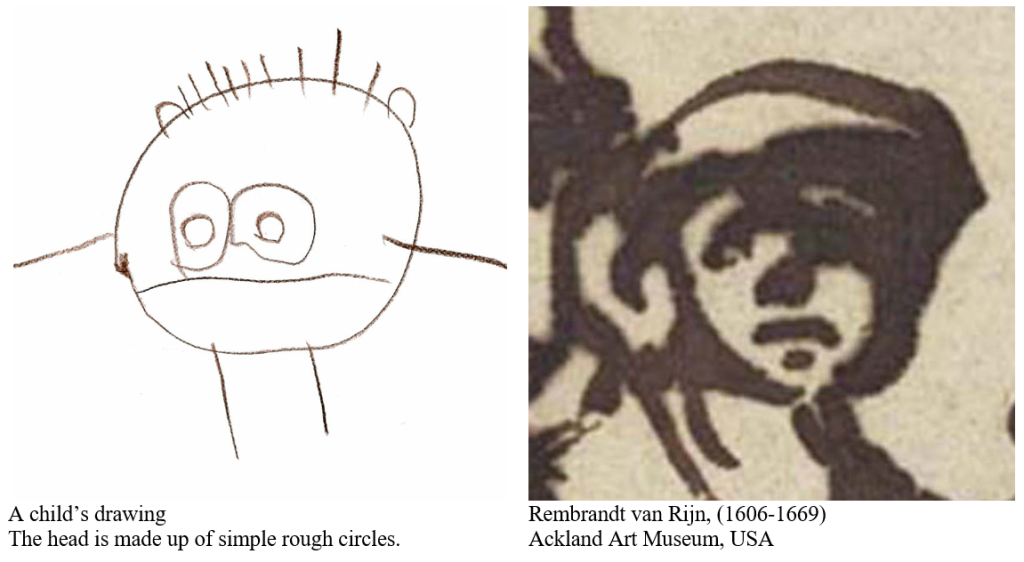

SCHEMATA OF INCREASING COMPLEXITY

Schema (plural – schemata): A plan, outline, or model.

Graphic Art in Easy Stages (1940)

Illustrating a method of building up complicated drawings from simple shapes.

How to Draw Birds 1940

Elaborating from comparatively simple shapes to a complicated design.

As far as drawing and painting are concerned, a schema may be as simple as a line, or a rough circle. More advanced schemata may be three-dimensional concepts, such as the cylinder, sphere and cone which the old masters studied so carefully.

These simple elements may be joined to make further combinations. A schema may be like the little rolls of plasticene which children join together to make dolls and model animals. But any model or picture that has been memorised can serve as a schema, no matter how simple or complicated

Play-Doh Compound 2012

Simple volumes are made and joined. This is very much like the way in which schemata in drawings are made and joined.

As Gombrich explained, the schema is “the first approximate, loose category which is gradually tightened to fit the form it is to reproduce.” Accurate depiction can come about only when the artist goes on to correct and revise the schema.

Page 10 from Successful Drawing 1951

These basic volumes may be combined to represent all solid objects. The classical volumes are the cylinder, sphere and cone – which have curved surfaces. To these Loomis added the cuboid and the pyramid – which have flat surfaces.

LINE GREATLY ELABORATED

We saw in the previous chapter how complex drawings may be developed from the simplest of beginnings, the primordial circle.

Representational drawing and painting are developments of the same thought-process. Observations are recorded using lines, along with their extensions: brushstrokes and patches of colour. The result is a construction which is in some ways equivalent to the scene, but at the same time is quite distinct from it, just as the child’s drawing is equivalent to a head, but is quite distinct from a real head.

At left: Seated Female Nude

Kupferstichkabinett Berlin

At right: Susanna and the Elders – detail (1647)

Gemäldegalerie, Berlin

Showing how an elaborate painting was based on comparatively simple lines

In these pictures by Rembrandt we can see how the idea of the head and figure were first given with lines, and how these lines were developed with increasing complexity – as tone and colour were added.

However, even the developed painting shows its origins: its linear basis may still be discerned. The painting is closer to a photograph than a drawing is, but the painting still shows that it has been constructed from separate elements and thoughts.

REPRESENTING RATHER THAN COPYING

The Dance (The Happy Marriage ?VI: The Country Dance) c.1745 detail – reversed

In this oil sketch, Hogarth further developed the ideas which started with his thumbnail sketches.

Analysis of Beauty, plate 2, 1753 (detail)

A full elaboration of the thumbnail notes which Hogarth had made on the spot.

Analysis of Beauty, plate 2, 1753 (detail)

The brief notes of each figure which Hogarth used as the basis for the engraving above.

These are the sort of notes which Hogarth is said to have made on his thumbnail while observing a pair of boxers – hence the term, ‘thumbnail sketch’.

The art historian, E H Gombrich (1909 – 2001), introduced the word ‘schema’ when explaining how representations develop. A schema is a basic unit which might serve as a representation. So the rough circle that a child draws to represent a head might be called a schema. The child might introduce other schemata, such as lines to represent hair, or dots to represent eyes. The more sophisticated the artist the more he or she can add to his or her vocabulary, with each new schema being a combination of the simpler schemata used earlier on.

Gombrich showed how, in earlier centuries, this process of developing and memorising schemata had formed an essential part of the training of an artist. So called ‘copy-books’ provided ready-made schemata for pupils to copy and memorise. Few of these books remain because, Gombrich suggested, they were used so frequently that they wore out and were thrown away.

In the example above, Hogarth used the simplest of means to represent a scene of dancers. He noted the movement of each dancer with only one or two lines, to be developed later from his vast store of knowledge. In the Renaissance much more elaborate schemata were employed, as they still are by many illustrators. There is a complete range of complexity. At one end of the scale are the schemata of the pure French Impressionist, like Monet: little more than patches of colour. At the other end of the scale are the complex schemata of a Baroque artist, like Rubens (who had memorised a vast repertoire including whole figures and landscapes drawn from memory).

HOGARTH’S PLAN TO LEARN A VISUAL VOCABULARY

Hogarth wrote about his approach:

Having in the beginning of life lost a great part of my time, in engraving coats of armes on Silver Plate, and being desirous of appearing in the more eligable light of an History Painter or engraver, but then considering the time it must of course in the ordinary way of study take me up [that] there would be left little or none to spare for the ordinary enjoyments of life unless a more expeditious method could be found for the atainment of what I aim’d at. It therefore put me upon considering what might be done in this case[.] as I was copying in the usual way and had learnt by practice to do it with tolerable exactness, which is the first thing necessary to be obtaind, it occur’d to me that there were many disadvantages attended continually copying Prints and Pictures altho they should be those of the best masters nay in even drawing after the life itself at academys.

For as the Eye is often taken off the original to draw a bit at a time, it is possible to know no more of the original when the drawing is finish’d than before it was begun. Thus it is common with the hackney writers to know no more of what they have been copying than if they had not wrote a line, unless they have paid attention to it with that design[.] it is true such attention may and often is carried on in copying in our way, but there is this difference what is wrote is what should be retaind as it may be word for word the same with the original whereas what is copied for example at an academy is not the truth, perhaps far from it, yet the performer is apt to retain his perform’d Idea instead of the original, more reasons I form’d to myself but [it is] not necessary [to give them] here[. I asked meyself ] why I should not continue copying objects but rather read the Language of them and if possible find a grammar to it and collect and retain a remembrance of what I saw by repeated observations only trying every now and then upon my canvas how far I was advanc’d by that means.

There can be no reasons assign’d why men of sense and real genious with strong inclinations to attain to the art of Painting should so often miscarry as they do [on the left page: and more that might be given why] but those gentilmen who have labour’d with the utmost assiduity abroad surrounded with the works of the great masters, and at home at academys for twenty years together without gaining the least ground, nay some have rather gon backwards in their study as their performance before they set out upon their travail and those done twenty years since will testifie. Whereas if I have acquired anything in my way it has been wholy obtain’d by Observation by which method be where I would with my Eyes open I could have been at my studys so that even my Pleasures became a part of them, and sweetned the pursuit.

As this was the Doctrin I preach’d as well as practic’d an arch Brother of the pencil gave it this turn That the only way to learn to draw well was never to draw at all.

William Hogarth (1697 – 1764)

From an unpublished draft of The Analysis of Beauty (1753)

The Mnemonic System.

Draft C, BL. Eg. MS. 3015, ff. 7-11

LEARNING OR NOT LEARNING FROM EXPERIENCE

Detail – Marriage A-la-Mode: 2, The Tête à Tête about 1743

This subject would be impossible to paint direct from life because a model would not be able to hold this pose for long enough. Even a photograph would look frozen by comparison. By combining elements of the language of painting – the forms and volumes he had memorised – Hogarth brought exceptional vigour and character to his depictions.

detail from a patternbook 1538

The young artist could copy and memorise these drawings, and so build up a large visual vocabulary.

Detail Reclining Nude 1974–6

Coldstream rejected the the egg-shaped volumes we saw in Raphael and Hogarth, and restricted himself to dots and dashes (often charming in decorative effect). This meant his pictures gave little sense of volume and movement.

Detail The Rape of the Sabine Women (c.1635-40)

Rather than restricting himself to dots and dashes, Rubens included in his vocabulary whole figures of great variety. This gave his pictures a powerful sense of volume and movement.

As we have seen on the previous page, Hogarth argued in favour of developing the memory, and did so with enormous power. He determined that he, “…should not continue copying objects but rather read the Language of them and if possible find a grammar to it…” Surely no-one would want to be one of those he warned against, who had wasted time copying ‘at academys for twenty years together’ only to find that they had ‘gon backwards’.

Hogarth was appealing to an earlier tradition, the one which had nurtured preceding artists – and had done so no matter whether they were talented or untalented. This tradition was based primarily on memory, on developing pre-conceptions. Just how seriously this training was taken may be seen by the number of copy-books which were published in the 16th and 17th centuries. In Art and Illusion Gombrich wrote about these books in a chapter called Formula and Experience. The young artist would copy the drawings presented on the pages of these books and learn to repeat them from memory.

As the memory drawing experts* of the 19th and early 20th centuries were to confirm, students who trained their memories this way became more perceptive, not less. These patternbooks were used so thoroughly that they became worn out. Few remain in existence. However, many artists have argued against this tradition. Rather than fill their minds with formulae and memories, their stated aim has been to look at the world totally without preconceptions. Rather than full minds, they have yearned for empty minds, or to see with “The Innocent Eye”.

* (such as Lecoq de Boisbaudran and Catterson-Smith).

But, as Gombrich explained throughout Art and Illusion, it is impossible to paint without a preconception of some sort, even if it is only of the most rudimentary kind – a single short line, for example. The preconception comes first, then the checking against life. This is just as true of small preconceptions (such as circles) as of large ones (such as whole figures). Artists who refuse to stock their minds with visual memories are continually returning to the beginning, to the simplest dots and dashes. It is impossible to gain maturity with experience, because the artists are determined not to learn.

Sir William Coldstream, for example, described this continual rejection of memory and experience. After painting freehand, as it were, for short periods, usually of much less than half an hour each, he would check again by measuring. “…the idea of making sure about the thing, within the limits of the game, it means a lot to me.”

Where Coldstream’s preconceptions would be severely limited in number, checked frequently against nature, Rubens’s preconceptions would include whole figures, costumes, landscapes and still-lifes. Clearly he, too, would check against nature, his portraits, for example, are intensely individual, but his visual vocabulary was vast compared with that of Coldstream.

Self-portrait

Rubens’s grasp of a very large visual vocabulary by no means impeded his ability to make strikingly individual portraits.

BEGINNINGS: THE EXPERIENCED EYE

Page 6 of Art and Illusion by E.H.Gombrich (1909 – 2001)

Even the most sophisticated representation (such as the dog by Velázquez) depends on the same mental process that had intrigued Gombrich when he was a child.

I well remember that the power and magic of image making was first revealed to me, not by Velazquez, but by a simple drawing game I found in my primer. A little rhyme explained how you could first draw a circle to represent a loaf of bread (for loaves were round in my native Vienna); a curve added on top would turn the loaf into a shopping bag; two little squiggles on its handle would make it shrink into a purse; and now by adding a tail, here was a cat. What intrigued me, as I learned the trick, was the power of metamorphosis: the tail destroyed the purse and created the cat; you cannot see the one without obliterating the other. Far as we are from completely understanding this process, how can we hope to approach Velazquez?

E. H. Gombrich, Art and Illusion (1960), page 6

Each step provides a stereotype: for a loaf; a bag; a purse and a cat. These stereotypes may be varied as needed. For example, the cat could be made fatter or thinner, whiskers could be added, the tail could be made bushier. In this way, a stereotype, or schema, may be adjusted to conform to something imagined, or something observed in real life. The resulting drawing could then be employed as a new schema, and that, too, could be modified as required. This type of large visual vocabulary has formed the basis for most drawing and painting throughout history.

detail Philip IV hunting Wild Boar probably 1632-7

An extremely sophisticated representation, combining a sense of volume and movement with an indication of the fall of light. Separated brushstrokes do not show every detail, but direct the viewer’s imagination.

Gombrich’s primer demonstrated the accumulation of parts to make a cat. This painting by Velasquez demonstrates a similar accumulation of schemata, but far more elaborate.

REDUCING SCHEMATA TO THE MINIMUM

The previous pages have been about how schemata may be developed from the simplest to the most complex. This section is about the opposite approach, reducing schemata to the minimum possible.

detail: Girl Reflecting 1976-7

A result of applying the method described

by Francis Hoyland (below).

Stereotypes are kept to the absolute minimum.

Drawing a face, step-by-step. Alive to Paint, 1967 page 33

The previous page showed examples of the traditional approach to drawing and painting, the progression from simple shapes to more elaborate ones. In contrast, there stands the ‘Camberwell Easy’ approach – so-called (humorously) because it is simple in principle, but difficult in practice.

The face is indicated by a few lines – a very restricted schema. Often the artist does not even draw an initial schema, but keeps it in mind only. The artist may start with a little cross to indicate the limit of an imagined schema, a line to represent the extent of an eye for example.

Some theorists believe that this reducing of the visual vocabulary to an absolute minimum confers an artistic benefit. It forces the artist to make a new observation for each mark he or she draws. There is no opportunity to draw shapes from memory. This severe constraint is believed automatically to ensure that the drawing will be fresh and original. (As shown below, Degas thought the opposite).

In Alive to Paint, 1967, the artist Francis Hoyland (1930 – ) recalled a lesson he received as a student at Camberwell School of Art in about 1946.

One of the staff, I think it was William Coldstream, accused me of being imprecise and gave me a lesson.

The next time the model rested I turned to one of my friends for further explanation. ‘Every time you start painting,’ he said, ‘fix one particular proportion, say the width of an eye; then measure out from this first proportion. All other places are deducible from it, either as multiples of it, or as fractions of it. Hold your brush out like a spirit-level to find points that are horizontal to something on your series of fixed points, and make yourself a plumb-line so that you can find places that are below or above them.’

Francis Hoyland. Alive to Paint (1967)

Portrait of Patrick George, 1952

A conscientious application of the ‘Camberwell Easy’ approach to observation.

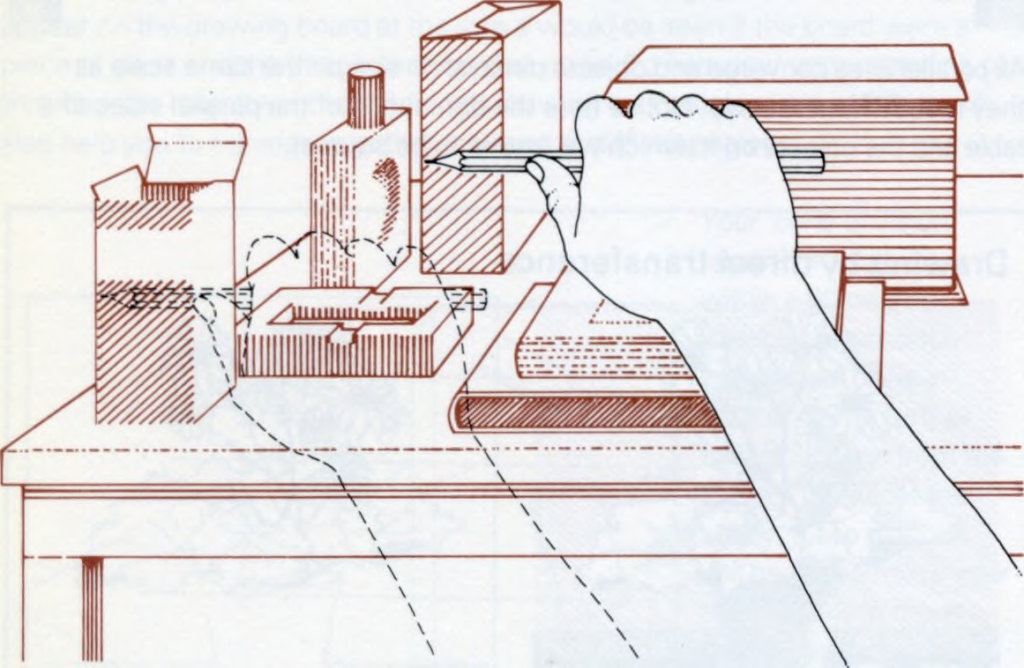

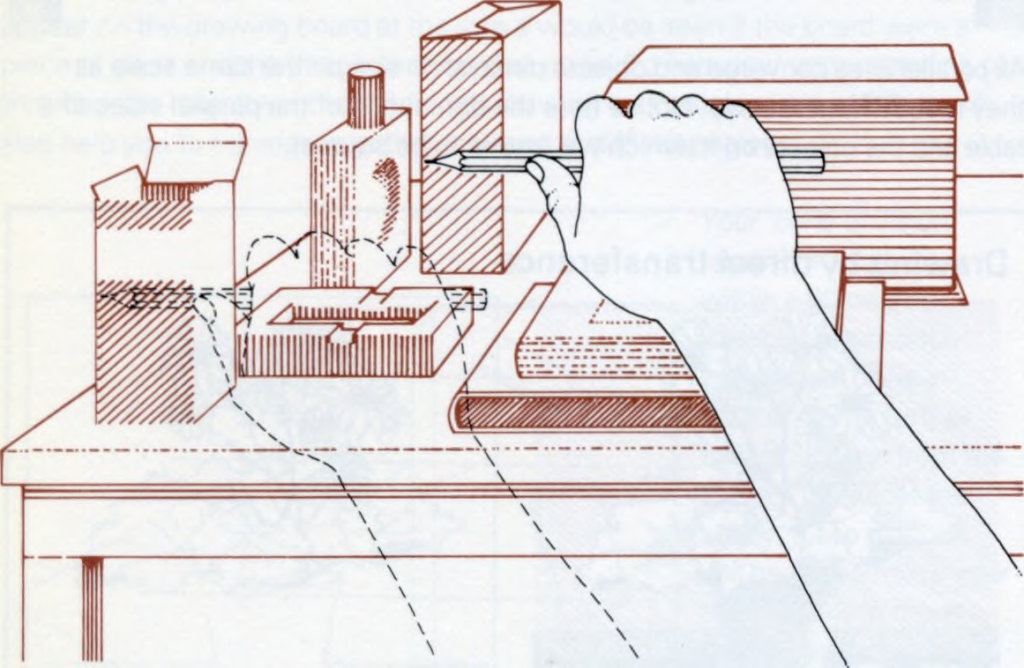

MEASURING

The following diagrams describe methods by which artists can ensure that their delineations are accurate.

They are from:

The Simon and Schuster Pocket Guide to Drawing,

Diana Armfield (Ed) (1982), pages 40 and 41

If you train your eye to see accurately you will gradually become accustomed to judging proportion and scale and the relation of one thing to another in a composition. There are devices that will help you to check the lines that you draw and these can be useful, but try to rely first on your own observation and use these methods only as a means of double checking. It can be surprising to discover how the mind tends to read objects of a similar size as occupying the same dimensions irrespective of the distance between them. By measuring with a unit of comparison that is closer to your eye you will begin to find out about perspective and foreshortening.

Measuring with a pencil

Hold the pencil upright in your hand, steadied by the thumb and gripped firmly by the fingers. When measuring verticals the thumb should be uppermost, for horizontals the hand is held level. The arm must be fully outstretched so that comparisons are constant. A ruler or piece of card marked with the units you want to compare can also be used.

Find an edge that you want to measure in comparison to another line that appears to be a similar length. Line up one end of the pencil with an edge of the near object and mark the other edge with your thumb. Now move your hand, keeping your thumb still and compare the length marked by the pencil with the further object (holding it at arm’s length). This method will work only within the range of your cone of vision since your arm acts as a pivot from your shoulder and describes the arc of a circle. Measurements made at the extremes of this limit would not relate to the flat surface of the drawing. Begin by measuring regular-sided objects; the contours of rounded objects are more elusive.

Measuring angles

Difficult angles can be measured easily by holding the edge of a piece of paper against one side of an angle and folding the paper to follow the line of the other side of the angle. The paper can then be laid on your drawing or held just above it and the angle checked since it has brought it into the same plane as the drawing.

Using imaginary clock hands

Another way of judging angles, though relying more on judgement than on practical shortcuts, is by imagining the hands of a clock superimposed on the angle. This will reduce the scale and bring it into a closer plane.

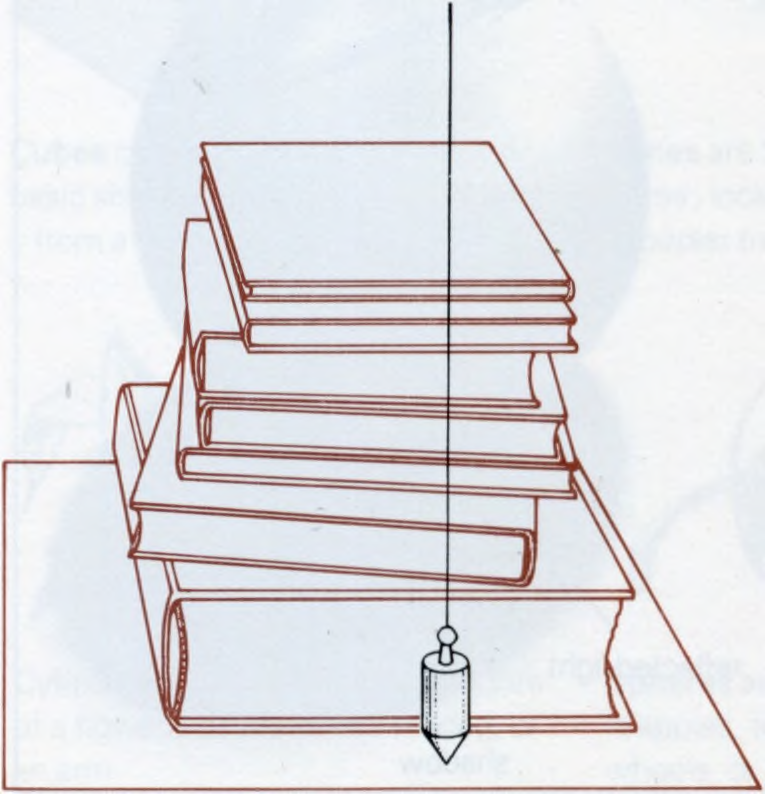

Measuring with a plumb line

A plumb line is a useful and accurate way of checking verticals and spotting what lies vertically beneath them. It is particularly useful in drawing the figure and in helping to determine the main axis of the body. A plumb line will correct any bias of vision that your eye may have in judging the position of the vertical (this can often be a surprising discovery). It will also relate parts of your drawing, from the back to the front plane. A plumb line is easy to make (follow the directions given below).

A plumb line can be made by tying a small lead weight (a fishing weight, a tube of paint or even a bunch of keys) to a piece of string, or more ideally fishing line. The weight should be just heavy enough to keep the cord taut. Hold the plumb line out in front of you and regard it as a portable grid to check the edges of objects and line up things that appear to lie above or below each other.

_______________________________________

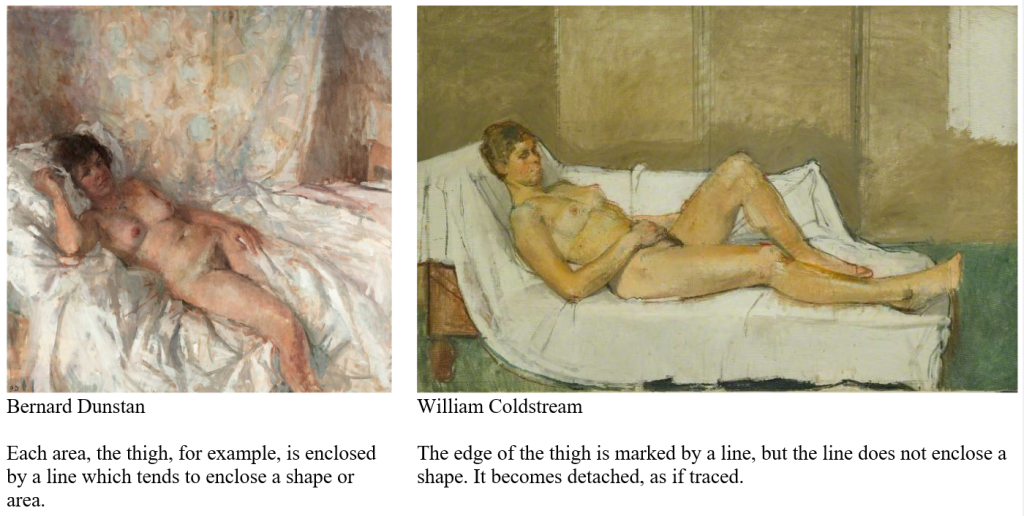

DRAWING APPROACHES CONTRASTED

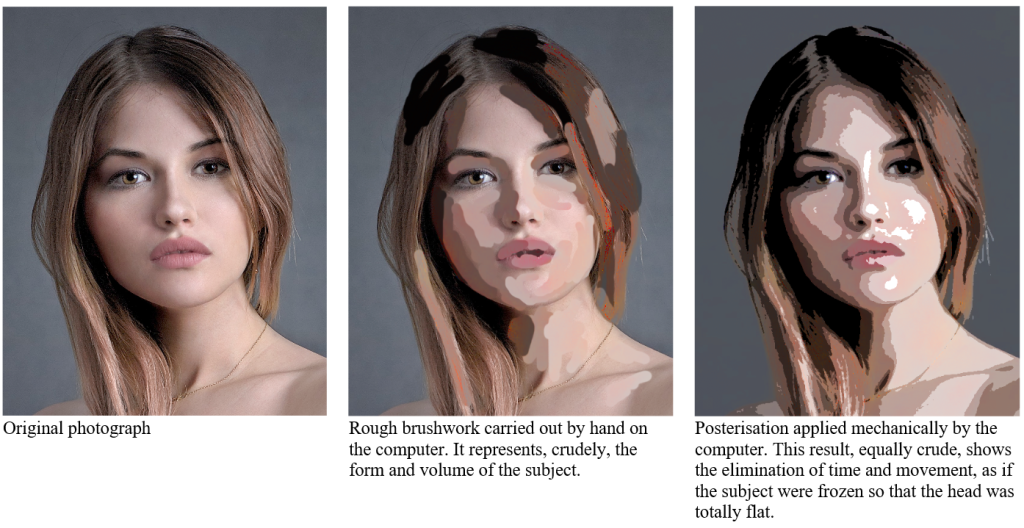

Here two approaches to constructing a drawing are compared. The first, starting with an oval to represent a head, exemplifies the normal approach, used more or less for as long as people have been painting pictures. The artist begins with an oval, similar to the primordial circle of the child, and develops the drawing as a modification of that oval. The second approach is an attempt to break away from this standardised method as far as possible. The artist seeks to observe with the utmost freshness, keeping ‘pre-conceived ideas’ (such as the oval) to the minimum possible. . The illustrations below show how the different approaches may be applied to the same subject, in this case a photograph by Jerzy Górecki from Pixabay.

The method came to prominence at an art school set up in the Euston Road in London (1937-39), so is often referred to as the ‘Euston Road’ approach. William Coldstream was a prominent member of the school, and he took the approach to Camberwell art school when he went on to teach there (hence the name ‘Camberwell Easy’ by which the approach was known for a while. Coldstream then went on to become the head of the Slade school, where this approach then became dominant.

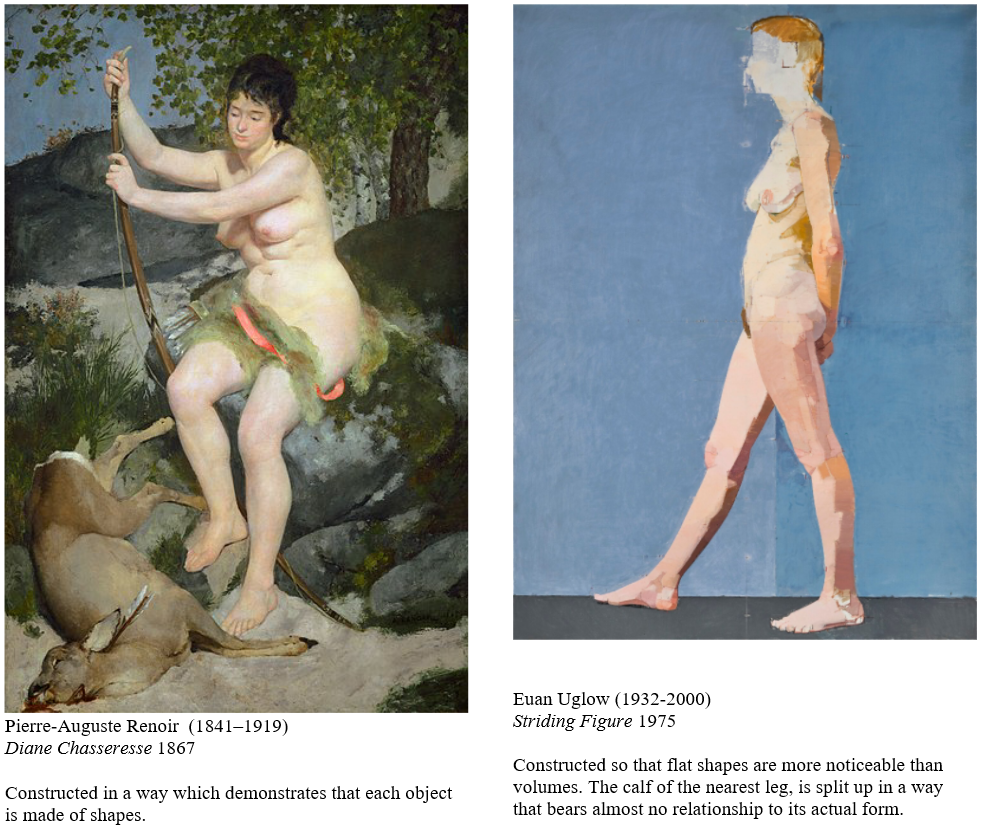

AUGUSTUS JOHN AND WILLIAM COLDSTREAM COMPARED

Most artists starts by drawing the head as an egg-like volume, or sometimes a box-like volume; but some artists are afraid that, if they were to adopt that approach, they might find themselves repeating a formulae for drawing a head, rather than observing the subject in front of them.

As we have seen, the Euston Road method was devised in order to overcome this problem. It is an exaggerated means by which to ensure that the artist cannot simply repeat a standard drawing from memory. The method allegedly forces an artist to observe freshly. The drawing starts with an estimate – in the case of the drawing on the previous page, an estimate for the width of the eye. (Any notable part of the subject could form such a basic unit. The eye here is only an example). Once this has been drawn, the proportions of every part of the rest of the drawing depend on this single unit. If the model moves, these measurements no longer apply.

The model, the picture plane and even the artist’s eye have to be rigidly fixed in place in order to ensure an accurate tracing.

Fellow students of mine at the Royal Academy Schools, keen followers of Coldstream, used to set up similarly elaborate contraptions.

The model has to return to the original position exactly, or else the drawing become impossible to complete. Even changing the position of the artist’s eye by an inch or so can upset the measurements. Some artists set up viewing points so that they can always return to the exact viewing position. In both approaches, the artist starts with the intention of representing a head, so both artists begin with a conception: an expectation of what a head looks like. The Euston Road follower is less likely to start with a bold oval, but nevertheless there is a conception of the head of some sort, or else there would be nothing to measure.

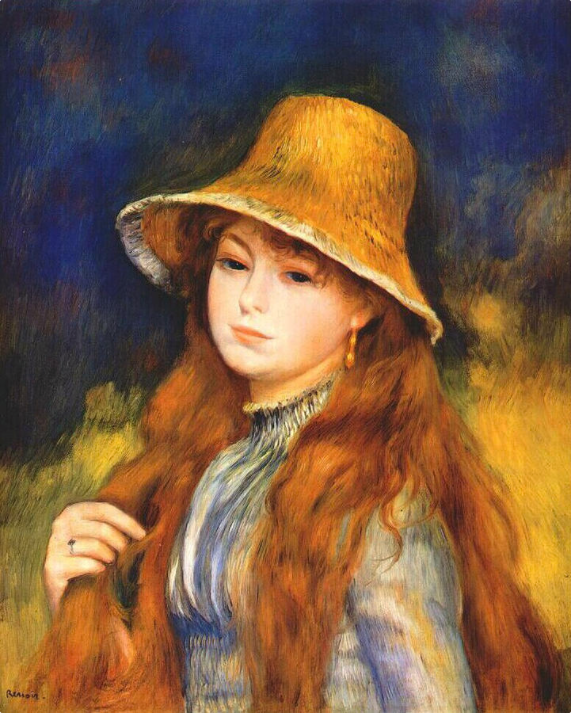

The normal approach involves time and movement, because the volumes of the subject become more apparent as the subject and the artist move. (Renoir used to encourage his models to move while he was painting them). The Euston Road approach eliminates the time and movement element as much as possible. The artist and subject are as static as possible. The artist observes from one point in space, with only one eye – at least while taking measurements. This approach is known as a monocular (one-eyed) approach, in contrast to the normal method, the binocular (two-eyed) approach. The binocular artist is more aware of volume because of the three-dimensional awareness that comes with using both eyes. But, arguably, the movement of the model and of the artist are even more important factors than the use of two eyes in providing a sense of three dimensions.

Girl in Straw Hat 1884. Oil on canvas, 55 x 47 cm. Private collection

According to his son, Jean, Renoir used to encourage his models to move (presumably within limits). This would have made the volumes of his subject more noticeable. This is borne out by his superb handling of volume.

Artists who use the normal approach are not drastically impeded by the loss of an eye: a one-eyed artist can be just as aware of form and movement as a two-eyed artist – if viewing a slightly moving subject. For example, there is no difference in character between the drawings Sir Alfred Munnings made before and after he lost an eye.

So the Euston Road method consists of an exaggeration of what has always been part of the art of drawing – checking proportions and checking balance with a plumb line (either real or imagined). But whereas a normal artist may come with a repertoire of forms, from the simple primordial circle of the child to the immense visual vocabulary of an artist like William Hogarth; the Euston Road follower rejects the idea of introducing memorised elements, and has to start each drawing just like a beginner, with only the tiniest element to begin with – the single line.

The approaches shown here illustrate the difference between:

1. drawing with preconceptions, whether limited like the child’s, or sophisticated like those of advanced artists and

2. drawing by limiting preconceptions to the fewest possible, more limited in fact than the child’s.

One cannot escape from thinking in terms of schemata of some sort, even if they are reduced to the minimum possible, such as a single line depicting the width of an eye. Drawing without preconceptions is impossible.

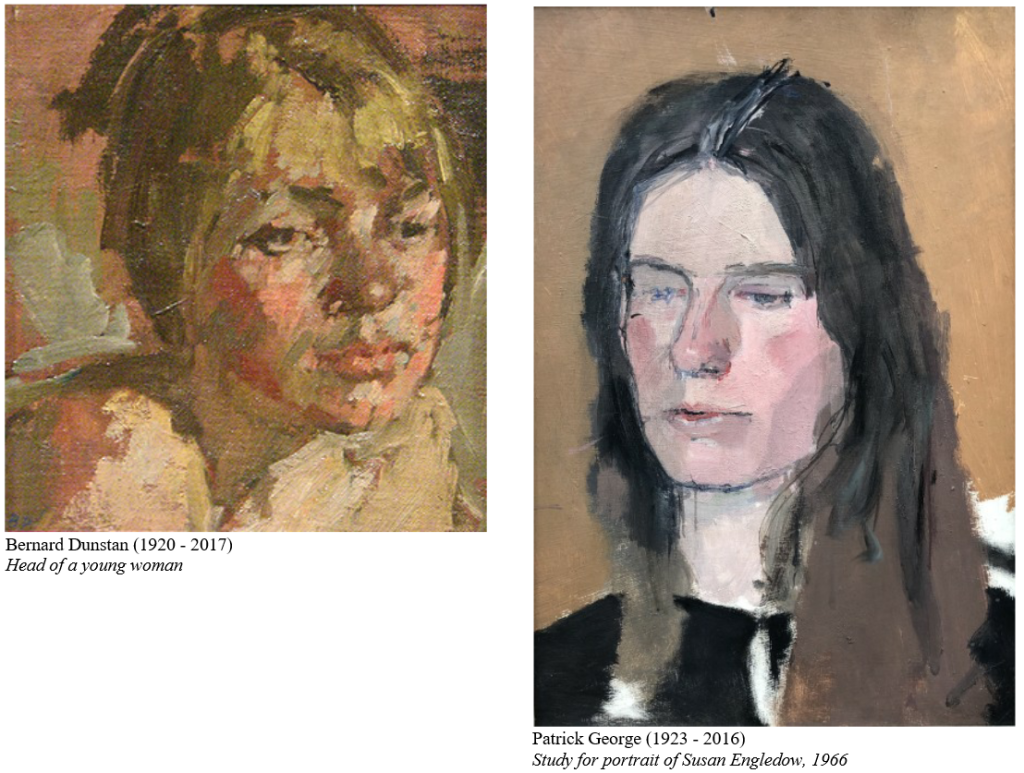

APPROACHES TO MOVEMENT

Here are two paintings, both arguably unfinished, or at least in a sketchy state. The approaches to representation have much in common as far as observing colour is concerned, and both are realistic rather than abstract or grossly distorted.

However the approach to drawing is quite different: in the Dunstan the lines are made by brushstrokes which surround shapes rather as the original schema of the child’s drawing, though more sophisticated.

In contrast, in the George, the brushstrokes do not sweep around the head. The shapes are traced bit by bit, and even points of measurement are marked where the lines change direction. The lines come to resemble a head only as a by-product of accurate tracing. The head is treated not as as a volume which moves in space, but is reduced to a static series of flat shapes.

DEGAS ON THE MEMORY

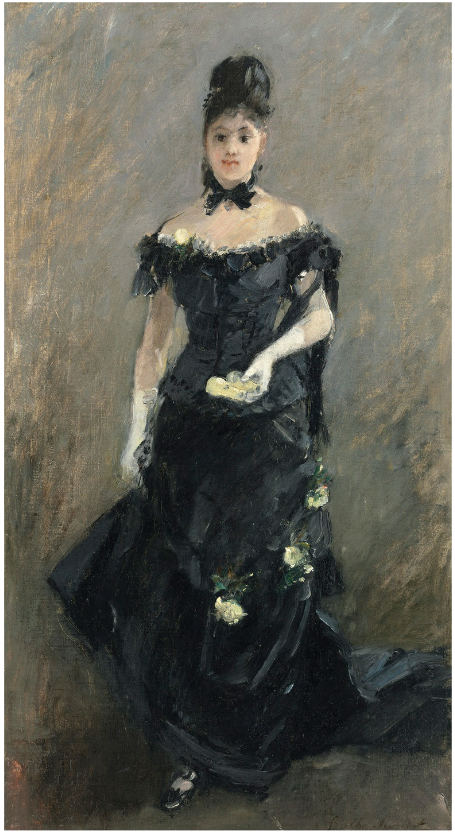

Here are examples of the work of the artists mentioned by Degas, followed by his comments.

Sir Thomas Elyot 1532-33

This drawing would tell a sculptor where to put his or her fingers when modelling a clay bust. A tracing of a viewfinder would not be so informative.

The Third Siege of Missolonghi 1825-6

Delacroix’s sweeping lines are just as informative as those of Holbein, but are more suggestive of physical movement.

Femme en noir 1875

This shows what an accomplished painter Morisot was herself, and well equipped to understand what Degas had to say.

Dancers c1880

This image depends on the artist’s memory.

None of these poses could have been kept for more than half a second by the dancers, nor would a photograph have provided enough detail of the hands and feet (even though Degas was a keen amateur photographer).

The painting is an example of Degas’s exceptional ability to recall and to reconstruct a figure from his knowledge.

Degas had said “that the study of nature was of little significance, painting being a conventional art, and that it was infinitely more worth-while to learn to draw after Holbein.”

Berthe Morisot, as quoted in

DEGAS, DANSE, DESSIN by Paul Valery

Librairie GaIlimard, Paris, 1938

“It is all very well to copy what you see; it is much better to draw what you only see in memory. There is a transformation during which the imagination works in conjunction with the memory. You only put down what made an impression on you, that is to say the essential. Then your memory and your invention are freed from the dominating influence of nature. That is why pictures made by a man with a trained memory who knows thoroughly both the masters and his own craft are almost always remarkable works; for instance Delacroix.”

Degas, quoted in:

SOUVENIRS SUR DEGAS by Georges Jeanniot

La Revue Universelle,

15 October and 15 November, 1933, Paris