a fact. . . .

W. R. Sickert

‘The Burlington Magazine‘, April 1916

Quoted in ‘A Free House!‘ p196

But where the old masters had thought in whole figures, Coldstream thought in little lines.

Coldstream’s approach was very important for a certain period in the history of British painting. In the 1950’s the fashion had gone over to either ‘School of Paris’ (which meant Picasso, Braque and associates) or Abstract Expressionism (which meant Jackson Pollock, de Kooning and associates). Comparatively realistic representational painting had its back against the wall. Many commentators felt that the “Euston Road” approach might save representational painting from being ignored by contemporary writers.

Girl with a mandolin (Fanny Tellier) 1910

Museum of Modern Art New York.

Bottle and Fishes c.1910-12

http://www.tate.org.uk/art/work/T00445

Yellow Islands 1952

http://www.tate.org.uk/art/work/T00436

Women Singing II 1966

http://www.tate.org.uk/art/work/T01178

I remember, in about 1970, the principal of the Byam Shaw School declared to a fellow student: “The Euston Road approach is the only valid way in which to make representational paintings these days.” (What exactly he meant by ‘valid’ remains a mystery). Anyone who wished to paint like the Old Masters was considered to be an absurd irrelevance as far as serious painting was concerned.

The Euston Road approach was very attractive intellectually. It offered a simple way in which to avoid schemata or formulae – to achieve a perfectly innocent eye. The painter could be safe from the accusation of imitating the old masters. No further thought was required. There was no need for that intense industry that Reynolds had considered essential, “… not the industry of the hands, but of the mind.” (Discourse 7).

One might expect that such a rigid procedure would produce sterile results. However, as his pictures show, Coldstream did have a feeling for grandeur. This makes itself felt in all his work. His admirers often regretted that his self-doubt had restricted a flair for beautifully placing areas of tone and colour.

Coldstream’s talent does not seem to have been perfectly in tune with his theory. Every artist has to work towards such a personal theory, each in his or her own way. This thoughtful process is part of that ‘solid science’ which Reynolds wrote about. It is not something that comes automatically.