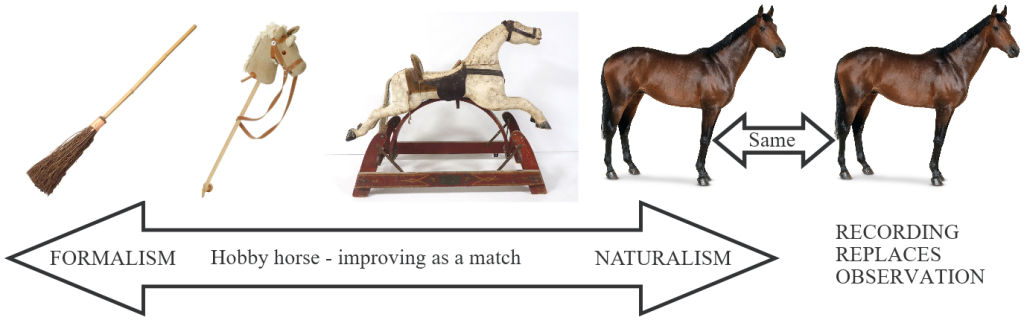

THE HOBBY HORSE – ILLUSION TO DELUSION

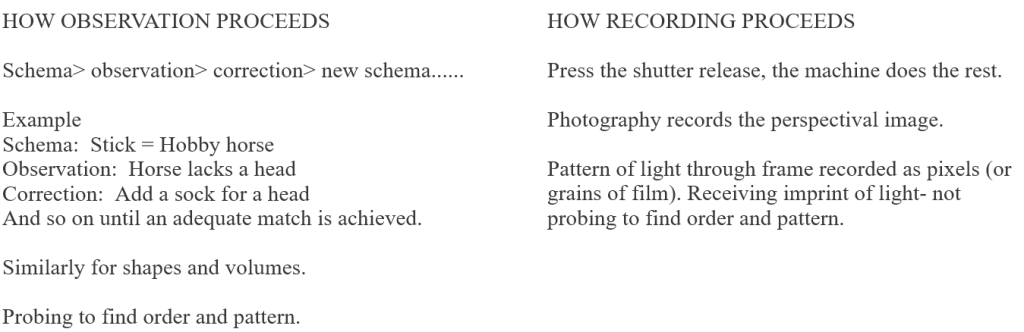

The child observes the differences between a real horse and the hobby horse, and reduces these by adding modifications. The defects of the imitation are informative: they tell the viewer what the child has noticed. The child may add a sock to a broom to indicate a head, then add beads to indicate eyes. An adult may assist the process and even come up with a rocking horse, and so on.

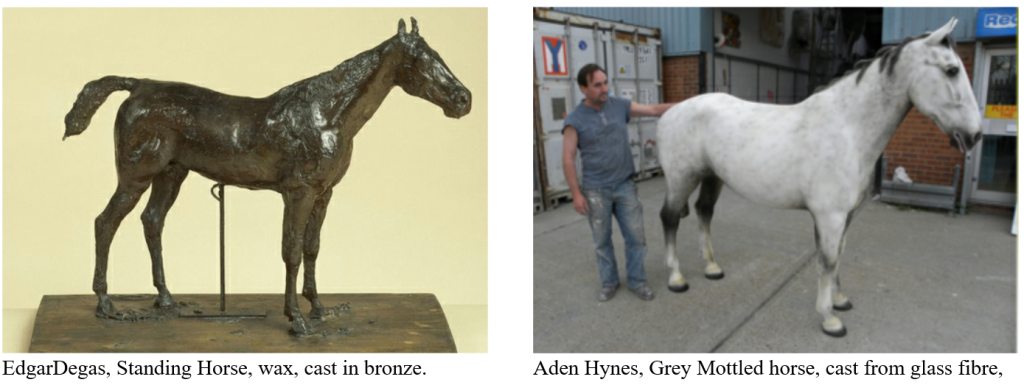

But when a skilful worker duplicates a horse by 3D digital means, the result contains no information about any observations that may have been made. The perfect duplicate is not informative: the viewer cannot identify what the workman or the machine has noticed.

On the right , in contrast, is an example of a 3D cast. It is a phenomenal achievement, but does not point out anything to the viewer.

*Degas, sa vie et son oeuvre by P. A. Lemoisne 1946

INFORMATION – THE VALUE OF ILLUSION VERSUS DELUSION

The art historian, E H Gombrich, described how a child might use a broomstick as a make-believe horse, a hobby-horse, even though it bears very little resemblance to a real horse. The child may go on to supply deficiencies one by one, for example by adding a sock for a head, beads for eyes, and so on. If this process were continued the resemblance would become so nearly complete that a viewer might be deluded into believing that the representation was a real horse. The illusion would have become a delusion.

But the child is not deluded. The child knows that his hobby-horse is not a horse, even though he treats it as if it were. Each modification which the child makes to the broomstick tells the viewer something that the child has noticed. As a facsimile, the result is imperfect, but the imperfections are informative.

A perfect duplicate is not informative in this way. When a life-cast is made of a horse, or the horse is duplicated by digital means, the result does not tell the viewer anything about what the maker has observed. The work provides no information about anyone’s observations. As a peasant, looking at a realistic painting of a tree, said to the famous French painter Millet (1814 – 1875), “why not simply look at a tree?”

Potato Planters, 1861

Sometimes it is said that the child is merely replicating a verbal understanding, using lines only as replacements for words. For example, instead of saying ‘face’ the child may draw a rough circle. Arguably the child is not thinking about the shape of a real face. But this is too crude an account of what the child is doing. As the child makes further observations he or she will add to the drawing. The drawing, no matter how rudimentary, is a visual equivalent for a visual experience. This relationship between vision and drawing may be developed as the child extends his or her visual vocabulary, so that the drawing becomes increasingly accurate as a replica of what the child has seen – ever more like a photograph.

WE ARE NOT ALWAYS PLEASED WITH THE MOST ABSOLUTE POSSIBLE RESEMBLANCE

SIR JOSHUA REYNOLDS ON WAXWORKS

I do not mean to prescribe what degree of attention ought to be paid to the minute parts; this it is hard to settle. We are sure that it is expressing the general effect of the whole, which alone can give to objects their true and touching character; and wherever this is observed, whatever else may be neglected, we acknowledge the hand of a master. We may even go further, and observe that when the general effect only is presented to us by a skilful hand, it appears to express the object represented in a more lively manner than the minutest resemblance would do.

These observations may lead to very deep questions, which I do not mean here to discuss. Among others, it may lead to an inquiry why we are not always pleased with the most absolute possible resemblance of an imitation to its original object. Cases may exist in which such a resemblance may be even disagreeable. I shall only observe that the effect of figures in waxwork, though certainly a more exact representation than can be given by painting or sculpture, is a sufficient proof that the pleasure we receive from imitation is not increased merely in proportion as it approaches to minute and detailed reality; we are pleased, on the contrary, by seeing ends accomplished by seemingly inadequate means.

Joshua Reynolds, DISCOURSE XI.

Delivered to the Students of the Royal Academy, on the Distribution of the Prizes, December 10, 1782.

A photograph typically records the pattern of light (or ‘array’ of light) which entered the camera during a fraction of a second. In contrast, a child’s drawing typically records observations that were made over a period of time, during which both the child and the subject were moving. For example, if a child draws the portrait of someone in the same room, he or she may start with a primordial circle in order to represent the head, then look again and see hair attached to the head, and scribble in a few lines to represent this. The subject may have moved to a different part of the room, yet the observation is added to the same drawing. Thus time and movement contribute to a child’s drawing far more than they do to a photograph, or a photographic painting.

This sort of thing may be seen in classical drawing, say the drawing of Raphael. Lines are drawn to represent egg-like volumes, which themselves represent parts of the body. These are shown with a clarity which is far more powerful than if the lines had been drawn as the sort of tracing which the artist in Dürer’s illustration was making. The kind of translation which Raphael made may be seen in his copy of the Mona Lisa. Thousands of art students could make tracings more accurate than Raphael’s, but his copy demonstrates an extremely lucid translation into egg-like volumes.

Observations of grouping, e.g. Drapery, how folds move around a limb, means movement of the subject or artist – or both.

Volume is more clearly appreciated over time than in an instant.

The drawing records an analysis of something seen as it changed over time.

If a moment in time is frozen, as in a snapshot, some objects become invisible which would be seen easily in real life – “the movie that is nature” as the painter WR Sickert (1860 – 1942) called it. The French writer, journalist and humourist, Alphonse Allais (1854 – 1905) showed this graphically in some amusing images.

First Communion of Anaemic Young Girls In The Snow (1883)

Apoplectic Cardinals Harvesting Tomatoes on the Shore of the Red Sea (Study of the Aurora Borealis)

If one were in a position to see these scenes in real life (supposing they might ever exist), the slightest movement on any of the people or objects would catch the light and the observer would see where they were. An observer’s memory of the real scene would be quite different from the frozen images.

There was another artist who exploited this phenomenon to eye-catching effect: Coles Phillips (1880-1927). His pictures of “fade-away girls” playfully exploited the loss of outline which occurs when the colour of an object perfectly matches that of the background. The viewer cannot locate the edge of an object because there are no visual cues, such as might be provided by the light catching an edge during movement. Coles was able to contrast differential analysis with its complete absence.

Cover art for Life Magazine, dated January 27, 1910

THE PROGRESS TOWARDS THE PHOTOGRAPH – HISTORICAL VIEW

Considering the development of art from Giotto (1267– 1337) to Monet (1840 – 1926), it may seem as if artists have been attempting to get ever nearer to producing a photograph. Over this time period their pictures became increasingly true to nature (if nature may be said to be what appears in the viewfinder). This movement proceeded, as Gombrich described, less from a desire to achieve photographic accuracy, than from a desire to remove features of a depiction which looked false. If differences between a picture and the scene in the viewfinder were removed, step-by-step, the final result would be a perfect replica of what appears in the viewfinder.

For practical purposes, this final step was taken when the photograph was invented. An entirely objective record could then be made of the image on the picture plane. The photograph included none of the falsities which artists had been learning to remove from their hand-made pictures. However even the photograph, which seemed to have answered all previous demands for an image which was true-to-life, did not satisfy. There was something amiss, hence the move towards ‘Naturalistic Photography’ which was discussed above. Despite its staggering accuracy, the photograph did not seem to be fully ‘true to nature’.

But the word, “Nature” can mean different things to different people, and so can give rise to many misunderstandings. This comes out very clearly in the following interview with the famous sculptor, Auguste Rodin (1840 – 1917). Rodin starts by saying he only wished to be servilely faithful to nature, but ends by saying that the artist is one who, “reads deeply into the bosom of Nature.” A life-cast or a waxwork, accurate in every detail, would not satisfy Rodin as having been true to Nature – in his particular use of the word. Distortion of the reality of a cast was an essential requirement. Or, as Emerson might have termed it, Differential Analysis must be displayed otherwise a sculpture would be only a copy.

RODIN – THE HIDDEN TRUTHS BENEATH APPEARANCES

“Prodigal Son,” first modeled about 1886, cast about 1928 or earlier

This shows that Rodin’s idea of being true to nature was very different from providing an accurate transcription such as a life-cast.

From Rodin, On Art and Artists, Alfred Werner 1957:

In this passage, Werner recalls a conversation he had with Rodin. Rodin speaks first.

“I obey Nature in everything, and I never pretend to command her. My only ambition is to be servilely faithful to her.”

“Nevertheless,” I answered with some malice, “it is not nature exactly as it is that you evoke in your work.”

He stopped short, the damp cloth in his hands. “Yes, exactly as it is!” he replied, frowning.

“You are obliged to alter —”

“Not a jot!”

“But, after all, the proof that you do change it is this, that the cast would give not at all the same impression as your work.”

He reflected an instant and said: “That is so! Because the cast is less true than my sculpture!

“It would be impossible for any model to keep an animated pose during all the time that it would take to make a cast from it. But I keep in my mind the ensemble of the pose and I insist that the model shall conform to my memory of it. More than that,—the cast only reproduces the exterior; I reproduce, besides that, the spirit which is certainly also a part of nature.

“I see all the truth, and not only that of the outside.

“I accentuate the lines which best express the spiritual state that I interpret.”

As he spoke he showed me on a pedestal near by one of his most beautiful statues, a young man kneeling, raising suppliant arms to heaven. All his being is drawn out with anguish. His body is thrown backwards. The breast heaves, the throat is tense with despair, and the hands are thrown out towards some mysterious being to which they long to cling.

“Look!” he said to me; “I have accented the swelling of the muscles which express distress. Here, here, there — I have exaggerated the straining of the tendons which indicate the outburst of prayer.”

And, with a gesture, he underlined the most vigorous parts of his work.

“I have you, Master!” I cried ironically; “you say yourself that you have accented, accentuated, exaggerated. You see, then, that you have changed nature.”

He began to laugh at my obstinacy.

“No,” he replied. “I have not changed it. Or, rather, if I have done it, it was without suspecting it at the time. The feeling which influenced my vision showed me Nature as I have copied her.

“If I had wished to modify what I saw and to make it more beautiful, I should have produced nothing good.”

An instant later he continued:

“I grant you that the artist does not see Nature as she appears to the vulgar, because his emotion reveals to him the hidden truths beneath appearances.

“But, after all, the only principle in Art is to copy what you see. Dealers in aesthetics to the contrary, every other method is fatal. There is no recipe for improving nature.

“The only thing is to see.

“Oh, doubtless a mediocre man copying nature will never produce a work of art; because he really looks without seeing, and though he may have noted each detail minutely, the result will be flat and without character. But the profession of artist is not meant for the mediocre, and to them the best counsels will never succeed in giving talent.

“The artist, on the contrary, sees; that is to say, that his eye, grafted on his heart, reads deeply into the bosom of Nature.

“That is why the artist has only to trust to his eyes.”

RODIN’S IDEA OF TRUTH TO NATURE

The following photographs give a rare opportunity to compare a famous sculpture with the model, or at least with one of the models who posed for it. Clearly, for Rodin, being true to nature did not mean being accurate.

Right: Rodin: St John the Baptist Preaching 1877

To take revenge on those who had accused him of moulding from the body, Rodin made his St John the Baptist Preaching (1877, p. 23) larger than life. It was composed, like Frankenstein*, from a variety of different elements: the Walking Man for the body, his friend Danielli for the face, and an Italian for the pose.

Judith Cladel, a loyal mistress of Rodin’s, describes the model photographed here in the pose of the St John the Baptist:

“A robust peasant from Abruzzi, called Pignatelli… He undressed, got onto the model’s table, planted himself firmly on his feet, and, head up, stretching one arm forward with a proud gesture as he spoke, he stepped forward. With his shaggy growth of hair and sparkling eyes, he was a kind of savage: ‘He’s like a wolf,’ said Rodin.”

The St John originally carried a cross on his shoulder, but this broke the sweep of the composition and Rodin left it out.

Gilles Néret 1994

* Néret must mean Frankenstein’s creature, not the scientist himself.

Auguste Rodin

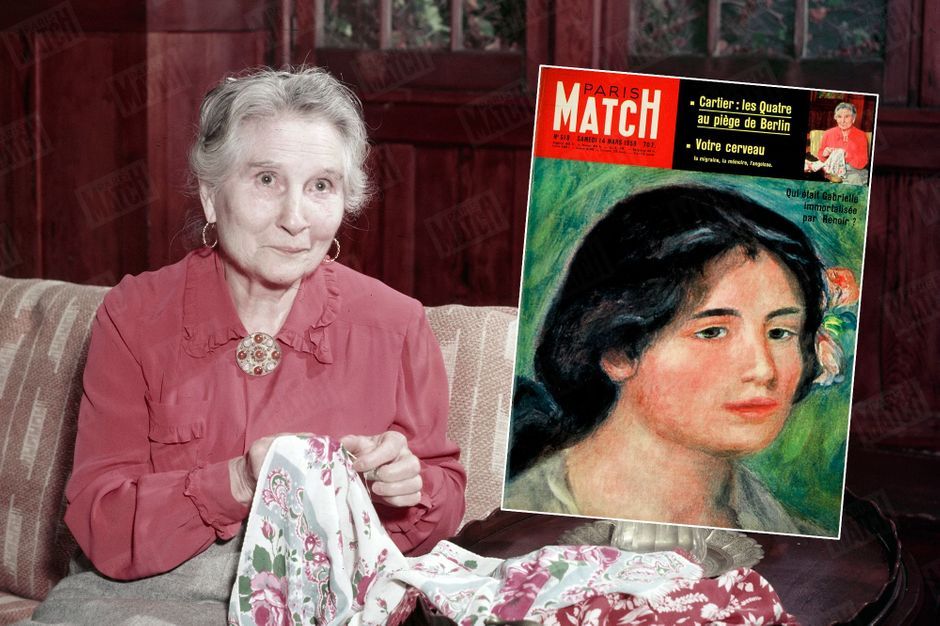

The inset shows the nurse as painted by her employer, Auguste Renoir.

On the cover of Paris Match n°518, dated March 14, 1959.

https://resize-parismatch.lanmedia.fr/r/940,628/img/var/news/storage/images/paris-match/culture/art/renoir-modele-gabrielle-renard-nourrice-1610958/26072524-1-fre-FR/Qui-etait-Gabrielle-immortalisee-par-Renoir.jpg

Even though the model is clearly younger in the painting than in the photograph, the comparison does give some idea of the sort of distortions that Renoir felt were essential.

In contrast with Rodin, Renoir (1841 – 1919) was very direct when speaking about the necessity of distortion:

It is precisely because one knows how to draw that one is obliged to distort.

From ‘The Bulletin de la Vie Artistique’ quoted in

Renoir, his Life and Work (1961)

François Fosca (1881 – 1980)

TRUTH TO CHARACTER

This is one of the reasons that the illustrator, Andrew Loomis (1892 – 1959), insisted that students, when drawing from photographs, should always do so freehand; so that their understanding and fluency would not be interrupted by restrictive measurement, or tracing.

In the quotation above, Rodin made it clear that a plaster cast of the model, even if scaled up or scaled down, would not satisfy his demands. For him, truth to nature did not mean literal accuracy. Such accuracy would be only, ‘flat and without character’.

In painting and sculpture, the word, ‘character’ has a physical meaning. For example a ball is fat in character, while a drain-pipe is thin in character. Thus every form has a physical character. It is arguably the artist’s task to bring out this character – to exaggerate it. In other words, if a sculpture is to be true in character, it must be a distortion of real life. This introduces an element of subjectivity. Confronted with a rugby ball, say, one artist might interpret it as being fat, another might interpret it as being thin.

Ideally, as they were creating a work, artists themselves would be so completely convinced by their own interpretation that, to them, their distortions would not feel like falsifications, but like revelations of an objective truth – as if they were reading, “deeply into the bosom of Nature.”

Rodin distinguished between distortion which derived from such deep feeling and understanding, and one which was wilful and imposed.

Viewers may look at the work and reflect on their own responses.

Is the sculpture made of volumes of such character that they give a heightened sense of life and movement?

Or are they remarkable only for being accurate – life-like in the prosaic sense?

Does it look as if the forms have been distorted in a way which is convincing?

Or does it look as if the artist has been applying distortions in a way that does not add up to a coherent interpretation?

It may be impossible to come to a conclusion at first sight. A sculpture may require repeated visits before viewers can begin to find a consistency in their own responses. This is partly because, if viewers wants to appreciate a work as fully as possible, part of their task is to bring their own knowledge and experience. Appreciating a work of art is not simply a matter of lying back and asking, ‘does this do anything for me?’ It is a matter of looking and asking questions. For example:

What is the character of the forms presented here?

Fat, thin, curvaceous, straight?

What if these forms had been less exaggerated, or more exaggerated?

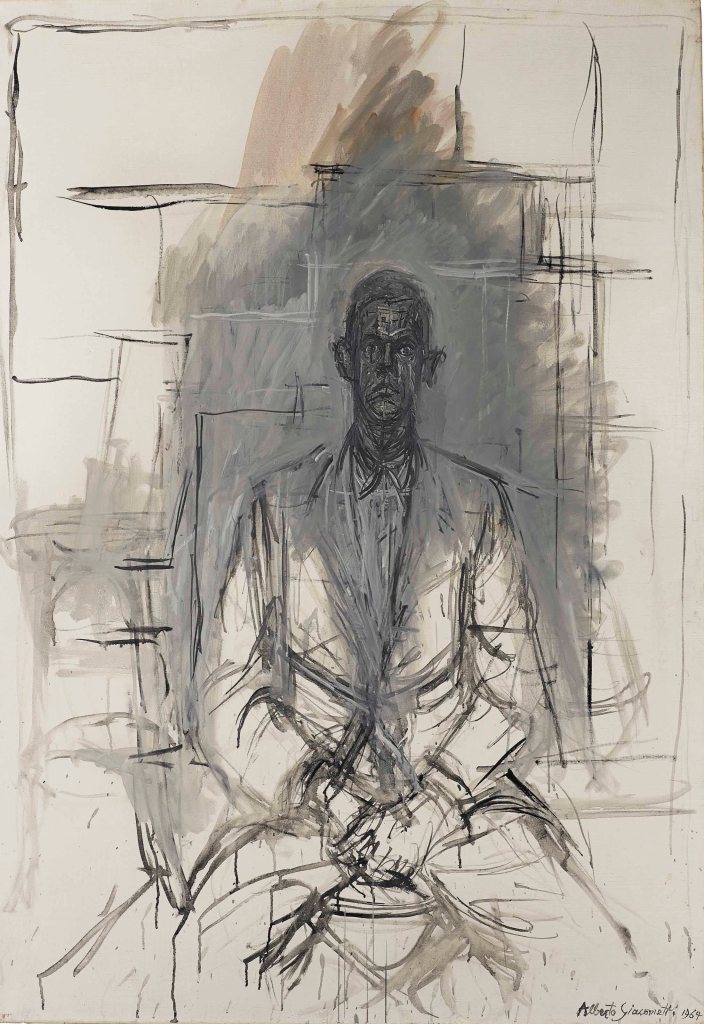

GIACOMETTI – TRUE TO HIS IDEA OF NATURE

Head of Diego as a Child – 1914-15.

This shows that Giacometti, at age 13 or 14, was capable of very naturalistic sculpture.

Head of a girl with braid – Ida

An early work of unknown date, but before he began to be influenced by Cubism and Surrealism.

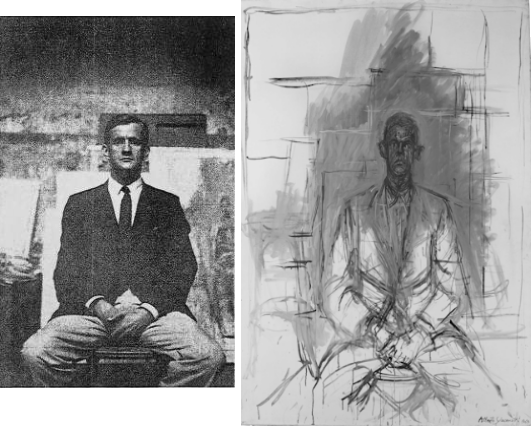

Giacometti (1901 – 1966) provides another example of an artist who insisted that he was attempting to match what he saw as accurately as possible, yet whose results were completely unlike the image in the viewfinder or a life-cast. While working on his portrait of James Lord, Giacometti continually complained that he could not get the simplest things right, like making the nose perpendicular to the body.

It seems as though, like Rodin, Giacometti was constructing an object which somehow corresponded with relationships which he observed, considered important, and worth extracting: he was looking for a match in emphasis, rather than a match in dimension.

And a little later he said. “If someone else tried to do what I’m doing, he’d have the same difficulties I’m having.”

James Lord, A Giacometti Portrait, New York, 1965.

“But,” I asked, “is anyone else trying to do what you’re trying to do?”

“I can’t think of anyone. And yet it seems simple. What I’m trying to do is just to reproduce on canvas or in clay what I see.”

“Sure. But the point is that you see things in a different way from others, because you see them exactly as they appear to you and not at all as others have already seen them.”

“It’s true that people see things very much in terms of what others have seen.” he said. “It’s simply a question of the originality of a person’s vision, which is to see, for example, and really to see, a landscape instead of seeing a Pissarro. That’s not as easy as it sounds, either.”

James Lord

signed and dated ‘Alberto Giacometti 1964’ (lower right)

oil on canvas

45 ¾ x 31 ¾ in. (115.9 x 80.6 cm.)

Painted in 1964

REMINDING VERSUS DECEIVING

Gombrich wrote, in the preface to the 2000 edition of Art and Illusion:

“There is a passage in John Constable’s correspondence which seems to me immensely telling in this respect. Constable was one of my principal witnesses in ‘Art and Illusion’ because of his ability and his dogged determination to get rid of all second-hand conventions—or what he called “manner”—and to achieve a maximum fidelity to natural appearances. In 1823 Constable visited a sensational display, the diorama constructed by Daguerre, later the inventor of the daguerrotype.

It is in part a transparency,” he wrote, “the spectator is in a dark chamber, and it is very pleasing and has great illusion. It is outside the pale of art because its object is deception. The art pleases by reminding, not deceiving.”

John Constable (1776 – 1837), quoted in:

John Mayne (ed.), C. R. Leslie, Memoirs of the Life of John Constable, Phaidon (London), 1951, p. 106.

(When he wrote, “The art”, Constable was referring to the art of painting).

Gombrich continues:

“Outside the pale of art”—what could he have meant by that pale, or limit?

E. H. Gombrich, Art and Illusion

Would we go quite wrong in suggesting that, for Constable, art had become something like a game of skill, with its own rules, which must be kept free of labour-saving devices? To deceive the eye is to cheat, for the painter must please by reminding, just as the playwright of Shakespeare’s Prologue [1] must work on our “imaginary forces.” Fidelity to nature has to be achieved within the limits of the medium. Once this compact between the artist and the beholder is destroyed, we are outside the pale of art. Indeed, as soon as Daguerre’s and Fox Talbot’s mechanical methods entered the field, art had to shift the goalposts, and move the pale elsewhere.”

[1] the Prologue to Henry V.

Here Gombrich suggests that photography forced art to shift the goalposts, but, as we have seen with Reynolds and here, with Constable, the most significant artists fully understood that the goal of ‘the art’ was not to achieve a kind of photograph. They had explained this well before photography had been invented. For them, the goalposts did not need to be shifted. Delusion had never been the goal.

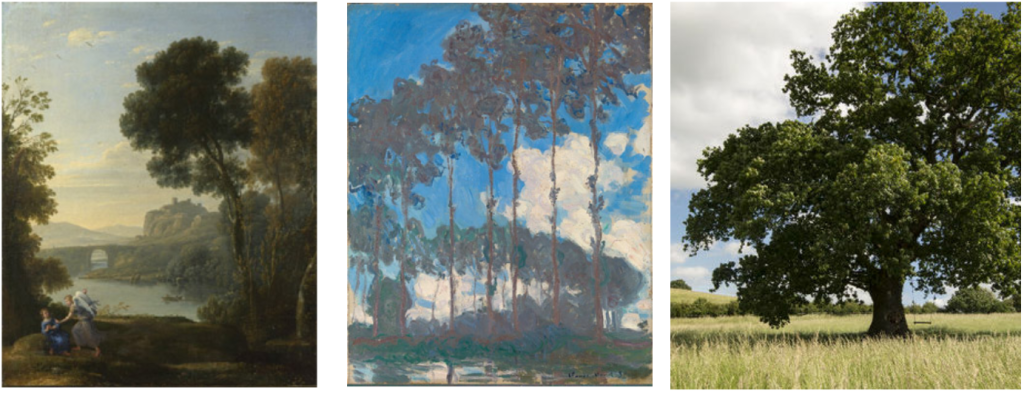

KNOWLEDGEABLE EYE PAINTING

via Monet (innocent eye painting)

to a photograph (technological recording)

Hagar and the Angel

Here Turner has brought to the task a mind filled with a massive range of memorised shapes: trees, mountains, figures, and hundreds of other features – all fill one of the best-stoked memories in the history of art. Tuner has combined these memorised shapes, varying and arranging them partly to suit his imagination and partly to match a genuine location. There is a playful element in the activity of joining and reshaping. This, together with observation, memory, and imagination produce a final work which is many-layered in meaning.

INNOCENT EYE PAINTING

Here Monet has eliminated from his mind all those memorised shapes which Turner called upon when constructing his painting.

Monet has restricted himself to a single type of expectation; not looking out for trees, mountains and figures, but only for patches of colour – nothing else.

Schema> observation> correction> new schema……

Example:

Schema: A patch of brown paint. Observation: Shape (of foliage) has shapes sticking out (trunk)

Correction: Adjust shape of patch of paint.

And so on until an adequate match is achieved.

NOTE: This is not painting without preconceptions, as is so often claimed.. It is painting with a specific type of preconception – one which is purposely extremely limited..

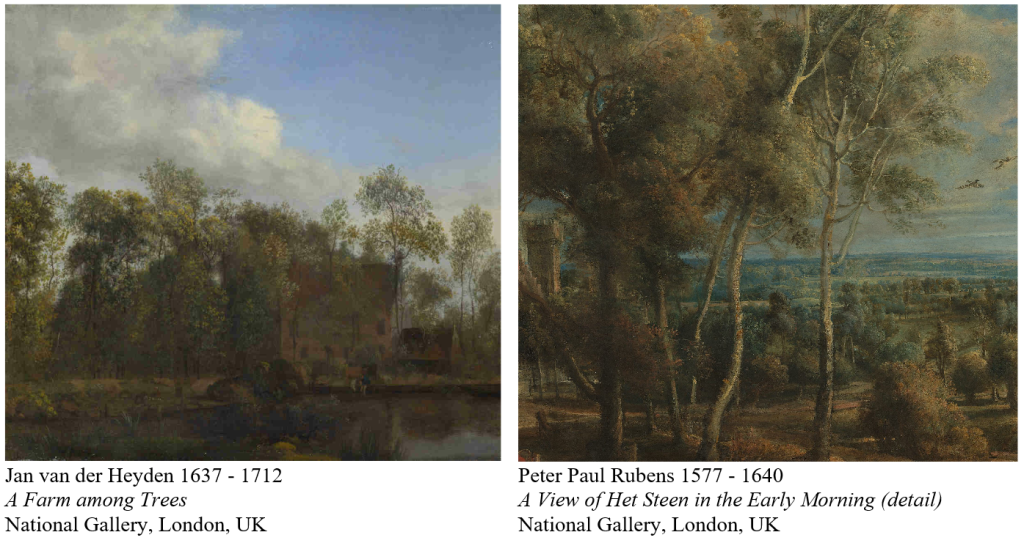

SIR JOSHUA REYNOLDS ON COPYING THE IMAGE IN THE CAMERA

If our judgments are to be directed by narrow, vulgar, untaught, or rather ill-taught reason, we must prefer a portrait by Denner, or any other high finisher, to those of Titian or Van Dyck; and a landscape of Van der Heyden to those of Titian or Rubens ; for they are certainly more exact representations of nature.

Sir Joshua Reynolds (1723 – 1792)

DISCOURSE 13. Delivered to the Students of the Royal Academy, on the Distribution of the Prizes, December 11, 1786.

Charles Burney, 1781

An example of the way in which Reynolds could generalise and simplify at the same time as producing a strong illusion of reality.

If we suppose a view of nature represented with all the truth of the camera obscura, and the same scene represented by a great artist, how little and mean will the one appear in comparison with the other, — where no superiority is supposed from the choice of the subject ! The scene shall be the same, the difference only will be in the manner in which it is presented to the eye. With what additional superiority, then, will the same artist appear when he has the power of selecting his materials as well as elevating his style. Like Nicholas Poussin, he transports us to the environs of ancient Rome, with all the objects which a literary education makes so precious and interesting to man; or, like Sebastian Bourdon, he leads us to the dark antiquity of the pyramids of Egypt; or, like Claude Lorrain, he conducts us to the tranquillity of Arcadian scenes and fairyland.

Like the history painter, a painter of landscapes, in this style and with this conduct, sends the imagination back into antiquity; and like the poet, he makes the elements sympathize with his subject, — whether the clouds roll in volumes like those of Titian or Salvator Rosa, or, like those of Claude, are gilded with the setting sun; whether the mountains have sudden and bold projections, or are gently sloped ; whether the branches of his trees shoot out abruptly in right angles from their trunks, or follow each other with only a gentle inclination. All these circumstances contribute to the general character of the work, whether it be of the elegant or of the more sublime kind. If we add to this the powerful mate rials of lightness and darkness, over which the artist has complete dominion, to vary and dispose them as he pleases, to diminish or increase them as will best suit his purpose and correspond to the general idea of his work, — a landscape thus conducted, under the influence of a poetical mind, will have the same superiority over the more ordinary and common views as Milton’s Allegro and Penseroso have over a cold, prosaic narration or description; and such a picture would make a more forcible impression on the mind than the real scenes, were they presented before us.

If we look abroad to other arts we may observe the same distinction, the same division into two classes – each of them acting under the influence of two different principles, in which the one follows nature, the other varies it, and sometimes departs from it.

The theatre, which is said to hold the mirror up to nature, comprehends both those ideas. The lower kind of comedy, or farce, like the inferior style of painting, the more naturally it is represented, the better; but the higher appears to me to aim no more at , so far as it belongs to anything like deception, or to expect that the spectators should think that the events there represented are really passing before them, than Raphael in his Cartoons or Poussin in his Sacraments expected it to be believed, even for a moment, that what they exhibited were real figures.

Sir Joshua Reynolds (1723 – 1792)

Excerpt from DISCOURSE 13.

Delivered to the Students of the Royal Academy, on the Distribution of the Prizes, December 11, 1786.

Art not merely imitation, but under the direction of the imagination. — in what manner poetry, painting, acting, gardening, and architecture depart from nature.

Here, Denner and the other ‘high-finisher’ painters were criticised by Reynolds. Reynolds warned that simply making an image which matched what appeared in the camera obscura would not be adequate. It would not show ‘imagination”. This concept of ‘imagination’ overlaps with what Emerson called “Differential Analysis”.

It may be worth clarifying the terms imagination, and memory.

If you can draw a shape which matches one you have seen that is an example of Memory.

If you construct an image of something you have not seen, for example a centaur, you may do this by combining and adapting images of horses and men that you have stored in your memory . In that way you would be demonstrating Imagination, and even Invention.

Reynolds is here using the terms rather as we have been doing so far, to indicate that the painter has constructed an image which is equivalent to the scene, but independent of it. This is similar to simplifying the scene, for example by drawing a complicated tree as one shape. But is it worth noting the difference between this sort of simplification and that which results from applying a filter in Photoshop. The computer simplifies in an unimaginative way. It works according to strict rules which do not distinguish between objects, only between colours and tones.

The following examples by Sir Alfred Munnings (1878 – 1959) show the process. The poster perhaps show it most clearly, but so does the simplification of the horse in the painting.

Munnings here combines observation, but, with a moving subject like this, he calls on his memories of horses studied before and invents a combination which matches his experiences of seeing the animal posing. This kind of painting cannot be done simply by copying a photograph with loose brushstrokes, (even if the painter uses a photograph as an aid). Only a mind well-prepared with study from memory and imagination is capable of producing an image with this degree of refinement. A computer- processed photograph cannot show this sort of simplification.

Portrait of Mr. Bayard Tuckerman 1924

Hethersett 1907

There is no mechanical way in which lines can be drawn around objects (differential analysis).